Viktoria Saltykova, a young entrepreneur from Moscow, went into business during her student days. Today she owns Project Life, one of the most successful commercial genealogical projects in Russia. Her boutique offers the tracing and restoration of full family histories for the last five centuries, providing services for people in different countries. Viktoria tells us that the list of her clients includes famous business people and politicians. In her interview with Kommersant UK, Viktoria told the tale of how, as a young girl, she had the idea of getting into this unusual area of business, explained what makes the product unique, and why, for anyone interested in their roots, the best selling book The History of You is a must-read.

How did the idea of creating a project related to genealogy come to you?

I was born into a classic three-person Russian family (Mum, Dad and me), and I didn’t have much to do with our other relatives. Nevertheless, I always wanted to know more about them, which is why, at the age of 21, I opened a company which helps people to get to know their roots. At first, I was even surprised myself by how it happened because I had never wanted to be an entrepreneur. I had planned on becoming a civil servant, like my mum. But then Dad remembered by chance that my great-grandfather, a Don Cossack, had been a successful entrepreneur in Rostov Region and his dream had been to pass for his family to continue his business. That was when the pieces of the puzzle came together and I understood that I was on the right course.

Tell us about your project. What does it do and who can use your services?

Project Life is a large company which deals with the recovery of family histories and the preservation of family heirlooms. I started to build it up eight years ago, when I was still quite sceptical about the sphere of genealogical services. The trend of studying your genealogy arose in the 1990s, but then the main aim of clients was to confirm their affiliation to famous dynasties; people would pay several million roubles for this service, although results weren’t guaranteed.

I wanted to provide a quality product meeting the very highest standards, but which, at the same time, would be easy to understand and accessible to all. A few years later, I realised that it wouldn’t be possible to create something that was affordable to a wide range of people, because each project required the work of at least eight specialists who spent several months on the family history of each client, and this is an enormous expense. This is why we chose the path of a progressive premium-segment company. The people who come to us understand the value of money, and they are clear about what service they require and how much they are ready to pay for it.

We have a very wide geography, we work in 18 countries, including Russia, former Soviet countries, Germany and Switzerland. Anyone can come to us; sometimes people with Russian roots come to us who are second-generation immigrants and don’t even speak Russian. We really love working with them, although, in Russia, in my view, the process of genealogical research is one of the most difficult in the world, as many archives have just not been preserved, and they still haven’t managed to digitise some of them.

What specialists work with you and why does one project take so much time?

We currently have 80 members of staff at our company, and 35 of them are historians. We’re working on 75 projects simultaneously and we finalise from ten to 20 each month. A standard geological investigation takes six months, while writing up the genealogical research takes from six months to half a year. Then, using the historical facts that we have established, we write a book. Genealogy is a complicated process, sometimes we have to wait three months to receive each piece of information that we have requested. In the first half year, we ask our clients to stock up on patience and trust us. What’s more, we follow the principle that ‘nothing is true but the truth’ and we’re very careful with information. We check every document against a minimum of two or three sources. If we find someone who seems to be connected to the family, we try to check this in various ways because the information in different documents can be conflicting.

What does the process of looking for ancestors look like?

At first, we conduct interviews with all members of the family. This is an important step, and sometimes the most difficult, because the human brain, unlike archived records, has the propensity to forget things, or, conversely, to remember things that actually never happened. For instance, many clients are absolutely sure that their ancestors were aristocrats. We also had a case when a client affirmed that the person who raised them wasn’t their birth father, and he turned out to be right, but his mother, who knew that the client’s biological father really was another person, had excised this fact from her memory. She sincerely believed that the real father of her child was his stepfather. This is a peculiar form of psychological self-defence, of which there are many examples. However, what happens more often is that in the course of the interviews, important details about the family history are revealed. For one project we conducted 18 interviews with the client’s relatives and we established that, amongst other things, her grandfather, with whom she had lost contact, was a veteran of World War Two, as well as a prize-winning teacher who had dedicated his whole life to education. He had ended up vice-minister of education of Buryatia. With the help of the internet and literary sources, we managed to draft a portrait of him in life, drawn from the comments and reminiscences of his colleagues and acquaintances.

The second step is working with home archives. The law specifying the period for which personal data can be retained stipulates that any person can contact the registry office, confirm their relationship to the person they are interested in, and recover documents which have not been passed down (they are kept in the archive for 75 years). On social media, we also contact relatives who may not be in touch with the family but who may have important information. Next, we systematise the information we have gathered. Usually, this is done with the help of special genealogical programmes such as Ancestry or Tree of Life, as well as digitised archives, which are always being updated. Then comes the most fascinating step; working on location, in the places where people’s ancestors lived. We go on expeditions and study various paper-based archives; state and departmental records etc. We go to the local museum and the cultural centre, as well as the cemeteries; visiting them is a must. We also ask the locals questions. On occasion, elderly ladies who live in the neighbourhood know more than the relatives do.

