The Austrian sociologist, Elizabeth Schimpfössl, who is a senior lecturer in Sociology and Politics at Aston University in Birmingham, conducted 80 interviews with Russian oligarchs while researching her book; Rich Russians: From Oligarchs to Bourgeoisie. This came out in October of this year, published by Individuum. Elizabeth has long lived in London. Kommersant UK talked to her about the reasons for her interest in the Russian elite and how she managed to organise such a large-scale research project.

Elizabeth, your book is dedicated to Russian oligarchs, you have studied in Russia, and in the international media, they call you an expert on the Russian mentality. What, most of all, brought on your interest in Russia and the Post-Soviet Space?

I have always been interested in history and languages. I didn’t use to have any particular connection to Russia, but now, of course, I have many friends and acquaintances over there, and Russia has become part of my life. Initially, I wanted to learn Chinese, but then I found out that it’s four times more difficult than Russian. That’s why I chose the history of the Russian state, which was pretty interesting, and then I added sociology. I finished my Master’s in the History of Russia. I wanted to continue my studies and write a dissertation, but I had to live on something, so I found a job at an organisation involved with development aid. It had links to the British Foreign Office. At the same time, I started studying sociology to get some training in the methodology and, in the end, I liked it so much that I decided to get a PhD and write a dissertation about Russian oligarchs. At first, I had a completely different idea; to study miners’ strikes in Russia in 1998; how did it come to be that, in a society blighted by mistrust and burdened with the needs of individual survival, a collective movement of such scale was born? I tried to bring this work to fruition, but nothing came of it so I put it to one side. I began searching for empirical data for the project about rich Russians in 2008. I started my PhD, and then I continued to research the topic as part of my postdoc work from 2015.

How did you end up changing the object of your research from striking miners to Russian oligarchs?

I wanted to conduct large-scale research into the question of how social structures reproduce themselves across generations and why social inequality is so hard to overcome. I was really eager to do some scientific research that was just for my own intellectual pleasure. I wanted to take on a project which was practically useless, good for nothing, as they say. It seemed to me that studying rich Russians fitted this aim perfectly.

Why did you choose rich Russians in particular, rather than those on low incomes or the middle class?

The theme of wealth has never been a fetish for me. Incidentally, I’ve never been able to recognise luxury cars, for instance, I can’t pick out a Maybach, say, amongst other cars. I thought about what social class to choose for a long time. It seemed to me that if I had to research the working class, I would have to spend years going over the complaints and dissatisfactions of the poor, which is in itself rather depressing. The middle class wasn’t suitable either; I would still be sitting there, wondering how to define who actually is middle class in Russia and who is a member of the intelligentsia instead, and so on in that vein. In the end, the only subject that was left was the rich.

Who do you see as the target audience for your book?

Anyone who is interested either in Russia or the stratification of society, as well as the characteristics of an elite existing in conditions of social inequality.

You did 80 (!) interviews with oligarchs for your book. How did you manage to get in contact with them?

Yes, everyone told me that I had no chance of talking to any Russian oligarchs, and I had no special access to them. At first, I turned to employees of the oligarchs who were in close contact with them, but this turned out to be ineffective; they looked at my cheap shoes and decided not to waste their time on me. I didn’t pass their test. I wasn’t considered suitable to be introduced to high-level people, as they judged me by how I was dressed. The most successful interviews happened entirely by chance; for example, an Austrian lawyer helped me get in contact. (Although he didn’t do this at first, he only did it when he saw I’d already had some initial success). The first to agree to an interview was David Yakobashvili. On Facebook, I wrote to Ilya Segalovich (the ex-CEO of Yandex) and he was quite accommodating, although he had the condition that I had to conduct my research principally for the sake of science. Starting from 2015, I began to request interviews from the press services of large organisations and, although many of them refused, I managed to work with some of them.

Did you manage to talk to the wives of oligarchs?

Naively, I thought that it would be easier to convince their wives to give interviews, as they have more time. But this turned out to be wrong. They only put me in touch with their wives if they had achieved something in their own right, such as a successful career or a charity that they had opened themselves. Unconsciously, oligarchs who spoke condescendingly of their wives seemed not to want their spouses to spoil their images as people of high culture, gifted with rare talent, maybe that’s why they didn’t let me speak to them.

What did you pay particular attention to during your research?

