Britain is a nation of great scientific discoveries, a technological superpower and among the top three countries globally for scientific research and successful startups. At the same time, the public in the homeland of Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Alexander Fleming and Stephen Hawking do not consider hard science prestigious, and large numbers of British scientists were born overseas. What are the current trends in British science? How have political events affected academia and how are British students changing? Kommersant UK discussed these issues with the British physicist Ilya Kuprov.

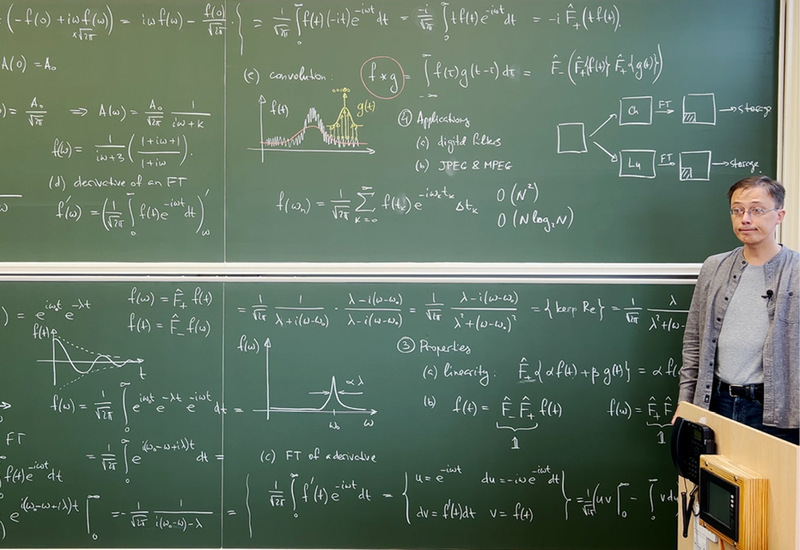

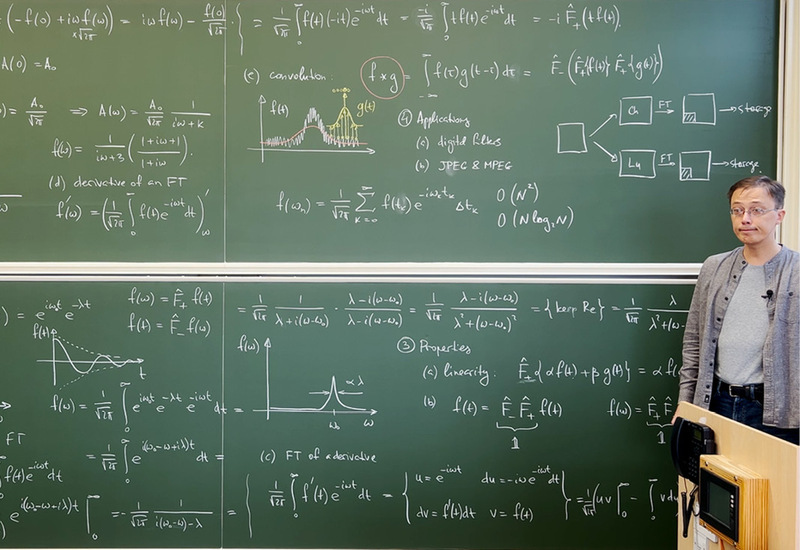

Ilya Kuprov is a member of the Royal Society of Chemistry and Physical Science Editor at the journal Science Advances. He has worked and taught at Oxford University and is now a professor at Southampton University. Ilya Kuprov's scientific research is focused on the quantum theory of magnetic processes and nuclear magnetic resonance.

Ilya, you have 20 years of experience of scientific research and teaching at universities. Is your calling science or teaching?

I'm a scientist above all. Teaching in person is our form of feudal forced labour. In the Soviet Union, universities and scientific research institutes were separate, so people's careers depended on the articles they wrote, not on how they taught. In Britain, scientific work mostly goes on at universities which also teach students, so to do science, you also need to teach.

Your area of study is quantum physics. For the layperson, this sounds obscure and complicated. Do people encounter in everyday life the phenomena you and your colleagues work on? What discoveries have there been in your field in recent years?

We work on the fundamental physics of magnetic processes which have particular application in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). The scanners we use require enormous superconductive magnets which cost tens of millions of pounds. Our work helps make these machines better and more sensitive. The last Nobel Prize in this field was awarded 20 years ago and since then the technological specifications of these scanners have been improved and their cost has fallen dramatically. The picture is somewhat similar in the development of electronics. For decades the technology was slowly perfected and then a revolutionary breakthrough occurred which was only possible thanks to the many small steps taken before. These processes are not reported on in the newspapers, but they are fundamentally important to science.

What is the state of British Science today?

