Pregnancy is one of the most important periods in a woman’s life. These nine months, full of emotions, hopes and entirely justifiable concerns, are always a path to the unknown. At this time, all women are especially vulnerable, both physically and emotionally, especially if it’s their first time (although, during subsequent pregnancies, women develop a better understanding of how easily something can go wrong and so may feel no less stressed). If a future mother is in a foreign country and doesn’t know the local ways of preparing to bring a baby into the world, then she has even more cause to feel concerned. Kommersant UK has prepared a detailed guide to birth and pregnancy in Britain to help any of our readers who find themselves in this situation.

In this first article, we discuss pregnancy; the following articles will address birth and parenthood.

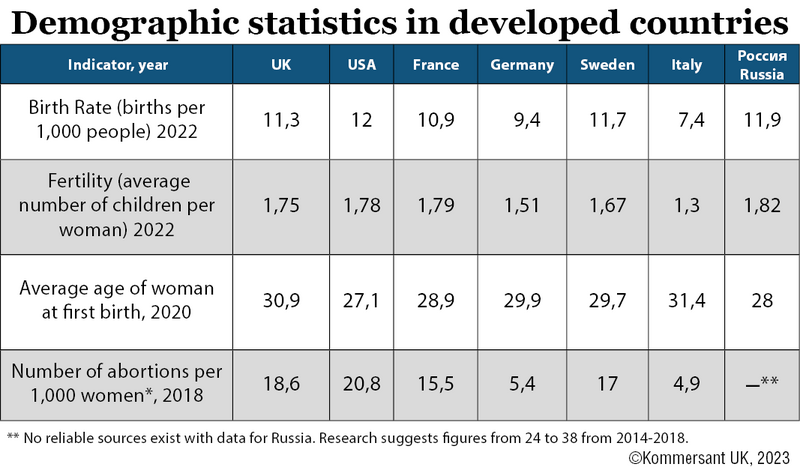

Pregnancy in Britain in figures

During pregnancy, family planning and medical services in Britain are provided by the NHS, which means that they are free for women residing here legally. Nine out of ten newborns in Britain come into the world in the maternity wards of ordinary hospitals, while slightly more than two per cent see the light of day at home. Only four per cent of births take place in private maternity homes or private wards in public hospitals (the remaining four per cent includes births in midwifery centres and elsewhere).

624,828 births were registered in 2022, which is 11.3 babies for every 1,000 inhabitants. This is 0.5% less than the previous year (over the past ten years, the birth rate has slowly but unwaveringly declined).

As in most developed countries, in Britain, the age of the average mother is rising; women generally have their first baby at the age of 30 (the average age of new fathers is 33). The trend for children to be born outside of marriage is also increasing; in 2021 for the first time, most children were born outside of marriage or a long-term relationship (51.3%).

In recent years, a third of babies born in England and Wales have had one or both parents born outside of Britain (34.2% in 2021).

Amongst pregnant women as a whole, the risk of pre-eclampsia (a condition causing high blood pressure and other symptoms which poses a threat both to the mother and the foetus) is assessed to be from five to eight per cent. Girls below the age of 18 and women over 35 are judged to be at greater risk. Mothers over the age of 35 are also at greater risk of giving birth to babies with Down syndrome and other genetic disorders, as well as of having stillbirths or miscarriages. However, in all age groups, most pregnancies go smoothly, with only around eight per cent accompanied by complications potentially affecting the health of the mother or child. This context, in which intervention is often unnecessary, guides obstetric practice in Britain.

Foreign women on short-term visas pay non-resident tariffs for all consultations.

What is different here

The maternity care system here is based on the postulate that pregnancy is not an illness, but rather, a natural condition for women at a certain stage of their lives. This is why there are no weekly visits to medical institutions or endless tests. It may be this that surprises women raised in the Former Soviet Union most of all. At times they may feel under-examined.

This means that a woman may go through her whole pregnancy without visiting an obstetrician or gynaecologist. In fact, throughout a normal pregnancy, a woman may only have a handful of tests (in particular, vaginal ultrasound tests are not usually conducted). Any tests that are carried out are not done by a doctor, but by a midwife. Midwifery services in Britain fulfil a function similar to women's health clinics in Post-Soviet health systems. In the UK, having an appointment with a gynaecologist is a sign that there might be something wrong.

