British social housing, or to be more precise, subsidised housing provided by councils is a hot and bitterly-disputed topic. Many people need it, and almost invariably, it’s only possible to help them after a long delay. Demands to increase the volume of social housing built are countered by protests from the residents of areas assigned for its construction (so-called “nimbyism”, from the phrase “not in my backyard”- translator’s note). Projects are also stymied by the quiet sabotage of developers. It would seem that the problem of housing the most vulnerable is a question for the country as a whole, as none of us have a guarantee that we won’t fall through society’s cracks. It follows that, by preserving social institutions, citizens are indirectly looking after themselves. Nevertheless, discussions of social housing are often subject to unspoken censorship. Possibly this occurs because while social housing provides roofs over the heads of the most helpless members of society, it also creates new difficulties. Difficulties which are awkward to talk about because any serious, informed discussion of them raises the issues of ghettoisation, discrimination and intolerance. Kommersant UK journalist Alexey Gusev gets to grips with this complex topic, carefully, but without avoiding difficult areas.

Bonus: expert commentary from the architect Alexander Rakita and the developer German Abel.

A “Dream House”

Let’s say you fit all the criteria and you’d like to apply for council housing in the UK. Whatever region we consider, a rather windy and troublesome road awaits you. The procedure has many stages, through which you’ll have to painstakingly work with no guarantee that you’ll get your hands on the keys to a subsidised home at the end.

Initially, you need to apply to the local council. This application needs to conform to local regulations; each council has its own. Despite the existence of national criteria setting out who is eligible for social housing, local councils can either impose additional restrictions or make exceptions in special cases.

In each council, there is a waiting list or queue of candidates, so it’s useful to find out how long you’ll have to wait, although even this information is hardly likely to end up being accurate. The council decides who should receive housing first using a points-based system. The homeless, people whose health is at risk from their current accommodation and people in especially straightened circumstances have the best chances of being quickly housed. If you don’t fit into any of these categories, people who do will be given a home before you, even if they apply a long time after you.

What happens next resembles a series of challenges you haven’t asked to take part in; depending on the resources owned by or available to the council, and the plan of action they propose, you are thrown into a search for a suitable flat that can last many days. Either you look for offers independently and carefully investigate each to see if it meets the council’s conditions, or you add your own requirements to the standard criteria to exclude options if it is clear beforehand that they are unsuitable for you and send your list of requirements to the council. As soon as options appear that the council may assess to be suitable, you must quickly take a decision. It’s inadvisable to reject an offer, as this won’t help you in the future. Any inconsistency risks the loss of your place in the queue and may even result in your application being rejected.

Research conducted in 2022 using information from the ten councils experiencing the highest demand for social housing has shown:

More than 30,000 people have been on the waiting list for over ten years,

It is normal to wait two years or more,

In Newham, Sheffield and Leeds there have been cases of people waiting over 50 years.

The record waiting time is held by an inhabitant of Sheffield who has been waiting 62 years (!).

It follows that no one knows what kind of housing they’ll receive or what rent they’ll have to pay, or more importantly, whether they’ll be housed at all. Over the course of a long procedure, many for whom social housing is not the only way to find humane living conditions are either sifted out or simply become stuck on the list indefinitely. Many feel frustrated, and the arguments this issue provokes are never-ending. Some manage to go through this procedure quickly and, as a result, receive housing that exceeds their expectations (this does actually happen sometimes). When they recount their experiences, others receive this as testimony of the authorities' unfair social policies.

It would seem to just be a question of building enough housing for everyone in need. Wealthy countries have enough resources to do this. Why not solve this issue once and for all, turn the country into an enormous building site for a couple of years and never have to worry about this question again? Grandiose plans to build social housing are indeed made, but in fact, at the end of the 2010s, when around 100,000 new social housing units were needed each year, fewer than 10,000 were actually built. For comparison, in the 1950s the annual figure exceeded 100,000 new homes. Why is this so? And why will there never be enough social housing? To answer these questions it’s worth taking a look at the concept of social housing itself, to understand its utopianism.

