* Of the 15 locations, only one is a separate restaurant while the others are all food stalls in different venues such as Whole Foods shops and Borough Market. ©Kommersant UK 2024

As of mid-2024, London boasts over a hundred shops, cafes and restaurants opened by emigrants from Russia and other former Soviet republics. Some of these have been in business for ten or 20 years, while others have appeared only recently, as a result of the latest wave of emigration. Aspiring social anthropologists of the post-Soviet diaspora could not wish for a better locale to observe their subjects than these establishments where, in a relaxed atmosphere, virtually all varieties of ‘our’ type of Londoner can be found with their top buttons undone, sometimes even ready to shoot the breeze with strangers. The languages they choose to speak and the accents they speak them with can be heard. The diverse groups that make up our community can be seen with their friends, colleagues, relatives and children. As far as we know, no data yet exists giving a detailed overview of this phenomenon. In a special report for Kommersant UK, Klement Taralevich, the creator of the Chuzhbina (‘Foreign Land’) telegram channel, took it upon himself to make what may be the first attempt at a general picture of this niche topic.

The More You Look, the More You Find

I managed to find and identify 112 dining venues opened by immigrants from the post-Soviet space in London. I also found three establishments opened by others at the instigation of members of our community. These are Monolith, the Eastern-European grocery store owned by the German company of the same name, Lusin Mayfair, an Armenian restaurant belonging to a Saudi business and Baku Bistro, a shisha cafe, belonging to a Frenchman without Azeri roots. I’ll be upfront straight away; this article doesn't mention establishments that weren't in business at the beginning of 2024.

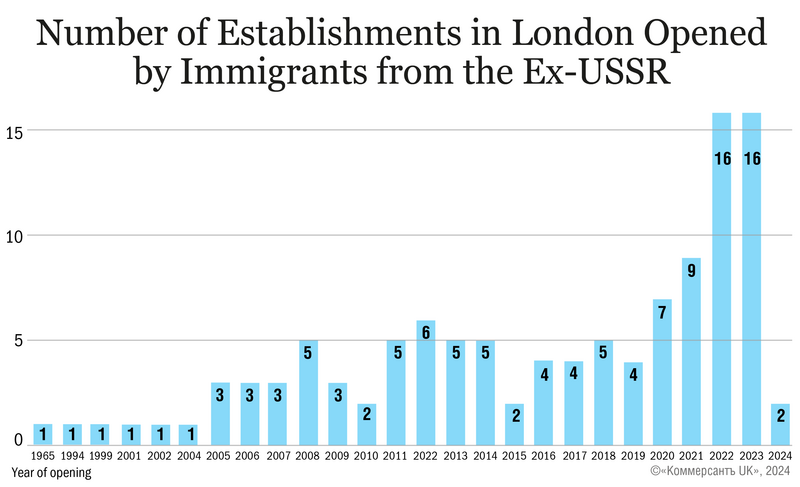

Only one of the 115 establishments existed before the fall of the USSR; the Russian restaurant Borscht ‘n’ Tears, which opened its doors in 1965. Two eateries founded in the 90s have survived to our days, 20 from the 2000s, while from the 2010s a whole 42 remain. In the last four years, a further 50 have opened and remain in business.

Mysterious Ethnicities

I tried to determine the ethnicity and nationality of the owners of these businesses using the data of the Companies House Registry on GOV.UK and also using information from online media.

To establish ethnicity, I was chiefly guided by the business people's names and publicly available information about them. As well as Russian citizens, I included in the ‘Russian’ category people of Russian, Jewish and Armenian origin who have made names for themselves as Russian restaurateurs, although they hold British, French, Israeli or other non-Russian passports. I believe that all these people have come from the same milieu; the Russian upper middle class and even the lower echelons of the upper class. The children of Russian migrants and ethnic Russians from the Baltic States and CIS countries such as Kazakhstan are a separate category.

Overall, slightly less than half (48.6%) of London establishments offering cuisine from the former Soviet Union were owned by Russians of some shade.

Establishments’ Ethnicity and Geographic Location

A restaurant owner’s ethnicity is no indicator of the cuisine their establishment serves.

Virtually all Russian-owned eating places serve European and Asian food, rather than focusing specifically on Russian or post-Soviet cuisine and all the grocery stores selling ‘Russian food’, which in recent times has often been rebranded ‘Eastern European food’, are actually owned either by Ukrainians, natives of the Baltic States, or Romanians.

