On 26 September, people gathered at London’s Pushkin House to meet someone present at the very dawn of Russian rock. Every Russian rock star from Boris Grebenshchikov to Billy Novik knew her name. Yet Natasha isn't a musician and has never even appeared on stage. She is a photographer who didn't just document concerts, but often also the private lives of rockers, many of whom became her close friends. Natasha has been living in Britain for 30 years now. In an exclusive interview with Kommersant UK, she told us how she managed to work with the Rolling Stones, marry a British banker and open her own publishing house all while keeping in touch with the stars of Russian rock.

How did your journey as a rock photographer begin? In the 70s and 80s, it seems music fans dreamt of getting up close to rock stars, as much to share their private lives as their creativity. Out of all the options, how did you come to choose photography as your profession?

I started to take photographs long before I realised that rock music existed in Russia. My mum gave me a Smena 8 camera for my 15th birthday. My dad wasn't a photographer but sometimes he took photos, developed them at home and dried them on newspapers laid out on the floor. When I was very small, I delighted in looking at Daddy's black and white photos with him on Sunday afternoons. “Here’s Mum, here’s Grandma, here’s your sister and here’s the cat”. It seems it kindled my interest in photography and then I got my first camera and I photographed everything I saw. I soon worked out that taking photographs helps you fit in better, whatever the company. Musicians often say “As soon as I picked up my guitar, all the chicks started fighting over me” and that's really what it's like. Something similar happened to me with my camera. When I had it, I started to feel more confident, even though I was terribly insecure; I wore glasses, my tooth stuck out and I had a fat bum which I was teased for. The camera helped me to deal with all that.

The sailors brought us rock music. I lived on Vasiliyevsky Island [in Saint Petersburg], right by the port. My friend had a brother who worked as a merchant seaman and he brought me a 45 of the Beatles in a sack of dirty laundry, that was in 1967 and I was 14 or 13. Diplomats also brought recordings. The father of another of my friends was the director of the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra. They went on tours abroad and secretly brought back recordings because they weren’t searched. Another friend’s dad brought reel-to-reel tapes. The start and end of them were French lessons, but in the middle, there were illicit recordings of things like Abbey Road. We listened to the music and we often knew the songs by heart, every note, but we didn't know their names. For a long time, we didn't even know what the performers looked like.

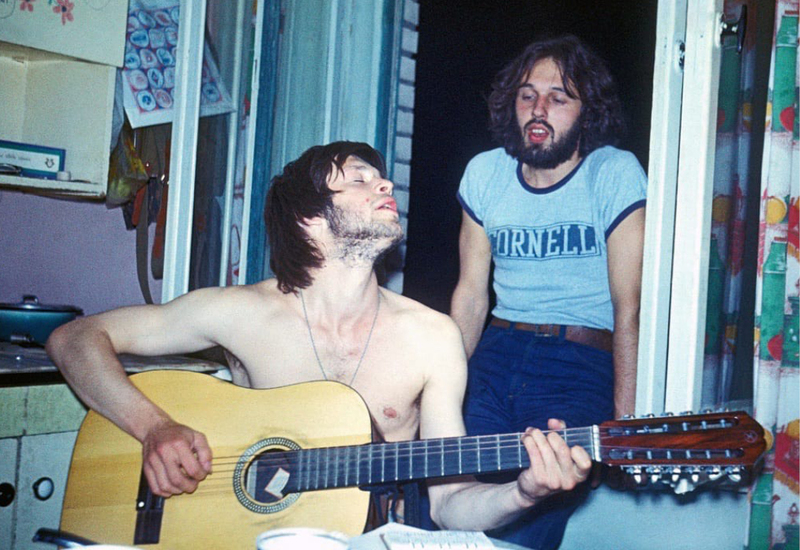

Later on, when I was 19, I started to study at a cultural institute and they sent us to a collective farm to dig carrots. We slept in icy beds. I couldn't resist lugging my record player there and I used to play Slade in the mornings. So our squalid Soviet barracks listened to very vibrant rock music. At the collective farm, I met a guy with a guitar who sang Beatles songs while sitting on some crates by the campfire. It was 1973, a time of stagnation and closed borders. They told us: “We live in the best country. The whole world hates us. America is preparing a nuclear bomb. English is the language of Enemy Number One”. In the Soviet Union, western music was a great rarity. Very few had even heard of the Beatles, but I had already listened to them, as well as the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and the opera Jesus Christ Superstar. 1973 was the golden age of Western rock music. Of course, I befriended that guitarist and when I returned to Piter [as St Petersburg is familiarly called] after the collective farm, he invited me to a practice session of the group it turned out he was in, called Big Iron Bell, which had splintered from another called Sankt-Peterburg. It was already cool in certain circles, although all of this was happening completely underground, the cops and the spooks didn't know about them. That session was the first time that I heard rock played live, in a cramped little room with drums, guitars and bass. I saw those dudes and my goodness, they had hair down to their shoulders... It was then that I realised what I had been born for.