An idea overturned

The provision of mass social housing is a product of the industrial revolution. When peasants from the countryside were drawn into the cities by the opportunity to work in the newly opened mills and factories, urban conditions became cramped. The first social housing was built by the factories themselves. Cheap living places not only solved the labour shortage, but they also made it possible to make savings on wages and have an additional lever to motivate the workforce, as unsatisfactory workers risked losing their homes as well as their jobs.

By the turn of the twentieth century, subsidised housing was concentrated in the hands of factory owners and charities, but soon the state became involved. In contrast to manufacturers, who were acting out of self-interest, and charities which helped those left behind by the side of life’s road, the state was primarily interested in security, seeking to clear slums that were seen as unsanitary hotbeds of social unrest. But World War One led to a reassessment of this policy. It was in response to the war that the concept of Homes for Heroes was born; the state owed soldiers returning from the front flats worthy of their contribution. From that time, in the eyes of the state, the role of social housing has changed somewhat. As well as a way to put roofs over people’s heads, it began to be seen as a tool to facilitate rapid rehabilitation to peacetime life. This potential for social improvement proved so attractive that it was decided to extend the experiment to those who had fallen through the cracks in society.

The idea behind the modern concept of social housing is more than noble; to help the most vulnerable in society withstand temporary difficulties with dignity and stimulate them to find firmer footing as quickly as possible. Ideally, this can be a completely win-win situation as it can save people from ending up on the street while the state will have in its possession a sort of long-term hotel with a series of tenants, allowing help to be provided in the future as well. However, in reality, this idea has little chance of being realised successfully.

In truth, social housing is more of a trap than a helping hand towards sunny uplands. People are weak, so when they receive some form of subsidy, they soon get used to the idea and begin to take it for granted, rather than trying to change their situation to allow another person in greater need to receive it in their stead. As a result, the savings they make on rent and the extra resources (however paltry) made available for the creation of a more secure life act as a sedative rather than serving as a stimulus to help people fight their way out of precariousness. If council tenants are surrounded by peers who are just as much in need as they are, the likelihood of escaping the pit of dependency becomes virtually nil. They observe those around them, join in the general atmosphere of resentment and fatalism, lose faith in themselves, and stop trying.

At the same time, it’s important not to forget how this housing is generally perceived; a place where no one would live if they had money. Council housing puts a stigma on its tenants. In British society, it may be politely not talked about, but at times a look can say more than words. So social housing, created to help people, in fact slowly kills them, gradually dissuading them of their chances of improving their lot and depriving them of the will to change anything.

The fruit of irreconcilable contradiction

The main purpose of social housing is not to deplete the already empty pockets of those in need. At the same time, it should not place too great a burden on the owner who is subsidising rents which are below market rates. This owner is most often either the state, a state-owned company or a special fund. This means that, on the one hand, social housing should be inexpensive to build and reliable, on the other, its upkeep should not give rise to exorbitant costs. Additionally, the homes should be fitted out exclusively using budget materials, both for the interiors and facades.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the ideal solution to this task seemed to be panelled high-rise buildings, or more precisely, whole complexes of them with their own shops, schools, services and leisure areas. Each home housed hundreds of fortunate people at once, each tenant paying only a small contribution towards the costs of the land and provision of water and electricity which were shared by all. A seeming idyll.

Following these principles, in 1954 St. Louis, in the American state of Missouri, the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing project was built, which became a symbol of the failure of the idea of social housing in the format of highrise estates. Consisting of 33 11-story buildings, the estate was the first major project of the architect Minoru Yamasaki, who later gained fame for the World Trade Center in New York. Low-income families resettled from slums received modern flats equipped with what were modern conveniences for the time. The project appeared progressive, although the large concentration of low-income families led to the area transforming quite swiftly into a ghetto. By the mid-60s those who could move out of the estate already had, and the area acquired an unfortunate reputation as a place where vandalism, theft and violence were commonplace. Many residents became involved in robberies, prostitution and drug dealing. The housing blocks, which were 91% occupied in 1957, by 1971 had an occupancy rate of 35%. Police patrols answering callouts frequently came under attack. Eventually, the decision was taken to vacate the entire complex and pull it down. The first tower block was blown up in 1972, and its destruction was shown on TV. Later, Yamasaki admitted that he regretted having built the estate.