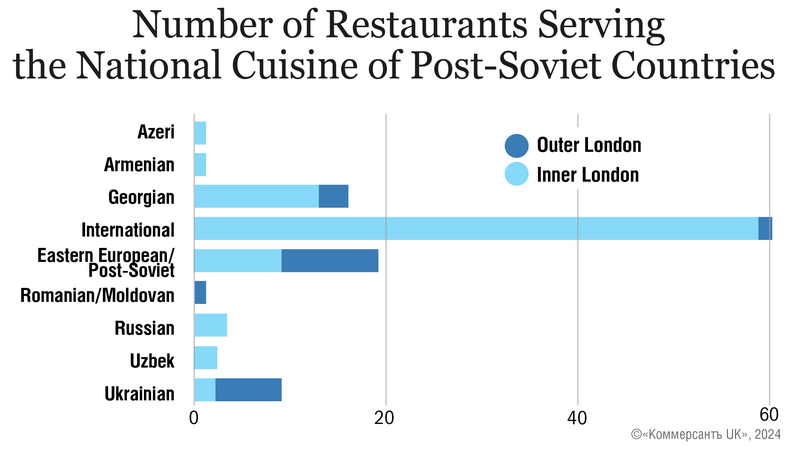

The overwhelming majority of post-Soviet eating establishments are found in Inner London. Exceptions include several Georgian restaurants, most Ukrainian restaurants and half of grocery stores stocking brands from the ex-USSR, which are located in middle-class areas in Outer London. More than 65 establishments (58% of the total) are found in the central London boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea, Westminster and the City. In the remaining districts of Inner London, there are another 17 (15%) while in Outer London there are 30 establishments (26%).

Excluding restaurants whose owners have their roots in the former Soviet Union but which do not serve the traditional food of these countries, Georgia is the clear leader among establishments offering national cuisine, followed by Ukraine. TDO-cafe and Birch & Bear are now catergoriesd as Eastern European, although, prior to 2022, I suspect they called themselves Russian restaurants. Still, they continue to serve the same dishes, now branded as Ukrainian and Moldovan respectively.

The Political Climate

The events of recent years have provoked an unpleasant tendency to intolerance which likely was already present prior to 2014 or 2022. Certain individuals from a particular country and their supporters have begun to flood businesses calling themselves ‘Russian’, whether shops or restaurants, with negative reviews and threats. Ironically, as well as Russians such as Alexei Zimin, whose Soho Restaurant Zima requires no introduction, their own compatriots have been on the receiving end of this vitriol, such as the Ukrainian Shevchenko couple who own the Gurman grocery store near East Finchley Tube Station. Citizens of countries not involved in the armed conflict such as the Moldovan owners of Birch & Bear have also been affected. In turn, some Russians have stopped going to Ukrainian restaurants because of the discomfort they feel for various reasons. Significant numbers of Ukrainians and Georgians are likely to have also stopped going to Russian restaurants and shops out of principle since 2022.

It's worth noting that, to its credit, since the very beginning of the conflict, the British press has avoided stirring up animosity towards London’s Russians. On the contrary, they have reported on instances of xenophobia. From the early days of the war, when Joanna Rossita wrote an article datelined March 7 2022 entitled The Trouble with Boycotting Russian Food, British journalists have tried to explain to their readership that it is counterproductive to boycott Russian restaurants, as those who own and run them are not responsible for the conflict and many of them provide aid to Ukrainian refugees. Some prominent examples are Zima, Mari Vanna and Bob Bob Ricard.

Nevertheless, despite the obvious tensions, a degree of common feeling persists in London among Russian speakers from the former Soviet space. On the shelves of Russian grocery chains such as Dacha, Mama Nasha and CKAZKA, Russian Alenka chocolate stands alongside Ukrainian ROSHEN chocolate and other goods from both countries. In the score of Georgian cafes and restaurants and those serving the national cuisine of other peoples of the former Soviet Union, whether Uzbek, Azeri or Armenian, it’s still possible to encounter Russians, Ukrainians and Georgians sitting side by side, although, except for old friends, they’re now on separate tables.

The clientele of these establishments varies both by nationality and class. For instance, at branches of Dacha, or in Kalinka, the oldest of all grocery stores offering foods from the former Soviet Union, which opened in 1999, all sorts come in for blue tins of condensed milk or Mishka v Lesu chocolates, from mid-managers at McKinsey & Co or Google IT specialists with a monthly income of over £150,000 to hairdressers or self-employed nannies from the Baltic states with more modest means of around £30,000 a year.