I already had my camera, so I gradually started to take photographs; first the group at that session and then they introduced me to someone. We went to Tallinn together… After that, my husband, Sergei Vasiliev, was assigned to work as an electrician at the Almaz Marine Design Bureau on Vasiliyevsky Island. One of his colleagues there was Gena Zaitsev, a renowned hippie. Although he wasn't a musician himself, he was very active in the rock scene and we started to put on what they now call home concerts. We always had lots of guests. Grebenshchikov often came. I photographed him in the kitchen. That was just the beginning…

Could you tell us about your favourive photo shoots?

I enjoy working with people who understand what it's all about and like to be photographed. Viktor Tsoi and Grebenshchikov are striking examples. They never hid from the camera, they never took me for an invasive paparazza and they enjoyed being in the frame. I like it when people trust me, open their souls and we connect. Otherwise, it’s like a police mugshot; “Face the camera. Now look right”. It will resemble a portrait, but it won't have the spirit of the moment.

You have published a book about Tsoi. How did you learn to work with words and go from photography to biography? Can you tell us what Viktor was like and something about your personal relationship with him?

My mum was a linguist. All her life, she taught Spanish at the language faculty of Leningrad University and she knew six romance languages. Of course, there was an enormous amount of books in our house and my childhood was spent in a setting conducive to language learning. I already spoke French at the age of three, although I forgot it later on of course, and when I was five, my mother hired a tutor who taught me English. I got top marks for Russian and literature without ever really making an effort. I loved books and that's probably where my ability to lay out my ideas clearly on the page came from. I've published four books about Tsoi’s band Kino. My photographs illustrate the text. In 1997, I published a book about Aquarium and Grebenshchikov, the band’s lead singer, found me the publisher. Back then, there weren't any printing presses in Russia which could produce decent reproductions of my photos. The book’s print quality was just awful, I cried when I saw it. In all, I've written six books about rock music and now I'm working on my seventh.

I had a publisher in London for ten years, (Seagull Publishing House Ltd) and last year, I finally opened my own publisher in Russia, Lukomore in St Petersburg. This was despite ferocious resistance from my compatriots. Professional achievements are just not taken into account in Russia, they don't want to accept women as creative personalities or business partners. What's happening today in Russia's foreign policy is no coincidence. It's an expression of an inner chauvinism and national mentality. Now we're preparing to release our first book, a guide to Viktor Tsoi's St Petersburg, Around Piter with Tsoi. We look at interesting vignettes from Viktor's life and the places where he lived, studied and made friends.

Everyone has their own impressions of Tsoi. I never read his biographies if they’re by people who never met him, but I understand there are different views. Some say stardom went to his head but I'd like to reject that straight away. Once a musician breaks out of his cellar and hits the big stage, playing in stadiums, he owes nothing to the people who've been taking the mickey out of him the whole time, telling him he’s a plonker who should stop messing around with the guitar and get a ‘real’ job and saying his first album was better anyway. But he got on well with people who had supported him from the very start when he was a stoker in that cellar. And he had every right to look down on those who had looked down on him or ignore them completely. We weren't friends, we talked because I was a photographer and he was a musician. We both had the same task; to shoot some groovy pics of a cool group, so we gelled. And our photographs look so cosy and friendly because we enjoyed chatting and found each other interesting. Why shouldn't a photographer befriend the object of her pictures? It helps them to open up their personalities.

Do you believe some people are naturally photogenic? Can you take a great picture of any vibrant personality, or do you need to be on the same wavelength spiritually?