There are similar stories from many countries. In the United Kingdom, there are also a fair number of examples of architectural projects for public housing which were announced with fanfare and later became ghettos. It is sufficient to cite the Pepys Estate, built in 1960 as a symbol of the social policies of the Greater London Council, which has, two decades later, become a hotbed of crime and antisocial behaviour. Many remember the demolition of the Red Road Flats in Glasgow in 2015. Erected at the end of the 60s, the development was at first seen as a paragon of modern architecture, but later as the epitome of poverty and social problems. However, the concentration of subsidised flats was not the sole cause of this.

A time bomb

The unpleasant truth lies in the fact that when all’s said and done, no one really needs public housing apart from those who really have nowhere else to go. Developers and building contractors don’t need it, since the construction of housing for the middle classes brings significantly greater profits. The municipality doesn't need it, as finding space for it is onerous when there isn’t enough for more interesting projects. The authorities don’t need it as its construction requires supervision, its long-term upkeep is a drain on the budget and it is also a potential source of social unrest. Local residents don’t want social housing built next door, as it does not improve the image of the neighbourhood, either literally or metaphorically.

Social housing is a rather risky investment in the area where it is built. Even if it’s a lowrise construction that fits unobtrusively into the street’s architecture, the locals will immediately take note of this kind of housing. It's not only a question of the prejudiced expectation (which, unfortunately, is sometimes justified), that, sooner or later, any social housing will become a hotbed of crime. The issues social housing raises for the life of the area are quite numerous; the potential fall in neighbouring house prices, the question of which nurseries and schools the children of low-income families will go to, and even the growth in competition for reduced, past-their-sell-by-date groceries in local convenience stores. It may be called snobbism and arrogance but this will not cause people’s behaviour to change.

If the idea is to build a series of council houses or an entire housing estate, then the problems will affect the entire neighbourhood. A change to the demographic composition of the inhabitants will automatically lead to changes to the whole atmosphere, causing a migration of those most sensitive to this shift. There are many examples of how the transformation of individual blocks into ghettos has led to the ghettoisation of an entire neighbourhood. And even obvious gentrification measures require colossal long-term expense whilst not always being able to guarantee the desired result. It transpires that moving needy people into prosperous neighbourhoods does not stimulate them to improve their social position. Instead, it has the opposite effect pushing them deeper into need and embittering them further.

Is there no future?

In my view, the recipe for successful social housing which would benefit all has not yet been thought of. Every social housing block has its own lifestyle, at the end of which it becomes a “rookery” (a reference to an infamous communal flat with quarrelling residents in the Little Golden Calf, a 1931 satirical novel by the Russian authors Ilf and Petrov - translator’s note). After this point, it is either pulled down or rebuilt, but the result is the same; either the building physically ceases to exist, or it is no longer social housing. If an ordinary building has a chance of standing for several centuries, a building conceived as social housing can serve as such for a maximum of 30-40 years, although free-standing buildings and terraces have a much greater chance of a long lifespan than tower blocks.

In this way, however much social housing appears on the market, there will never be enough of it. Even if you need a roof over your head and your case is given priority, the local council may simply not be able to help you, at best offering you a place on a waiting list. In other words, until the construction of social housing automatically entails an obligation to solve the problems it causes, social housing for the most vulnerable sections of society is unlikely to appear in sufficient quantities. For each individual city dweller, this means that it is necessary to support the construction of social housing, but it is better not to rely on it in any circumstances. The good news, which at the same time is very sad, is that in situations where people have no one to rely on but themselves, they find they have strengths and possibilities that were previously unknown to them. However cynical it may seem, the lack of hope may help reduce the numbers of those who require social housing, which is far from being the worst solution.

Bonus: expert commentary

Alexander Rakita, architect and founder of the London architectural practice AR Architecture

Does the idea of social housing work or not? Would it be better to just give people the money to rent accommodation in any area of the city?

