In the third article in our series, we continue our introduction to British traditions, practices and regulations relating to pregnancy, childbirth and care for newborns. In the previous articles, we discussed pregnancy and antenatal care, as well as labour. Today, we'll look at what happens to mums and babies in the first days and weeks after birth.

Welcome to a new world!

So the magic moment has come; a new person has come into the wide world, made their first entrance and cried, and Mum, frazzled and exhausted, is congratulated by the midwives, becomes captivated by the baby and feels a wave of happiness. Her great mission is done, but the work of the midwives continues.

If the birth has come to a natural conclusion, then, first, the umbilical cord is cut (this honour is usually accorded to the father), after which, the midwives examine the newborn to assess the baby’s overall state. From one to five minutes after coming into this world, an appraisal is made of the baby’s reactions using the Apgar score, to determine if urgent medical care is needed. A bracelet with the mother’s name is immediately put on the baby’s arm and they are weighed (usually their height is not measured). Next, if the mother has requested it in her birth plan, the baby may be rubbed down, dressed and laid on the mother’s stomach; skin-to-skin contact in the first minutes after birth is considered very important for the development of attachment between the child and the parent. For this reason, the newborn is given to the brand-new father to hold, if he is present. At the mother’s request, the baby may lie on her chest for an hour. During this time, the midwives manage the delivery of the placenta. If there has been any tearing or an episiotomy, they put in stitches. After this, the woman and her newborn are taken to the antenatal ward and allowed to relax.

What is different here?

In Britain, newborns are not taken away from their mothers to a separate room. Instead, they are together the whole time and all the checks and examinations of the newborn take place in the ward. At the mother’s request, they can demonstrate how to change a nappy or bring a bath and explain how to bathe the child.

The child’s Apgar score is added to the mother’s health notes. Unless they specifically ask for it, mothers may not find out this figure. It’s not included in the baby’s health record (the “red book”, which is a kind of medical card).

The baby’s tummy button is not burned with brilliant green disinfectant as was still done in former Soviet countries until quite recently. Instead, it is clamped with a special clip and no disinfectant is applied. After roughly a week, the remainder of the umbilical cord falls off on its own.

Immediately after childbirth, the mother is offered a jam sandwich and a cup of milky tea.

Visitors may come to the antenatal ward in any number and at virtually any time of day and stay there for extended periods.

Most mothers and babies are sent home during the first 24 hours after birth if there have been no complications. Here, they don’t organise ceremonial gatherings with all the mother’s relatives to mark the discharge, and everything is quite mundane. Also, giving midwives thank-you presents, much less money, is simply not done here. It’s acceptable to bring something nice to eat for the whole team or to write a thank you letter to the manager of a specific midwife to express gratitude for their work.

At birth, children are issued with “red books”, a kind of medical card, which must be taken to appointments with doctors and nurses for at least the first year of their lives. Records of all vaccinations, increases in weight and other details are all made in this document.

Breastfeeding mothers are not put on strict diets. Instead, they are advised to maintain their usual habits, (except that they must not smoke or drink alcohol, of course).

If no significant problems occurred during the birth, the woman is not examined by a gynaecologist or a midwife. If there was some tearing, a midwife will check how the stitches are healing.

If there are no medical complications, doctors, whether paediatricians or therapists, examine the baby only three to four times before their first birthday, the remaining examinations are conducted either by nurses or health visitors.

For children up to the age of 16 in England and Wales, medicine and dental care is free, courtesy of the NHS (for full-time students, this is extended until the age of 17). In Scotland, all medical prescriptions are always free.

Examinations, Tests and Discharge

During the first 24 hours after the birth (in practice, within three to eight hours), the newborn is examined by a paediatrician, medical staff check the heartbeat, eyesight, hearing and hip joints. They also give the baby a vitamin K injection, as a deficiency of this vitamin can lead to severe bleeding.

If the mother is planning to breastfeed, midwives advise her on how to hold the baby to the nipple. They won’t let the woman go home until they’re sure she’s doing it right. Another important indicator is a full nappy; a normal baby should wee at least once during the 24 hours after birth. The final stage is to ask the parents to place the baby in a car seat and strap them in.

If all the boxes in the regulations have been ticked and the mother feels relaxed and confident during breastfeeding and changing nappies, she and her child are allowed to go home. If the mother or baby is prescribed any medication, this is dispensed directly at the maternity ward.