I'm sure you have to try to understand someone before you can take a good shot. I have no opinion about being photogenic. Once, one of my teachers told me there's no such thing as bad-looking people, only poor photographers and that’s what I believe. I know from experience even a beautiful Miss Universe can be photographed so that she looks like a frumpy Karen or a cold-hearted witch. Just as with everyone else, you have to connect with rock musicians and find things in common, of course. Here is an example to illustrate; the concert’s been a great success, really stonking and afterwards, the band comes to the dressing room. They raised the roof and they know it. The whole place is buzzing and then I photograph them. I can see all their emotions because I was part of that greatness, I was there. I’m on the same wavelength, the same vibration; they're not pretending to be hot for the camera; they know they rock. So I go into that dressing room and they're all standing there, looking slick. Around them, everyone's offering them drinks. Some groupie girls are trying to get their hands on them. What should I do to catch their attention? That's where my professional tricks come into play. A mini skirt, of course. So they're looking at me with puzzled faces and my camera goes “Click” and the flash doesn't work. Oh dear! And they all laugh; “She forgot to turn on the flash!” And then I press the button and the flash goes off and that's my shot.

Another musician is Billy Novik. He's not quite my style but one day, when he was playing in Piter, I was hanging around with him in the dressing room of another rocker, Makarevich. I hadn't met Billy before but I was taking his portrait. It turned out great, you can see how playful he was, alive with light shining from his eyes and that's really what he's like! And then I saw his poster in town. He was standing in exactly the same pose, with a turned head, but his gaze was completely dead. Of course, the photo had been taken in a studio with an expensive camera, but there was no living spirit. You need some kind of spark so the shot works out, something conveying the emotion to the viewer. I want to give people who weren’t at the concert the same feeling I had when I was photographing it. The same rush. It's like telepathy, only using a medium. That's the meaning of any art.

Are you still in contact with Russian rock musicians these days? Have political events affected these relationships?

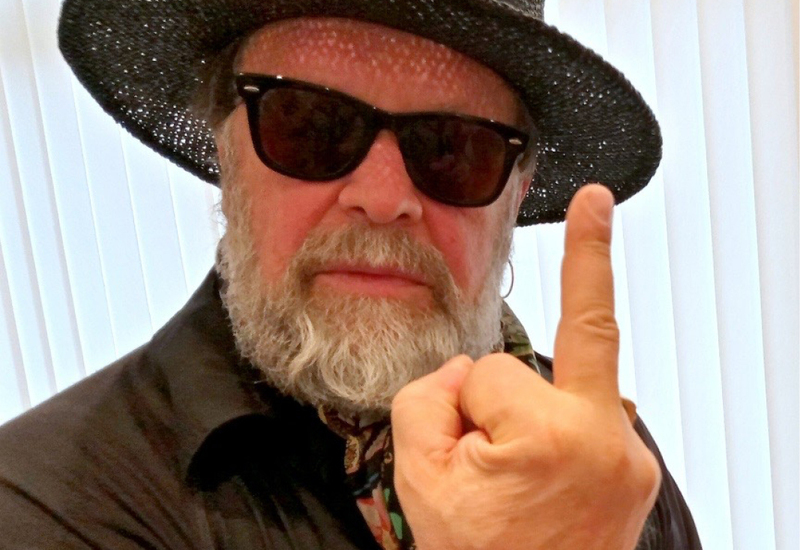

It's easy to keep in touch now with anyone anywhere. I’m still in touch with some of them of course, because we have shared interests. Why not? I've lost touch with some, but the fact I'm in England now doesn't matter at all. Soon, on 30 September, the group Tequilajazzz is coming. Unfortunately, I'm going to Saint Petersburg myself, so I can't be present. Zhenya Fedorov left Russia right after the war started, he went to Estonia at first, but now he's living in Sweden. Grebenshchikov now lives in London. I invited him to come to my meeting but he's on tour. On the 26th he'll be in Montenegro. Still, if he showed up, everyone would gawk at him, of course and no one would look at my slides. But that's just how I started my career nearly 50 years ago, with slideshows and games of Monopoly with Grebenshchikov in my kitchen. Right then and there we had the idea for a rock magazine called Roksi and I was its first editor. I typed the material on my mum's typewriter but then we were raided by the KGB. They confiscated the typewriter, took away the enlarger and all my photo paper…All the same, we had fun. It was interesting. That's the way the spiral turns... Now we're together once more, but in England and I'm showing slides again.

You were the first Russian-speaking photographer accredited to take shots of the Rolling Stones. Did you manage to talk to them? What were your impressions?