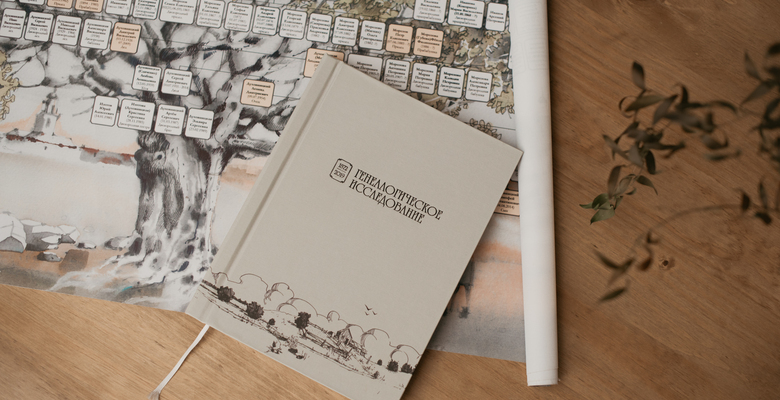

Usually, after the first stage, the client learns the history of 25 relatives; parents, grandparents etc. After six months, this rises to 200 persons, amongst whom there are husbands and wives, cousins etc. In the end, we present the whole family tree in a ceremony. This can be in different formats such as a book, site or film. Recently, we presented a project in Irkutsk for which our clients hired a whole cinema and invited their relatives and friends.

Then, the independent work of our clients begins; many decide to continue the traditions of their ancestors by trying to preserve the most interesting customs, such as special recipes for okroshka (a cold soup) which take three days to prepare, or creating baubles for the Christmas tree decorated with photographs. Some organise a family museum.

What do you think; why are people interested in learning about their family histories?

In the Maslow Pyramid, the need for self-knowledge is valued highly. When people have dealt with all the challenges they face, found their own place in the world, begun to feel secure and started a family, they begin to ask the questions ‘who am I? Where am I going? What values can I pass on to the next generation?’ These are the most important philosophical themes which compel us to study our genealogical history. Beyond that, goals differ. Some people want to clarify their lineage and understand their family from a psychological perspective. Some people don’t feel a strong connection to their relatives, instead wanting to do everything for themselves. For many, researching family histories is becoming a hobby. In the US an article even came out devoted to this topic, and it turned out that, on the list of offline pastimes, genealogy is the second most popular after gardening, and that the amount of time spent on genealogical sites is second only to porn. Sometimes, clients are very interested in their roots, yet, until the last moment, quite doubtful. When we first begin work on a new project, we often hear ‘I have an ordinary family, I have no outstanding relatives, so there probably won’t be anything to talk about’. And when we come to the final presentation, it lasts over two hours. Could we really find so much to say about something that wasn’t interesting?

Do you have any favourite stories?

Yes, some time ago we did a project which is still giving the whole team goosebumps. A world-famous person came to us who wanted to know more about their family. We studied his ancestry back to the 1700s. We found that three of the four branches of his family that we studied were aristocratic, and that is unique in itself. What’s more, several of his relatives from one branch of the family renounced their titles and became ringleaders of the 1917 revolution, whilst his great-grandfather from another branch led a commission which investigated the murder of the Tsar. There were so many intertwined contradictions all in one person.

There was also an amazing project that reunited a family. A lady called Margarita came to us. Her dad, Aleksander Sergeevich, had never seen his father; his parents never formalised their relationship and they parted fairly quickly. From his early years, Margarita’s father was brought up by his stepfather, who gave him his surname and patronymic. In his turn, Margarita’s biological paternal grandfather soon started a new family and had two children. The families lost touch for decades. However, several years ago, Aleksander Sergeevich decided to seek out his father; it was important for him to know if he was alive. All he had to go on were the names of his half-brother and sister. He attempted to get into contact with the family independently, but, unfortunately, this was unsuccessful. When Margarita asked us to conduct genealogical research, the task of finding information about her biological grandfather was one of the priorities. Our historians noticed Alexander Sergeevich’s half-brother and sister on Odnoklassniki (a Russian social media site), and they wrote them a message. However, from their profiles, it wasn’t clear where they lived or how often they logged onto the site. After several unsuccessful attempts to contact his step-sister, we eventually had some success; her husband saw the messages and wrote to Margarita, who showed his message to us. It turned out that Alexander Sergeevich’s father was alive. He was 84 years old and he was living at his daughter’s house in Krasnodar. He had tried to find his son himself, but, since his surname and patronymic had been changed, he hadn’t been able to do so. Soon, the whole family set off for Krasnodar, where the long-awaited meeting finally took place.