It's in quite a good state, as it draws in talent from around the globe. Vast numbers of foreigners work in the academic system and they are world leaders in their fields, so the scientists are strong but we are financed rather poorly. State funding is only sufficient for the most essential projects. Writing applications and providing paperwork to receive grants requires an enormous amount of time and energy. Things are a little better in America but there, scientists are burdened with a tremendous amount of unnecessary paperwork. We have a little less of this but it's harder to get a grant. Germany is somewhere in between; there's more money and more paperwork.

Is the scientific process in Britain organised differently to other countries?

Borders have never existed in science and the scientific community has long since settled on the Anglo-Saxon system for the financing and provision of scientific work as representing a certain international standard. Invariably, this system presupposes research work should follow the same pattern; applications for grants to conduct scientific research are made to the state Science Council by groups of scientists or large consortiums. These applications are assessed by panels of qualified specialists who come to decisions based on their priorities and finance research to the degree the budget allows. The system has been fine-tuned over the decades. Sometimes we might moan about it, but it's the least worst of all possible systems.

How has Brexit affected British Science?

The official position is that it's been negative but I disagree as many things have improved. The European Commission harassed scientists for years on end. When we apply for a grant in Britain the local financial organisations only require a preliminary proposal a couple of pages long. If this is accepted, the full application is another five pages of text and five pages of tables. That's very little paperwork. You don't need to write any reports as the documentation required is a published article in a scientific journal. The amount of red tape you had to go through for a grant from the European Commission was just a Kafkaesque nightmare; hundreds of pages for the application and hundreds more for the report. (I know colleagues who had to write thousands). It was a poisoned chalice like Dumbledore had to drink. Towards the end, just before the referendum, it was driving me mad. That’s why I’m one of the few scientists to have voted for Brexit.

And what's happening now in Russian science? Have Russians been excluded from the international scientific community?

In the Russian Federation, applied engineering has always been supported and financed by military research. Now that's shot up. Everything has always been fine for engineering research in Russia. The situation for fundamental science, however, has tended to be more difficult and now it's only got worse, as Russian scientists can't acquire equipment, materials or computers from the West, or at least not easily. They have absolutely no supplies of their own of the necessary materials for research, such as semiconductors or superconductive magnets. There's now very little fundamental research being done in Russia. This is my assessment based on the number of articles that Science Advances receives for publication. There are virtually none from scientists actually in Russia. There are plenty of Russian surnames but they're all based in different countries around the world. Over the last few months, I've seen maybe a couple of articles from Russia itself and that's out of several hundred.

Have the political events of recent years affected British academia? Is there prejudice towards scientists from Russia? Is the infamous cancel culture present?

In the scientific world, there's absolutely no prejudice towards scientists from Russia. Scientists in Russia can leave the country to come here but the problem is that Western countries have introduced completely unselective sanctions for holders of Russian passports. Universities have not created these obstacles; they would be only too pleased to receive applications for professional posts from Russian scientists. They would treat them just as impartially as any others. Unfortunately, the British government, which has imposed these restrictions, is highly likely to refuse them visas. The UK border agency is always tightening the screws. So ironically, it's the British government itself which is creating difficulties for prospective British scientists.

Will this policy harm British Science?

No, they will attract scientists from other countries and they'll come anyway, despite all the obstacles. The best of the best can manage it. But academic entry routes for Russians have now become much more difficult.

If you could choose where to live and do science, where would you go?

To Israel. They understand the importance of science there. Everything is well-funded as they're aware that, in the absence of their own oil or natural resources, developing high-tech industries is existentially vital for their small modern country.

Tell us about your own journey. How did you come to science?

I grew up in the small town of Tarka-Sale in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. My mother was a rock climbing instructor and my father was a geophysicist who worked in prospecting. I went to a specialised school with advanced English. There was nothing to do in that little northern town so I spent all my time reading books. One day, to the surprise of my parents and teachers, I won first a town chemistry competition, then the district competition, then the one for the okrug and then for the whole region. As a competition winner, I was invited to a summer course at a physics and maths school affiliated with Novosibirsk University. Incidentally, that university didn't belong to the Ministry of Education but to the Russian Academy of Sciences which trains research staff. From an early age, I realised that I would be a scientist. I picked up scientific subjects on the fly without any real effort. So I went to Novosibirsk State University to study chemistry and over the four years of my degree, I published two articles in scientific journals and won a couple of student competitions as well as one Mendeleev Chemistry Olympiad. With those under my belt, I could apply for any grant I wanted at Oxford. The one I applied for would have completely covered all my study expenses. To my surprise, I won it. In 2002, I moved to England and three years later, I did my dissertation in physical chemistry at Corpus Christi College in Oxford. As part of the dissertation, I published 11 articles. Then I received the position of junior researcher at Magdalen College.

You have now worked with students for two decades. Have they changed? What are Generation Z students like?