In Britain, there is no concept of hospitalisation “to preserve the pregnancy”. Spontaneous miscarriages during the first eight to ten weeks are considered a natural evolution in the body’s process of rejecting an unhealthy embryo (medical data suggests that slightly more than a quarter of all miscarriages fall into this category) so it is only worth going to a doctor after having several miscarriages in a row.

Here, pregnant women a little over 30 are not called “old first-time-mothers” and they are not automatically prescribed caesarean-sections. The decision to operate depends on the specifics of the case, as happens for women with a history of previous caesarean births, in the same way as decisions are taken on whether to operate in cases of myopia (short-sightedness) or varicose veins.

In Britain, pregnant women’s decisions are treated with respect; if you don’t want to do a test for Down Syndrome, you’d rather not know the sex of your child or if you are against the vaccination of newborns, that’s your own business. The rules state that no one should be pressured into taking a decision, although, in practice, talk of the possible consequences of certain courses of action is sometimes used to frighten women into following advice. Equally, no one looks judgingly at women who come to do abortions. What’s more, at their first appointments, pregnant women are usually delicately asked if they actually want to go through with the pregnancy and whether they are ready to assume the role of mother.

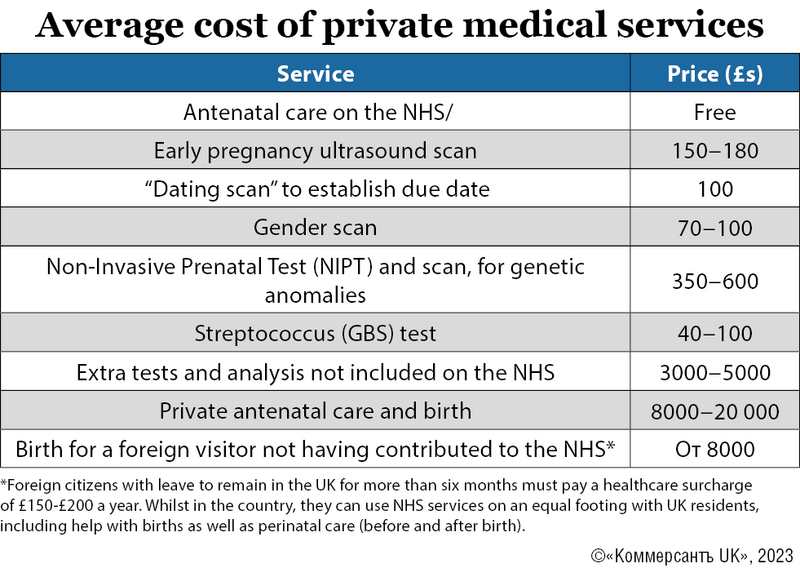

A pregnancy may cost a woman or couple tens of thousands of pounds, or nothing at all. In both cases, the medical personnel providing treatment may be the same. Women don’t need to spend a penny on medicine as, from the moment they begin antenatal care to the child’s first birthday, they have the right to free dental care and medicine from the NHS.

Medical insurance usually does not cover pregnancy or birth, it may only be applicable to medical appointments made on referral from a GP.

But the main difference which makes Britain stand out is encountered right at the start; sex education.

Being safe is being prepared

The social planning of sexual life is taken seriously in the country; from the age of eight, school children receive lessons in PHSE (Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education), which includes the fundamentals of sex education. On becoming a teenager, school children may, on demand, receive free contraception (including condoms, “planned” and emergency contraceptives). Girls below the age of 16 may receive abortions without their parents being informed (although they will be strongly recommended to tell a family member). Contraceptives in this country are free, from The Pill to patches or coils. All of this is dealt with by Sexual and Reproductive Health, or “GUM” (Genito-Urinary Medicine) clinics, which are part of the NHS. The location of your nearest clinic can be found by making a postcode search on the NHS site. Women may go to these for a range of reasons connected to their sex lives; for advice, to do tests for STDs, receive treatment for them and to terminate pregnancies. The victims of sexual violence can receive help. Abortions are also free in the county and are carried out by the NHS. To arrange one, you must see your GP or contact a family planning clinic. After seeing a nurse at the clinic, a pregnancy can be terminated using tablets until the tenth week. Up to the 24th week, a surgical procedure can be arranged at the clinic.