Yes, that was the crowning moment of my career! I didn't manage to have a close chat, but I did learn a lot about how things are done in the West. (This happened soon after my move to England). It was 1995 and they were touring for the Voodoo Lounge album. I experienced an enormous culture shock when I saw that stadium, those thousands of people celebrating, the jubilation. Rock and roll wasn't banned, it wasn't underground, it was unchained, without cop harassment. People were rocking and they were all wearing such bright clothes! Then they brought us to one of the dressing rooms where there were 13 photographers. Only two of them were girls, they were mostly men from Brazil and Japan and all of them had fancy cameras. I had two Cannons, one was mine and Seva Novgorodsev, the DJ and radio presenter, had given me the other. At the time, we were making a rock and roll magazine together. One camera had black and white film and the other colour. A girl said to us “Don't worry guys, the Rolling Stones know about you”. It knocked me sideways. After Russia, where I’d always been chased away, arrested and banned, to suddenly get this kind of treatment! The Rolling Stones would pose especially for us because they understood the link between music and photography. Those photos appeared on t-shirts, badges, cigarette lighters, baseball caps, pyjamas, bed linen, books, posters and calendars and all of that brought in a profit. Music is intrinsically immaterial, now you can just download it at the click of a button. You make money by selling merch; physical objects that can't be stolen or faked on the internet. This link between music and photography is absent in Russia, there, they don't let photographers in, they hate them and they ban them. That's why there's no show business there. For that reason, rock music is still underground in Russia even though the underground has now spread to the size of the country. In England, show business is in third place by turnover and share of national income after the arms industry and big pharma, but in Russia, there's no show business at all. They make money from ticket sales and this pays for the venue, security, the cleaner, the lighting and sound engineers. The wider public, the man in the street, have absolutely no idea that Kino still exists, that they've got back together. They know Viktor Tsoi because they've been writing “Tsoi lives” on fences and garage walls for 30 years. In 2021, AST Publishing didn’t release a calendar to mark the 40th anniversary of the founding of Kino. They only got the news in 2023 that “Tsoi lives” and they published this calendar with a print run of only a few thousand copies of calendars for the whole enormous country. But still, people listen to them and love them.

Does that mean Russian rock is more alive than dead?

To me, there's nothing unexpected about what's happening in Russia today. Things had been heading this way for many years. It's just that Russians preferred not to notice: “We're doing fine, we've got supermarkets and cars”. I tried to tell people of my growing sense of dread and that the cops were getting more brutal by the day and they told me that it was my own fault and those were my problems. I see that many musicians have left and now they're playing all over the world. This situation reminds me of what happened at the end of the 1980s when the initial spark of dissatisfaction was at Leningrad Rock Club at 13 Rubenstein Street and then it all flared up and spread all over Russia. I saw what reaction rock concerts produced in small towns like Ryazan or Kaluga, rock music swept through the entire country. And now, 30 years later, It still permeates all of society. You go into a cafe, and the menu is decorated with quotations from Grebenshchikov, or you read one of Ustinova’s popular detective novels, with no relation to music and someone gets into a car and listens to Garik Sukachov, or they do exercise while listening to Shevchuk. Russian rock music, despite its illicit underground nature, is deeply woven into all of modern Russian culture and is an inseparable part of it. Now, these musicians are also going around the world; Spleen, Aquarium, Tequilajazzz and Maxim Ermachkov. It's enough to go to their concerts to understand that Russian rock is alive. Even if rock musicians do not stand directly against the regime their lyrics can still fuel resistance.

Tell us the story of your move to Britain. How did you realise that you could make it here?

I didn't end up in Britain because I had decided I would have more opportunities for creativity here. I came because I realised I couldn't live in Russia anymore. They wouldn't let me work, they messed me around so much that, as a single mother, I had no choice. I had no way of feeding my child. The Soviet system was falling apart. It was the Wild 90s in Russia. The cops were harassing me at the stadiums and taking my merchandise. The musicians had finally burst out of their rock clubs and hit the stadiums but nobody let me follow them there. At last, they were starting to make big money for their concerts, but not me. At the start of the 1990s, a law was issued banning the sale of mass-produced photos, which was just when I was making arrangements with the music stands on the metro. They were buying my 18x24 format pics of Grebenshchikov, Tsoi, Kinchev and Shevchuk. Once they passed that law, everybody refused to take my photos because straight away, they started to fine those stands and close them down. So I just had no other way. Well, I could have gone to the market to sell soap as my neighbour suggested, or worked as a hard currency prostitute. Single mothers in Russia in 1994 just had no other options, except finding a man. But all of these routes just said to me: “Then you’ll have to give up rock music”