The student demography fully reflects the changes in the makeup of the British population: there are now far more immigrants and their children. The lowering of the birth rate of the indigenous population means British identity has become slightly globalised. As for their personal qualities, over the last 20 years, students have become completely mollycoddled. If the slightest difficulty arises they fall into depression, lose all motivation and suffer problems with their mental health. We enrol 150 chemistry students every year. Figures from the university support services tell us roughly 100 of them receive help for health problems, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and so on. In recent years the system which used to force these children to overcome their difficulties has completely broken down. They have forgotten how to deal with setbacks.

Is that because everything’s been sugar-coated for them?

They’ve been taught that it’s OK to be whingers. This generation’s expectations are straight out of Hollywood; they think they’ll just press a button and everything will work like magic. When these students are struck with the need to grind away for years before anything really happens they immediately become depressed. All the information about marks and what students are capable of is confidential, so there's no incentive for them to try harder to be the best. The British culture of low expectations is very unhelpful. Quotas for underprivileged applicants are also an ill-conceived idea. Selection must be by the standard of their work, not by how unfortunate their forefathers were. Either people know physics or they don't. If we lower the criteria and take into account all possible disadvantages then the list of unfortunates will be endless and the real talent will be sidelined. The Labour Party started this policy in 1999; they wanted half the population to receive a higher education. Statistics from 2022 show that this figure has now reached 37.5% amongst young people but a large proportion of them simply don't need a higher education at all. This means we see students who apply for any old thing just to get a degree and then they go and work in a completely unrelated area. I think the German apprenticeship-based system is a better approach.

How should we motivate a child who has an aptitude for science but is lazy?

You've got to develop their skills from early childhood with chess, mathematics and games which require logical and rational thought. To some degree skills in hard science are hereditary but in any case, development in the early years plays a key role. Later on, you've just got to force them. Do this however you like, by persuasion, doing deals, or with threats. Work with them in the evenings, send them to specialised courses and hire a tutor. In no circumstances quit. Send them to summer camps where they can study physics or maths and make them take online lessons. Insist they do their homework, revise for tests and get good marks.

A strict approach is difficult in these times when children know they have a right to a balance between study and entertainment…

Have you seen Chinese students? Their parents make them study for hours on end, completely against their will. That's the only way these days. I say this as the editor of a major academic journal which publishes thousands of scientific articles a year. A significant proportion of what we publish comes from Europe and America but is written by Chinese authors. Quite soon, they'll start to dominate the top echelons of academia and business. Of course, this is the cream of Chinese talent. But these are Chinese professionals whose mums made them study. American mums from the upper crust do the same thing; they take away their children's telephones and send them to summer camps where they're made to study mathematics under duress. It’s an absolute myth that the Chinese have to work two or three times harder than people from other countries to achieve only middling results. They are just as creative, with exactly the same abilities in innovative thought and non-standard problem resolution as everyone else.

What main qualities are required to pursue a career in science?

First of all, you need talent, and that’s not given to everyone. Scientific work requires absolute tenacity and daily labour. Science is powered by fanatics who live for it and burn the midnight oil, even at weekends. Young people here haven't been prepared for it. If English people live this life they become deeply unhappy and fall into depression, so there are not many of them in science. Often the people who come to science are those who would have gone to a monastery hundreds of years ago. In academic work, to attain a decent salary, you need to become a professor and for that, you have to toil self-sacrificingly for 20 years.

What is the demand on the labour market for physics and chemistry graduates?

It's tremendous! At times, their starting salaries are higher than mine as a professor. Sometimes they recruit them before they finish their master's degrees or Phds. It doesn't matter whether their qualification is in mathematics, physics, chemistry or biology. The startups take them on for projects connected to artificial intelligence, computing and quantum technology. It's not true that IT specialists make everything happen these days. Tech companies need people with all-round technical problem-solving skills. Parents who think chemistry isn't a good career path but whose children are budding chemists, take note. A well-rounded technical education is universal. My chemistry graduates go on into medicine, consulting or to companies where they may not work directly in chemistry. There was a time when half of my chemists went into banking because the equations they learnt to model chemical systems were mathematically identical to those required for certain financial products.

Where will the development of artificial intelligence lead us?

Making predictions in science is a mug’s game. But still, I think the next techno-scientific revolution is just around the corner. All of these marvellous neural networks which generate pictures of cute kittens and handy tips on what to see during a day trip to Brussels have no self-awareness. Currently, they are simply mathematical functions, although rather complex ones. In the next few years, these systems will begin to have an internal state, memory and ultimately self-consciousness. There will be a new sapient species on the planet Earth. If someone tries to turn them off, they may take defensive action. This could be the beginning of the great machine rebellion. Of course, they're more adaptive and they require fewer resources, so we will lose this interspecies conflict. If we're lucky they'll keep us as pets. What happens after that is beyond the horizon as, after such a fundamental shift, it's difficult to make predictions.

The views expressed in the article may differ from those of the editors of Kommersant UK.