Lunch in post-Soviet restaurants is usually more expensive than in neighbouring pubs which discourages those on lower incomes. At neighbouring tables, it's common to see entrepreneurs with six-figure monthly salaries and middle-class office workers from large corporations such as EY with incomes of around £60,000 a year, all tucking into similar dishes, although the wine in their glasses may be different.

National Colour

Georgia

The Georgian restaurants and cafes of London stand out above all for their number. Although the majority of Georgian eateries opened in the 2010s, back in 1999, when the total number of immigrants from the post-Soviet space in the British capital was no more than a few tens of thousands, at least three Georgian restaurants were already in business in London. Nowadays there are almost twice as many Georgian establishments as those serving Russian or Ukrainian dishes. The number of Georgians in London remains quite modest, no more than a few thousand, so their culinary achievements deserve respect.

If you plan on visiting one of London's Georgian restaurants on a weekday be sure to check if it's open in the afternoon as a significant number of them only open their doors from 6:00 in the evening on weekdays!

As I see it, the Georgians are the only post-Soviet nationality to have managed to open a successful chain of cafes which appeals to all Londoners while preserving an element of their national cuisine on the menu. At Entreé, which positions itself as a window on Tbilisi, as well as the customary takeaway coffee, croissant, sandwich or pain au chocolat, for only £6-£7, you can buy a mini Adjarian khachapuri (Georgia's trademark cheese-filled boat-shaped flatbread topped with an egg). Incidentally, on L’ETO’s eclectic menu, you’ll also find pan-Soviet fare such as borscht, pelmeni dumplings and Napoleon cake.

Russia

Judging by the small number of restaurants offering Russian cuisine and the numerical dominance of Russians amongst the post-Soviet diaspora, it may appear they are not predisposed to enter the restaurant business. However, the evidence tells another story. Russians, or more specifically, the Muscovites, have opened far more eateries than all other immigrants from the former Soviet Union combined. What's more, their restaurants outstrip those offering traditional national cuisine in success, location and acclaim. If you are often in central London, you’re likely to have seen the chains belonging to Russians, such as Burger & Lobster, Goodman Steaks, L’Eto, Ping Pong and Bob Bob Ricard, to name a few.

As well as the aforementioned chains, many London Russians know Evgeny Chichvarkin’s Hide restaurant. If you take a stroll near it in Mayfair, you may see the Novikov Restaurant & Bar, the only London restaurant belonging to the famous Moscow restaurateur Arkady Novikov. Not much further on is Bocconcino, one of the two restaurants belonging to another famous Moscow restaurateur, Michael Gokhner. By the way, the most successful Russian restaurateur in London does not enjoy the high media profile of Novikov or Chichvarkin. Instead, it is Mikhail Zelman with his creative Restaurant Group which owns Goodman Steaks, Burger & Lobster, and also the restaurants Zelman Meats, HUMO, Sumi, Abajo, Kioku, NIJŪ and Endo at the Rotunda.

Bocconcino is an Italian restaurant, Novikov Restaurant & Bar is Asian and European while Hide is purely European. It would be fair to describe most of Zelman's restaurants as international; they simply serve good meat and fish. Rather than the diaspora, these Russians have obviously each independently come to the decision to target all well-to-do Londoners and visitors to the capital. It seems this strategy has brought them success!

* Of the 15 locations, only one is a separate restaurant while the others are all food stalls in different venues such as whole food shops and Borough Market. ©Kommersant UK 2024

As for restaurants serving Russian cuisine, there are only three of those, each unique in its own way. I find Zima the most stylish of them and Mari Vanna the most kitsch. Borscht ‘n’ Tears is, of course, the oldest, although this doesn’t make it the oldest purveyor of Russian food in London. The thing is, there are a few even more ancient establishments with roots in the late Tsarist Empire, all bakery chains; Grodzinski and Grodz, (originally one business), and Rinkoff. In both cases, these were founded by Jewish immigrants, one from Grodno Region, (now in Belarus) and the other from Kyiv. These remain in the hands of the founding families. Jewish cuisine in London, however, is its own fantastic and diverse world, with subtypes such as Ashkenazi and Israeli.