‘And from this point on, you have to be ready to accept that British medicine has ceased to be interested in you’ Anastasia Santalova tells us, going on her experience of giving birth to two children. ‘While you’re pregnant or in labour, everyone has time for you, but afterwards, you have to wait like everyone else. Although babies are examined according to the regulations, the general system of diagnosis and preventative measures is quite different from what people are used to in Post Soviet countries’.

Neonatal statistics

74% of women who give birth in Britain are in postnatal departments for no more than two days and 22% head home after less than 24 hours. After a caesarean section, women are usually discharged on the third or fourth day.

More than 80% of women who have given birth to premature babies have skin-to-skin contact with the newborn during the first hour after birth.

Studies of newborns show that one or two babies out of every thousand have congenital dislocated femurs. A similar amount has impaired hearing, and eight out of every thousand have a heart defect. These are immediately put on observation and treated.

Around 14% of newborns are transferred to neonatal departments immediately after birth. Approximately 60% of these are full-term babies, born after a pregnancy of 37 weeks or longer. There are five main reasons why newborns are hospitalised; respiratory ailments (25%), various infections (18%), hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar (12%), newborn jaundice (6%) and perinatal asphyxia (2%). The average period spent in hospital is one week, although extremely premature babies can spend several months there.

It has been found that 50 to 80% of women who have given birth experience so-called ‘baby blues’ or postnatal melancholy. Signs of this include sadness, heartache and a tendency to cry. This feeling is not considered an ailment. However, roughly one out of every seven to ten young mothers encounters a more serious problem; postnatal depression or anxiety, which requires medical intervention.

81% of mothers in the UK initiate breastfeeding, compared to 63% in France, 74% in the USA and 98% in Sweden. However, this relatively high figure includes those who attempted breastfeeding for only one day or used expressed milk. After half a year, only a third of mothers in Britain continue to breastfeed and after a year, only 1%. It is believed that only 2% of women are unable to produce breast milk due to health reasons. According to NHS statistics, mothers who are older, more educated, have had more successful careers or are from ethnic minorities with strong traditions often breastfeed for longer. The clients of doulas also tend to breastfeed more. According to the British doula association, six weeks after birth, 60% of women who have used their services breastfed, compared to 24% for the country as a whole.

The NHS has got you covered

Once she gets back home from hospital, the woman and all the members of her household start to get used to the new addition to the family. During these first few days, the NHS comes to see the mother and child.

One or two days after discharge, a midwife and health visitor come to visit the newborn. They weigh and examine the child and answer questions about care, feeding and other aspects of life with a baby. During one of the visits, usually on the fifth day, they do a heel prick test of the baby, in which they take several drops of blood from the heel to test for nine rare but serious diseases such as cystic fibrosis and hypothyroidism.

Depending on the procedures in the specific NHS trust and the mother's requirements, there may be from one to three home visits. The community midwife service observes newborns for ten days and until the 28th day after birth, the mother can go to them for a consultation. At the end of this period, the duty of care passes to health visitors who are found in each district and conduct visits according to a set timetable. During these, the baby can be weighed and the health visitor can answer practical questions of a non-medical character.

Many Russian-speaking mothers do not fully understand the role of health visitors, as they are not medics and can not give medical advice, although they know the standard timeline of child development milestones and the assessment procedures. They often head the mother and baby playgroups which are organised by local councils. In fact, some health visitors can also help to get referrals to a specialist if a mother encounters long waiting times. One of our respondents, the mother of a large family, told us that her health visitor even offered to organise help with the housework after a difficult birth, but, obviously, not all councils in the country have the resources to do this.

Doctors and shots

Unlike in Post Soviet countries, in Britain, there aren’t a great many paediatricians. Both children and adults are served by doctors called General Practitioners (GPs). In emergencies, people are supposed to call 999 for an ambulance. Generally, babies are given priority over other patients in GPs’ waiting rooms.

For the baby, the first scheduled visit to the GP is at six weeks; the doctor examines the child, assesses their development, talks to the mother to assess her mental health and gives her some advice on contraception. From six to eight weeks, the baby has their first injections against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, polio and haemophilia, as well as rotavirus, pneumonia and meningitis. The next rounds of injections are at 12 and 16 weeks, and then after the baby’s first birthday.