My main task was to understand how rich Russians see their place in society. It goes without saying that I asked them how they became so rich and successful. Some of them replied that it was all thanks to the wonderful genes that their parents had bequeathed them. Pride in their exceptional genes was strengthened by the idea that the sophistication and intellectual development they had acquired through their own efforts had helped them to become efficient and disciplined, which had also facilitated their success. I paid special attention to the topics of charity work and philanthropy.

Do Oligarchs’ approaches to charity vary?

A contrast was perceptible between oligarchs of Russian and Jewish backgrounds. Jewish oligarchs always had a plan of action, scheme or strategem, as well as scores for measuring progress and improvement, while the Russian Orthodox philanthropic tradition dictates that donations should be made with no expectation of reward; ‘from the breadth of the soul’, as they say. Philanthropy in the spheres of art and culture helps sponsors to acquire a certain prestige. It’s no coincidence that rich patrons of the arts are widespread around the world. Many of my respondents told me that in the 1990s, they were pleased with their ample fortunes and the unusual freedom it gave them; they felt like children in a toyshop. Over the years, this euphoria died down, and the time came to look for something spiritual, with meaning. Many of them started to leave enterprise and go into full-time patronage. They transferred their businesses to other people, sometimes to their wives. Oligarchs have a tendency to help children, especially talented ones. They see the future of the country in them. When viewed against wider society, this seems more unusual, as, in Russia, even those who can afford to are typically not burning with enthusiasm to give to charity. One billionaire explained to me that this was due to the high level of distrust in Russian society. There is also gender inequality; amongst Russian oligarchs, many more men than women are involved in charity. In the West, the opposite is true.

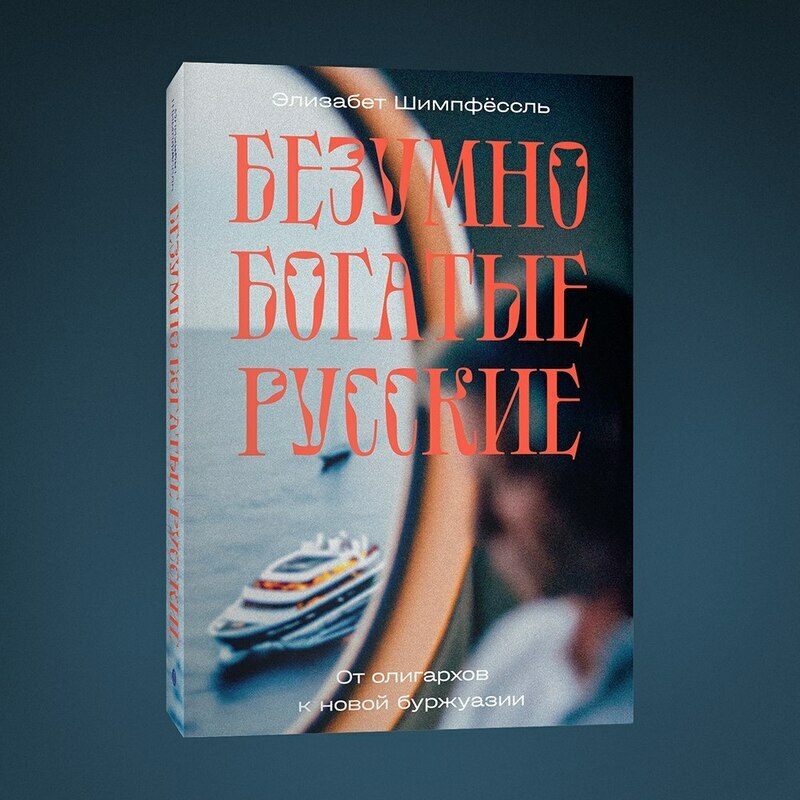

The book about oligarchs came out in English in June 2018, published by Oxford University Press. However, it was only possible to bring it out in Russian this autumn. Was this due to the unwillingness of Russian publishers to accept your work? What caused this delay?

Initially, one publisher (one of the largest Russian publishers of books), took on my work and made two translations, one unsuccessful, and the other successful. And then they disappeared somewhere. For several years, I tried to find out what had happened to my book. For a long time, they were silent, and then, they finally answered that going ahead with it was no longer relevant. Later, I heard rumours that they were frightened of publishing it as books like this can lead to revolutions. In the end, my book came out in Russian at the end of 2022, published by Individuum. They worked very quickly and professionally.