Treating infertility

If a long-awaited pregnancy doesn’t come, you can contact your GP or planned parenting clinic to receive a consultation and do a hormone test. If a couple has fertility problems, it’s possible to receive a referral for IVF, or In Vitro Fertilisation, This procedure is available on the NHS to women up to the age of 43, however, it must be approved by the local Integrated Care Board (ICB). If done privately, the cost of one cycle of IVF starts at £5,000.

Surrogacy is legal in the country, but not provided by the NHS. The full cost of this process starts at £50,000 (this includes payment of the surrogate mother who will bear the child, as well as the cost of IVF, consultations and legal services).

Those two fateful lines

In Britain, perinatal observation is carried out by сommunity midwives. Several years ago, on the confirmation of a pregnancy, a woman first went to see their family doctor or GP, who would refer them to a midwife’s practice. Now it is easier to go to the Community Midwifery Service directly; they can access entire medical histories and assess potential risks. If necessary, they can refer women to a specialist. It is only necessary to go to the GP for general medical problems.

Antenatal care usually begins as soon as a test comes up with those two lines confirming the pregnancy. ‘If you do it late, the midwives will wonder why; maybe her husband locked her up at home and didn’t let her out, or she was hiding from her mum or the social workers’ recounts Natalia Kolesnikova, a midwife at the South London Community Midwifery Service. ‘It always raises questions about mental health, family problems or whether the child is wanted. Of course, everything can be explained by irregular periods… but it’s better to do things on time’.

In the course of a normal first pregnancy, a woman attends ten appointments (during subsequent pregnancies, it’s seven to eight). At the first appointment, at eight to ten weeks, the future mother is asked about her medical history, her lifestyle and that of her partner. Blood samples are taken for extensive testing, including for haemophilia, anaemia, HIV, syphilis etc. The woman gives information about her diet, vitamin and folic acid intakes. They are given booklets with health advice and a “pregnancy book”, or “maternity notes”, where all the information related to the pregnancy must be recorded, including the results of tests and examinations, the history of appointments and complaints during pregnancy and a birth plan put together by the woman herself.

At routine appointments, the midwife measures the woman’s blood pressure and stomach size, listens to the baby’s heartbeat and asks about the child’s movements. If a pregnant woman has any doubts, or she feels that her condition has worsened, she can either call her midwife or a hospital hotline. At appointments in hospitals, two ultrasound scans are made; during the 12th week (a “dating scan” to confirm the due date) and at the 20th (to check the child’s physical health). Also, several blood tests are done, including assessment of the risk of the development of genetic problems such as Down, Patau and Edwards syndromes. By the second ultrasound scan, it is already possible to determine the sex of the baby, but the sonographer is not obliged to do this. The human factor comes into play; according to the regulations, if the child is judged to be a hazardous pose, the medical worker is within their rights to focus on this and not waste time determining the sex, despite the importance of this information for the future parents.

During a first pregnancy, a woman is offered a place on a course for future parents, which it’s customary to attend together with the child’s future father. The course consists of several two-hour-long sessions, during which midwives give useful practical information about what women should take with them to the maternity home, how to prepare for a birth, the right way to breathe, and what is important for a mother and baby to do during the first days. In practice, between a third and a half of future mothers attend these courses. Many affirm that they turned out to be very useful, partly because they were able to meet other people in the same situation. These courses are organised in local areas, so they can help women to find companions for strolling and playing.

Unforeseen events

The rules guiding check-ups during pregnancy in Britain are quite strict, and if test results or perceived foetal activity deviate from the norm, the woman is immediately put on observation and is referred to specialists or consultants, who prescribe additional appointments and testing.

Even in the current economic situation, the NHS midwifery service readily assigns funding to extra check-ups and testing. ‘A huge breakthrough at the NHS has been the very informative, but expensive, NIPT test (known as the “Harmony Test). This identifies chromosome defects. It is prescribed even if risk indicators are only medium, as well as to all future mothers over 35’ notes Olga Gudko, going on her own experience of giving birth to four children. ‘This test is very precise and it gives you confidence, which you need if you're either preparing to become a mother for the very first time, the results of previous tests have been borderline, or if you’re not very convinced about the British approach to childbirth’.

For increased reassurance, many tests can be done privately, such as extensive blood tests, staphylococcus tests (on the NHS, this test is used selectively), or ultrasounds to determine the sex of the child. But note that the results of privately conducted tests are not automatically made available to the NHS. To ensure that medics have access to them, midwives advise that the data should be added to the woman’s Maternity Notes.