Ildar Abdullin, who worked for several years in England as a paediatrician before becoming a GP, has noticed that parents from Eastern European countries are more likely to refuse injections for their children than the general population here. The doctor advises parents not to forgo injections the effectiveness of which has been proved by years of use. In Russia, several regions have seen flare-ups of measles, a very dangerous infectious disease. The reason is reduced vaccination rates in recent years. Measles is extremely dangerous for unvaccinated children below the age of five. ‘I would also strongly recommend parents to consider giving their children the tuberculosis vaccine, which they call BCG or TB here’, says Ildar. ‘In Britain, this vaccine is not compulsory, but the NHS recommends it to children whose parents come from countries with high rates of tuberculosis, which includes most countries of the former USSR (except Belarus, Armenia and the Baltic States). Currently, in several large British cities, the number of cases of TB is rising, so it’s better to be protected’. Also, the doctor is unconcerned that in Britain, it’s not customary to massage infants at three months, as is done in Russia: ‘Massage is always a good thing, but there are no empirical grounds to say that it is necessary if the child has no developmental problems’.

Mental health

The difficulties that may arise on a young mother’s path go beyond physical recovery after childbirth, beginning to breastfeed and sleep deprivation. Women may have problems with their mental health as well. From 50 to 80% of women experience the “baby blues”, the cause of which are thought to be hormonal imbalance, emotional overload and substantial lifestyle changes. Usually, this condition lasts no longer than two weeks and does not require treatment. Postnatal depression and anxiety, which is encountered more rarely but is a more serious problem, can last for years. Far from all women go to a doctor for help, as they may feel ashamed of their anxieties, believing that young mothers should only experience positive emotions. British medicine considers postnatal depression to be a disease requiring special attention and there are procedures for the support and treatment of patients with this diagnosis (incidentally, fathers can also suffer from it).

Anastasia Santalova shares a life hack with us: ‘If you go to your GP with symptoms of a depression which is not postnatal, you are guaranteed a long series of waits for appointments with psychiatrists. But after childbirth, these are arranged very quickly. It is even more effective if, during pregnancy, you complain that you are somehow sad or worried. There are midwives here who specialise in mental health, they can even prescribe antidepressants and refer you for therapy, or group sessions. These are quite useful; they teach you how to deal with this adversity. And you will be guaranteed more attention if you have been flagged in the system as suffering from anxiety or depression’. Other women also advised not to be afraid of appearing to be weak or a bad mother when dealing with the NHS. There is no need to be modest here. At times, it’s even worth exaggerating symptoms to save both your own time and that of the healthcare system.

Getting Documents for the Newborn

From private healthcare, let’s return to issues that all parents have to deal with. At this point, parents must choose a name for the child and apply for their first documents.

Here we must make a digression about nationality, as the child’s citizenship will depend on that of the parents, and this determines the next steps. If the child has the right to the citizenship of more than one country, it’s worth the parents’ while to research the quirks in the respective legislations, as states’ attitudes to dual citizenship differ. For example, Britain, Russia, Armenia and Moldova recognise dual citizenship, while Lithuania, Estonia and Kazakhstan do not. Countries such as Ukraine, Georgia and Latvia only allow dual citizenship if a range of conditions are met. What’s more, the apostille procedure should not be forgotten. An apostille is a special stamp applied to confirm the legality and genuineness of non-commercial official documents issued by one state for use in another. In Britain, applications to apostille documents are handled via the GOV.UK website.

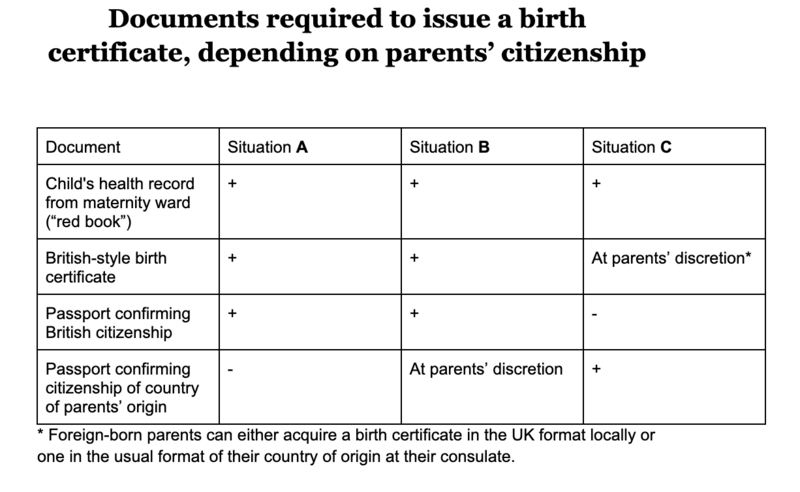

In this article, we’ll look at three situations in which a newborn has the right to UK citizenship:

А: both parents are citizens of the United Kingdom or have indefinite leave to remain in Britain (permanent residence permits);

B: One parent is not a citizen of the United Kingdom and does not have indefinite leave to remain in Britain;

C: Neither parent is a citizen of the United Kingdom and they do not have indefinite leave to remain in Britain.

In situations B and C, we will consider the case of citizens of Russia.

The Red Book

The child receives their first document whilst still in the maternity home: on leaving, all newborns receive a discharge summary with a record of the time and place they came into the world, which is included in their “red book”. This shows the child’s sex and the mother’s surname but does not include the child’s name.

As soon as the parents have chosen a name for the baby, they can apply for a birth certificate.

British birth certificates (in situations A, B and C)

This document is issued irrespective of the parents’ citizenship. It officially confirms the child’s name, surname and other personal details.

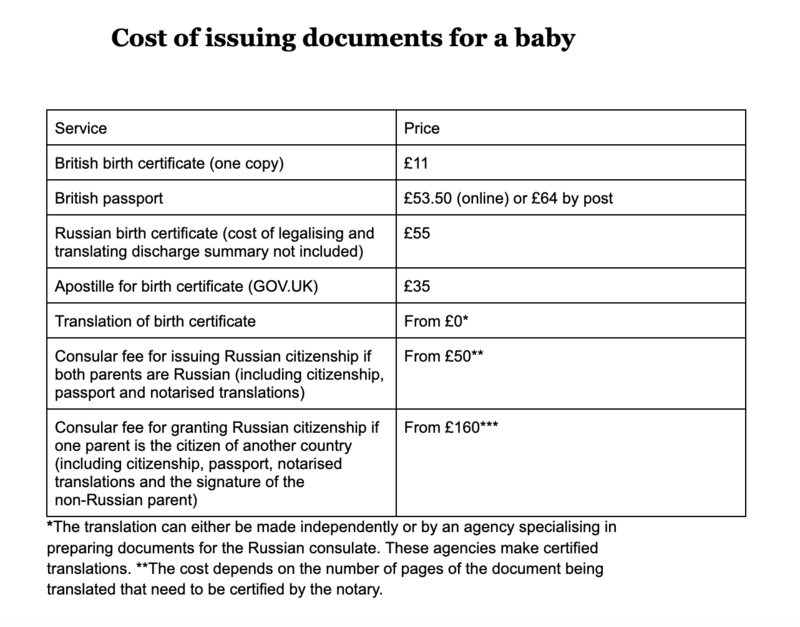

In most cases, the bureaucratic procedure is as follows; in England and Wales, parents have 42 days to go to the register office (the local equivalent of the Russian ZAGS) and register the birth. In Scotland, they must do this within 21 days. They must take with them the child’s health record (part of the “red book”), some personal ID (either the parent’s passport, driving licence or birth certificate) and proof of address (such as a council tax bill). If the parents are married or in a civil partnership, everything can be done by one parent, otherwise, either both parents must come, or a signed statement of parenthood must be provided for the absent one.

There are two types of birth certificates; short form (entitled “certificate of birth”), which only contains information about the child (their name or names, surname sex place and date of birth) and full form (bearing the heading “certified copy of an entry”). These also include information about the parents (their names, surnames, place of birth and profession, as well as the mother’s maiden name). This second type is used more often and is needed, for instance, to apply for a passport. Each certificate costs £11 to issue, extra copies can be acquired at any time.

If you’re planning to travel, bear in mind that in some register offices, you’ll have to wait for an appointment to submit your documents (at times, for as long as two to three weeks) and it’s impossible to make an appointment before the baby’s birth.

Foreign birth certificates (Situation B)

It’s important to appreciate that a child’s birth certificate can only be issued once since this document officially confirms the fact of the child’s birth (do not confuse this with copies of the document). Having received a birth certificate in Britain, it’s impossible to go to another country such as Russia and receive another there.