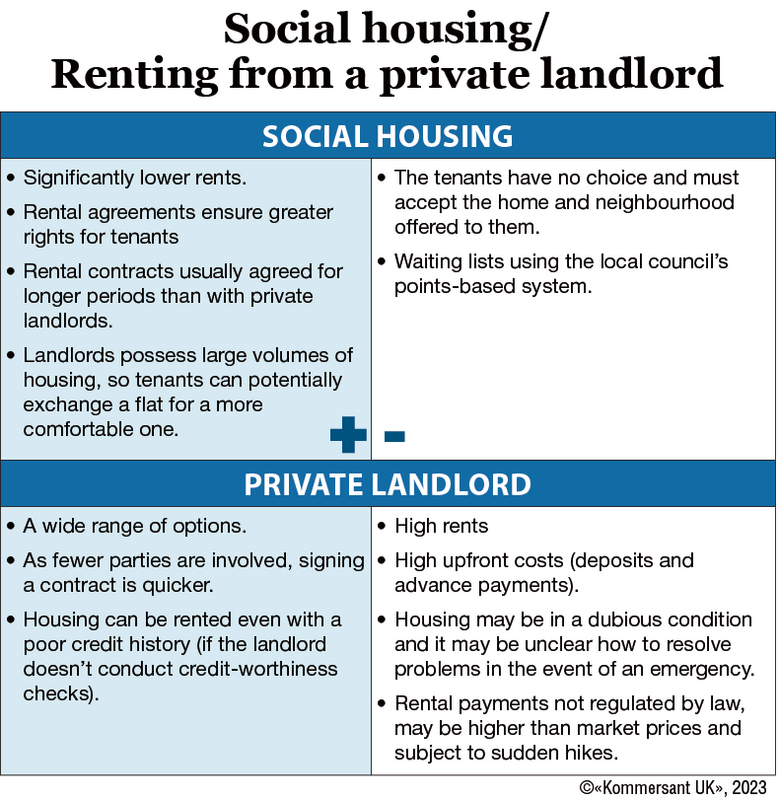

The idea doesn’t work very effectively, but for many social categories there is simply no other alternative; for example, for refugees, unemployed people on benefits or those who have recently arrived in Britain. The thing is that on the private market, landlords choose tenants. They appraise all the potential risks connected to the new tenant, by looking at what recommendations they have received from previous landlords, whether they have regular employment and whether they can pay a year’s rent in advance. Many refugees have none of these things, so they can’t rent, even with the money they are now allocated as housing benefits.

Why is there never enough social housing?

There isn’t enough of it because it’s more profitable for developers to build commercial projects, which is true despite there being less demand for them than for council homes or affordable housing in the current economic conditions. (“Affordable” housing is partially subsidised by the state and is sold at a significant discount). This is while 25% of the floor space of any project must consist of either social or affordable housing. Developers can get around this rule by paying compensation or putting up a building for these purposes separately from the main project. Additionally, a significant proportion of social housing built in the 50s and 60s was privatised by Margaret Thatcher (in the Right to Buy scheme - translator’s note); at that time the conservative government decided that every Englishperson’s dream of having their own house should be realised, so they allowed council flats from the housing fund to be sold (at a knockdown price), and they became private property.

Does the social makeup of the tenets affect how a building is perceived?

Of course, it has an effect; no one wants to live in the same building as welfare tenants. Although modern council housing looks more presentable these days than what they used to build in the 50s and 60s. Some buildings are actually more architecturally interesting than commercial projects.

German Abel, founder and co-owner of the InDome Сapital development company

Does the idea of social housing work or not?

It works well, only there is a housing shortage as demand exceeds supply. Several factors are affecting demand at the same time: a structural deficit of new housing (there is a shortage of over a million housing units), demographic growth and a large influx of immigrants. For instance, in 2022, over 350,000 people moved to Britain, mostly lacking qualifications and on low incomes. They require benefits as well as social housing. This gives rise to heightened demands for subsidised or free housing. But even in these conditions, people usually become homeless out of choice and not because of the housing shortage.

Are there any new social housing projects being constructed?

Yes, because when any housing is built, the developers must either ensure that 30-40% of the units are council houses or pay the local council compensation equal to its worth (based on the cost of the project and the square footage of the housing built).