Maternity leave English-style

British law guarantees pregnant women the right to free antenatal care, protection from discrimination, maternity leave, and payments both during pregnancy and upon giving birth. Some of these regulations also apply to the father of the child, whether this is a husband, partner or supposed parent of a surrogate child.

Antenatal care provides a working woman with time off for visits to the midwife or doctor, as well as antenatal courses (the woman should receive her usual rate of pay for this time). A future father has the right to unpaid leave to attend two appointments, each with a duration of up to 6.5 hours.

After the woman has informed her employer of her pregnancy, the conditions of her contract cannot be changed and she cannot be dismissed. If her working conditions may be prejudicial to her health, such as if she needs to lift heavy objects or work excessively long hours, she should be offered an alternative position or reduced hours whilst keeping the same salary.

Maternity leave lasts for up to 52 weeks, and the woman may choose to take it from the 11th week until her supposed due date, or indeed continue her work until the final day of the pregnancy. If she feels unwell, leave begins automatically four weeks before the birth. If she has decided to skip maternity leave altogether, she is still obliged to stop work for at least two weeks after the birth (for factory workers, this is four weeks). The father of the child is also allotted up to a fortnight’s paternity leave after the birth. This leave may be taken in one go, or broken up into shorter periods within the first 56 days after the child’s birth.

There are two categories of maternity leave; ordinary (for the first 26 weeks) and additional (for the next 26 weeks). Mothers are only paid for 39 of these weeks. For the first six weeks, they receive 90% of their usual salary, and for the next 33 weeks at £172.48 a week. These payments are subject to tax. Fathers on paternity leave also receive £172.48 a week.

Pregnancy Care during the crisis at the NHS

Currently, the “crisis in the NHS” is spoken and written about with grim regularity, causing quite understandable concern amongst future parents about the state of healthcare provision. However, all the women we spoke to while preparing this article agreed that, however individual births turn out, overall, NHS provided care is delivered smoothly and calmly.

‘15 years ago, British medicine used to advocate making childbirth as natural as possible, but, since then, the trend has been to increase the amount of testing with the aim of reducing the risks for the mother and child’ notes Natalia Kolesnikova. ‘These days, they do ultrasounds more often during the third trimester, to see how the placenta is functioning. Forceps are used less often and quotas for the number of caesarean sections have been cancelled. On the other hand, I have to admit that the current trend to try to play it safe does lead to more artificial inductions of labour.

On comparing the Latvian and British systems, young mother Anna Dovgopolaya believes that the number of check-ups in Britain is just right, as in Post Soviet countries, there is too much control and needless testing. ‘Still, this light touch puts the responsibility on the couple who has decided to become parents’, says Anna. ‘So you’ve got to get ready beforehand and do tests to find any possible infections which might, unexpectedly, become the cause of some problems later on, such as lingering cystitis. This can be done for free at a Sex Health Centre, and your partner can come along too’. Also, Anna recommends not being shy to ask questions, doing your own research and asking for a second opinion if you have any doubts.

Mila Kuchma is the mother of five sons and a newborn daughter, all of whom came into the world in Britain. She believes that, since her first birth (14 years ago), the level of care for pregnant women has not declined, as everything is still done according to a clear plan. ‘I’m impressed by the English approach: everything happens the way the woman having the child plans it, rather than the doctor “birthing” as often happens in Post Soviet countries’, says Mila “It’s good that you can choose where to give birth: in an ordinary maternity ward, a midwifery unit, or in water. And you can change your decision at the last moment. This means women feel more relaxed, which reflects favourably on the process of giving birth’. She also considers it right that in Britain they take mental health very seriously, so she recommends treating the midwife’s questions as more than just a pointless formality: ‘In our traditions, stereotypes are very strong; everyone copes, and so should I. But if things are very hard, there’s no need for heroism. Don’t be afraid to talk about it, no one will report you to social services and take away the baby, but they might offer some help’.

Olga Gudko also notes that during her four difficult pregnancies, she never once felt there was a shortage of staff and, in critical situations, everything was done promptly. However, she advises pregnant women to pay attention to their health and take more initiative; ‘If you feel that something is wrong, be insistent, exaggerate symptoms, to get more attention from specialists’.

The next article will discuss births.