I prepared two options; Israel, where my uncle had already invited me, or Australia. There was a programme in that country to settle the interior regions. Workers of any gender and race were needed, with any professional skills, from engineers to cooks. I spent half a year filling in forms and going to the Australian embassy in Moscow. Everything was ready, I only needed the compulsory $10,000 required to tide us over in the first few months after our move. I was waiting for my daughter to finish her final year of college. We planned to sell our room in the communal flat which would just have made $10,000, but while I was waiting, I received an invitation to London from the photographer Yuri Malyshev, who was publishing a magazine here with the artist Vitaly Vinogradov.

I ended up choosing Britain. Incidentally, one of the factors was the weather. I don't like the heat and Israel and Australia are really hot. At first, we moved into a squat for Russian artists on the premises of a former bank in Shoreditch which Vitaly Vinogradov had bought. There was no shower and at night, the artists would gather in the front room to write their immortal masterpieces, drink and listen to loud music and I couldn't get to sleep. The guys advised me to turn myself in and apply for political asylum at the Home Office. They gave me a room at the Ethiopian hostel on Oxford Street, right opposite Selfridges, where I lived for half a year. I remember how I cried at the hostel when they gave me my first set of bed sheets printed with roses. That’s not how they made things in the USSR and I'd never seen anything like it in my life. As I hadn't had time to change any more money in Saint Petersburg, with me I only had £5, a piece of soap and a roll of toilet paper.

Next summer, I managed to bring my daughter here with the help of my acquaintance, an American called Joyce who owned a video company making a film about Chechnya. Joyce wrote an invitation for my daughter and her friend to come here for a Rolling Stones concert; a ‘cultural exchange’. At the British Consulate, nobody saw this as suspicious and they issued the visa in four hours. I remember that when the girls were at the consulate, on the wall there was an example of a completed application form and the photograph was a portrait of John Lennon. When they saw this they realised straight away everything would be fine and that the British Consulate saw a Rolling Stones concert as a completely justifiable reason to travel to the UK. Then they gave my daughter a flat in Lewisham, also as a refugee.

That same Joyce invited me to lunch one day with a friend, a single man who was 38 and had been to Oxford. (Later on, I realised she had planned to hitch us up). We hit it off and started to hang out together. Then he made a move on me, gave me flowers and took me to restaurants. That's how I met my husband.

As a Russian with an alternative, artsy background, how did you get along with a British banker?

I enjoyed his company. He was so well educated; he had studied economics and philosophy at Oxford. We really like to travel, that connected us and we went around all of England and Scotland and went to Wales. (At the time I still hadn't received a passport so I couldn't leave Britain). He was tall, four years younger than me and charming, so why not? He supported all my projects, including the idea of opening a publishing house. Everything would have been fine if it hadn’t been for his way of seeing women as beings subordinate to men. It turns out I can't do what I'm told all the time. I want to do what I want, not what somebody else tells me to, at least, if we're not talking about paid work. Anyway, it didn't work out.

Do you still work as a photographer? If so, do you prefer modern digital kit such as mobile phones and superlight, mirrorless cameras, or traditional analogue mirrors and film?

I haven't got a camera at the moment because I don’t have the money for one. They only started paying me for my photographs two years ago in Russia, including those of Viktor Tsoi. Despite that, my photos of Tsoi turn up all over the Internet and they all steal them, including Russian Channel One. Now I have a lawyer and we've only just won quite a hefty sum from one of the federal Russian channels for six photographs which they used in a documentary. I also recently signed an agreement with Legion-Media, an image bank where the media can now acquire my photographs. Until I started working with them they didn't even have a rock section, but they do now.

And did Serebranikov use your photos in his film Leto (Summer)?

No, but I went to the premier in Moscow. Sony produced that film in cooperation with an outfit called Fashion Agency, which, not long beforehand, had ordered my photographs for t-shirts. They had decided to make t-shirts of Viktor Tsoi in London. Sony saw them and ordered ten for a promotion and as payment, they gave two passes to the premiere at the Gogol Centre. Also, the main character in the film, Natasha Naumenko, has been my close friend for many years and we met each other there. It was fabulous! The film was really great and I loved it.