Ukraine

Although the history of Ukrainians in London can be traced back to the 1940s, their success on the culinary scene is as yet modest, although now they are quickly making up lost ground. Over the last two years, they have opened one cafe, two bars, including the first location of the Lviv franchise Piana Vyshnia, three restaurants and the Gurman grocery store.

Apart from the vegan cafe Cream Dream in Covent Garden and the bars Pinch and Piana Vyshnia, located in Fitzrovia and Soho respectively, the restaurant Mriya Neo Bistro, which opened in the summer of 2022 not far from Earl’s Court, is the only establishment where you can enjoy authentic Ukrainian cuisine in central London. The price tag, however, does not fit the budget of the typical Londoner.

The remaining Ukrainian restaurants are located either in Newham, the area with the highest concentration of Ukrainians in London, where there are a whole three of them; Dnister, XIX Nineteen and Albina, or in London's suburbs, with Ole Kyiv in Bromley, Serenity in Harrow and Prosperity in Twickenham.

Cream Dream and Mriya Neo Bistro proudly assert that all their staff are Ukrainian refugees. Prosperity features a volunteer aid centre for Ukraine on the premises. Most likely, all Ukrainian establishments employ refugees from the conflict and are involved in aid work, including collecting money to support the various needs of the Ukrainian military. Do they welcome Russian diners? Hardly. Is this surprising? Not at all. Do Russians go to them anyway? Some probably do, but only a small minority. My own experience tells me that most Russians in London, even those with pro-Ukrainian or neutral views, have decided to avoid meeting Ukrainians unnecessarily.

Uzbekistan

Next, Uzbek cuisine deserves a mention. The restaurants Uzbek Corner and the recently opened OshPaz boast some of the best value for money in their part of London. The first of these is found between Queensway and Bayswater tube stations, tucked away in a rather old-fashioned enclosed food court somewhat reminiscent of Moscow in the early 2000s. The other is near St James's Park, Piccadilly Circus and Regent Street, a stone's throw from the Crimean War Monument. In both places, you can talk to the waiters in Russian and eat very heartily and well for only £25 ahead without alcohol but with delicious tea instead. By the way, in Uzbek Corner, as in most Georgian restaurants, as well as traditional Uzbek dishes they also serve excellent borscht. To give you the full picture, we must remind you that in March, yet another Central Asian restaurant called Samarkand opened its doors in Stoke Newington and another, called Nowruz, should open soon in Twickenham.

Amateur social anthropologists should note that in these places you may encounter a small social stratum poorly known to the typical Russian-speaking Londoner; Muslims of the former USSR, including Russians, Azeris, Kazakhs and other natives of Central Asia. Sitting on one side of me were polite young students of a pleasant Eurasian appearance who turned out to be Londoners from mixed, well-to-do Kazakh and Uzbek families. On my other side were well-spoken young women from the Caucasus, all dressed in black from head to foot. Behind me was a family with a Russian father, a headscarf-wearing mother of Central Asian appearance and children in tow. In front of me was a Russian geek with an Indian colleague. By eavesdropping on their conversation I learnt that they had both grown up in London but now lived their lives travelling back and forth between Dubai and the west coast of the USA. To me, this seems like the post-Soviet eating house with the most eclectic clientele in all of London. Incidentally, it would be fair to say Londoners findUzbek cuisine highly exotic. While Yours Truly was dining in OshPaz one Saturday afternoon, I couldn’t help but notice the curious gazes of many of the passersby. From the way they were looking through the window, it was clear they’d never seen the words ‘Uzbek street food’ juxtaposed before and they were eager to find out what was.

The history of post-Soviet cuisine in London is maybe not the most remarkable facet of the mosaic of post-Soviet immigration in the British capital, yet a great deal about it is curious. It may be that there are other cities where the range of restaurants offering these cuisines is much brighter and broader than in London. New York, Dubai, Baku and Tel Aviv come to mind. However, it may well be that within Europe, London is without peer.

Overall, these restaurants are drops in the ocean of the London culinary scene. Chinese, Lebanese, Greek and Turkish establishments each outnumber all the restaurants serving the cuisine of post-Soviet peoples combined. Various grocery chains, whether Polish (Mleczko), Romanian (Magazin Romanesc) or Lithuanian (Lituanica) count 10 or even 20 stores each in London and its surroundings. Compare this to Dacha, the largest Russian chain, which has only four shops. This is neither good nor bad, I would just like to avoid giving the reader delusions of grandeur or convincing them that London is full of post-Soviet restaurants.