You call your method of finding ancestors genealogical archive-detective work. This description brings to mind the characters from an Agatha Christie novel and the cunningly woven tales surrounding their origins. Whose story reminds you most of the plot of a novel?

We had one case where some clients knew that they were probably the descendants of an aristocratic family (unlike so many who only hope for this). They wanted to know about the lives of their ancestors in greater detail. Our historians managed to provide them with facts. At the end of the nineteenth century, the client’s family had been members of an old aristocratic line from Ryazan Governorate. They owned large areas of arable land in the region of modern Sochi. They ran hotels, held posts in the civil service and were very influential in the development of the region. Our customer wanted to know at what time these people had first married outside their social class. It seemed obvious that this had been after the revolution, but in fact, this wasn’t the case. Actually, it happened in 1913, when one of the client’s direct ancestors married a lady who was a burgher from Kharkiv. He was a larger-than-life personality who stood out for his radical left-wing views. This disproves the widespread myth that all aristocrats were conservatives who didn’t want change. He went to a school of agronomy in Switzerland that three of his brothers had also attended. Having returned to Sochi, he took up gardening. He had his own plot of land where he planted apple, plum and pear trees, and a pond where he kept mirror carp. In 1905, an armed uprising broke out in Sochi as part of the first Russian revolution. He took an active part in the protests against the tsarist government, calling on the soldiers to lay down their weapons. Knowing how he reacted to the 1905 revolution, we may suppose that, 12 years later, he greeted the February Revolution enthusiastically. We probably can’t say what he thought of the Bolsheviks. However, we know that he voluntarily donated his plot of land during collectivisation. In the 20s he worked on the state-owned Lenin Farm, (or ‘Sovkhoz’), but in the 1930s, he faced repression; he was arrested and sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment. The fates of other members of his line after the revolution varied. Some were arrested. One found work at a film studio as an animator, while another pursued a military career (incidentally, according to his documents, this individual was of peasant origin and not from an old aristocratic family). In order to find out these and other details from the lives of the client’s ancestors, our historians studied sources such as parish registers, ‘memorial books’ (a kind of regional official reference book in Tsarist times), the collections of the Russian State Historical Archive and also museum records.

Has the international situation which has developed over the last year affected your work or the fate of your clients?

I can say for sure that many of our old clients are now using the documents we found for them in the course of work on their projects to apply for citizenship in other countries. A new trend has appeared. People are coming to us with the aim of emigrating to countries with which they have a family connection (‘repatriation’). I note that in roughly half of our projects, Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian roots are intertwined, and sometimes even Polish and Baltic origins as well. As research has shown, most of all, this intermixing occurred in the nineteenth century, when mass migration began. There are practically no examples of people whose ancestors are all from, say, Ivanovo Region. The world is made in such a way that everything in it is connected. Some people may not like this, but that’s the way it is.

On the site of Project Life, you can choose the service ‘trace wartime path’. What does this involve?

This is also genealogical research, but here the accent is on the fate of relatives who fought in wars. We research their wartime paths; where they were posted, under whose command they served, what awards the regiment received, as well as the individual soldier. We find medals and commemorative awards. We also collect on our site all the available active links to open online archives, free-access sites with official information about people who fought in the war. One of the most important of these resources is the official site of the Immortal Regiment movement, where you can find information about World War Two.

During lockdown, you launched a platform called istoriyatebya.ru (the History of You). Tell us about this project.

The History of You is a free, educational medium which informs about questions of family history and related areas. We talk about what genealogy is, how to begin a search for ancestors and why this is worth doing. Over the last year, the details of the project have changed and separate sections have appeared. For example, on how to look for relatives in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan or Lithuania, and about the specifics of searching for ancestors who were Don Cossacks, Jews or Gypsies. Also, on the site of the project, you can buy our book, The History of You, which we wrote together with Michael Katin-Yartsev, a specialist on the Baltic-German nobility and the first official genealogist in Russia. Over 40 different specialists worked on the book, including genealogical historians, heraldists, archivists, family book compilers and professional lawyers. This allowed us to make the book interdisciplinary, large-scale, and also interactive. In the book, there are many QR codes leading to relevant databases and sites with music or videos related to the topic. In Russia, the book became a best-seller and I hope that in England they will also learn about it.

What do you plan to do next?

Project Life is difficult to scale up, which is why, so far, we are just trying to keep up our pace, doing ten to 20 projects a month and working with schoolchildren and students. Once a week at our office at Kuznetsky Most (a street in central Moscow) we give our master classes on family history. It is surprising, but I have noticed that generation Z (who they also call Homelanders), are much closer to their families than we are. My generation are achievers to a significant degree, more focused on their careers, but modern children feel there is something important about this topic that they identify with. We would love to hold similar events in England as well.