Some of the people in your book appear under their real names, while others are anonymous. How many of the 80 interviewees are given their own names and surnames? I suppose privacy is especially important for oligarchs.

Roughly 20–25% of the interviewees appear under their own names. There are two sides to the coin here; I didn’t want any problems, but, with anonymity, a lot of information can be lost. That’s why I separated the information from anonymous sources from that provided by those who didn’t hide their names. There was one person who displayed clearly chauvinistic views during the interview, comparing himself to Chekov (apparently, the only difference between them was the number of works they had published), I made him anonymous. I did it very carefully. It’s important for the anonymised figure to be similar to the original. For example, when describing him, I chose a similar name, mentioned a similar educational establishment and occupation etc. A lawyer specialising in the area of libel works with the publishing house to check memoirs and biographies for statements that could result in them being sued. This expert is worth his weight in gold; he checked my writing thoroughly and pointed out a series of issues to which I hadn’t paid attention. For instance, when I described anonymous respondents, I tried to present them in an attractive, favourable light. However, he told me that I had to strive for accuracy in my descriptions, even if the results were unfavourable to interviewees. I should accentuate their less pleasant qualities, whether physical traits or features of their personality.

Why so?

As he explained to me, people much more rarely make a fuss in defence of an unpleasant character, even if they suspect that it might actually be them. It might not even occur to some people that the unattractive figure described in the book is in fact their own selves. Overall, there is no guarantee that someone won’t get angry or feel insulted for some completely unforeseen reason.

Did you barrage the oligarchs with inconvenient questions? Which topics were taboo?

Some of my respondents held certain topics to be inconvenient, but these were isolated incidents. All in all, there was a lot of variety and everything depended on the individual. For instance, one respondent didn’t want to discuss the topic of charity; as he put it, it was a very personal question, and apparently, if you start saying that you’re a philanthropist, then what you’re doing can’t be philanthropy. One of the topics that was absolutely taboo that I could name is cosmetic surgery and the use of Botox. Also, from day one, I promised all my interviewees that I wouldn’t ask them about business or politics; after all, I’m a sociologist and not an investigative journalist.

What stereotypes about oligarchs can you confirm, and which can you deny?

There is a stereotype that the moneymen in Russia are oligarchs, whereas, in America, they’re IT geniuses and philanthropists. They say that in the West, the rich are good people, while in Russia they are bad, and structural inequality has nothing to do with this at all. However, the concept of an oligarch has no nationality; they are rich people who use part of their own wealth for future expansion. Wherever there exists an extreme level of social inequality, allowing rapid growth in capital, oligarchs can arise. Writing in his blog this spring, the French economist Thomas Piketty formulated this thought like this: ‘everything is done to distinguish useful and deserving western “entrepreneurs” from harmful and parasitic Russian, Chinese, Indian or African “oligarchs”. But the truth is that they have much in common’. In my view, it’s very difficult to explore the nature of Russian oligarchs when there is an ideology which decrees that they are bad a priori. In essence, this characterisation is borderline racism. Research into non-Western elites is usually only considered meaningful when one group is compared to elites which have emerged in other less-developed countries (for example, when the Russian upper classes are compared to their counterparts in China, India or the Arab states).

Why?

The thing is that study of these elites, who are outside the Western World, may reveal significant traits which are also present among the upper layers of society in the West. The ease with which rich Russians have, historically, expressed their thoughts gives us a unique chance not only to understand them, but also members of the elite around the world. This is very important from a sociological perspective.

What was the reaction of the English-speaking public to the publication of the first edition of your book about the Russian oligarchs?

Some commentators in the States decided, for some reason, that I am on the Kremlin’s payroll. However, most of the rest of my readers understood why I had written this book. I have never said that I support the policies of Russia or the US. I try to maintain my neutrality. Overall, I was pleased when I found out that my book had not just been read by sociologists and experts, but also by people who are not so closely involved in the subject, and that many of these people had read the book from cover to cover. Some of my readers wrote to me that they were horrified; they thought that the characters in my book seemed to be competing with each other to see who was the worst. Many people asked me if I had had problems after the book was published. I have never understood this concern; it’s not that the participants of my research project sent me thankyou letters, but, for the most part, I have the impression that they valued quite highly my scientific efforts, which were based on many years of study of the subject. I also think they appreciated my attempts to explain how they see the world overall.