If both of the child’s parents are citizens of Russia, they can apply for a Russian birth certificate for the child. This makes sense for families who plan to return to their home countries, as in this case, a foreign birth certificate may cause inconvenience.

Russian birth certificates are issued at the consulate of the Russian Federation in Britain. To submit documents, a notarised translation of the discharge summary from the hospital must be made and apostilled, or legalised. The requirement to use the services of a local lawyer or notary may lead to this process becoming protracted. Timing is crucial when doing this; the apostille must be made, an appointment at the consulate secured and the documents submitted all within 30 days of the baby’s birth.

Only one birth certificate can be issued; after receiving a document from one country, it’s impossible to go to another and make one there. This is why, most often, a British certificate is used when applying for citizenship. This must be apostilled and translated into the language of the country in question.

British citizenship (situations A and B)

If the child has the right to British citizenship (which is the case if one or both parents are either UK citizens or have indefinite leave to remain), then on receiving a birth certificate, the parents can apply for a British passport. This can be done later when the need arises; the child has British citizenship automatically from birth.

All the procedures are fairly simple and described in detail on the GOV.UK site. The parents can photograph the baby themselves. An important requirement is to find someone to ‘countersign’ the photo. The eligibility criteria are quite strict; the person must be an adult UK citizen with a valid passport who works in or is retired from one of the approved professions included on a list (for example, an accountant, dentist, social worker, teacher or company head). Also, they must have known the parents either as friends or neighbours for not less than two years. The countersignatory’s signature is to confirm the parents’ identities and that the photo is a true likeness of the baby. The process may become delayed as countersignatories have to disclose their personal information, which not everyone is prepared to do, so it’s better to start looking for somebody suitable in advance and to explain the requirements straight away.

Russian citizenship (situations B and C)

Situation B. If one of the child’s parents is a Russian citizen, the child has the right to acquire Russian citizenship (if both parents desire this). If the child has a UK birth certificate, then, on applying for Russian nationality, the certificate needs to be apostilled, after which a notarised translation of the document into Russian needs to be made. Only then can the application for citizenship be submitted. On doing this, the non-Russian parent must be present to make a statement consenting to their child’s acquisition of Russian citizenship. Applications for both citizenship and a passport can be made during the same visit to the consulate. The presence of the baby is also required.

If the child has the right to more than one citizenship, the Russian consulate requests that the application is made after the child has already received the passport of the other country. For example, the child’s mother may be Russian and the father may have British and Lithuanian citizenship. In this case, on submitting the documents, it is required to present the mother's passport and either of the father's passports, as well as one passport in the child’s name, either Lithuanian or British.

Situation В. If both parents are citizens of Russia, the child automatically receives this nationality, irrespective of whether or not an application is made. ‘It may affect a family’s holiday plans if, for instance, one of the parents has British as well as Russia citizenship, on the basis of which the child has received a British passport’, warns Igor Karzov, an expert on citizenship matters at the IBS VP consultancy. ‘Since it takes time to receive a Russian passport and there are queues to submit the documents, sometimes parents think that it might be quicker to apply for a visa for the child when making a trip to Russia to see the grandparents. But if they do this, the child won’t be issued with a visa. The trip will have to be put off until the child has a Russian passport’.

Acquiring Russian citizenship and a passport for the child takes not less than a month after managing to get a slot for an appointment, which may take one or two months in itself. However, on going to an appointment there is no guarantee that the documents will be accepted. They will be rejected if inconsistencies are found in the information in the parents’ Russian and British passports. In Igor Karzov’s experience this happens most often when the mother has her maiden name in her Russian passport and her husband’s surname in the British one, or when the documents contain different transliterations of “ш”, “ч” and “щ”*, as, previously, French conventions were used. If just one letter is different, the documents will need to be changed and that can take up to half a year. For this reason, the expert advises parents to check their documents carefully in advance, before the birth, to ensure that they conform with the current rules.

*Now transliterated as “sh”, “ch” and “shch”

* * *

They say that, whether a pregnancy is carefully prepared for or unexpected, after those nine months, the woman’s life will never be the same again. We hope our series of articles will give women the information they need to help them make this journey with confidence. Although truth be told, the stages of pregnancy and birth are calm compared to what happens next. So fasten your seatbelts, the real journey is only just beginning.