Is the capital different from the rest of England? Darya Protopopova, a writer with an Oxford degree, has dedicated her latest compilation of Russian language short stories to all Londoners, locals and newcomers. It’s entitled ‘London, Mother***!’. On the back cover, we are told that these brave folk battle with the metropolis every day. In her interview with Kommersant UK, she told us what challenges freshly arrived immigrants must be prepared to face when starting life anew in another country, and she shared her own recipe for success.

What year did you move to the UK and what difficulties did you face?

I moved here in two stages. It all started back in 2003 when I came for an internship at Oxford University after my fourth year at the Faculty of History and Philology at the Russian State University for the Humanities (RSUH). Then I went back to Moscow to finish my degree. After I’d graduated, I returned to Oxford for a master's degree, which sort of flowed into a PhD (my subject was the influence of Russian literature on English modernism). The next stage of my life in England began in 2008 when I met my future husband while I was finishing my dissertation and I decided to pursue a career in England.

In 2008, I had three options; either to return to Russia to teach English literature at university, to stay in England and work at a corporation like Shell, which values Oxford degrees in any field, or to build a scientific career. I chose the latter. All through 2010, I was busy preparing papers for research fellowships and also trying to get my dissertation published as a book. The Oxford professor Hermione Lee, who is a leading Virginia Woolf specialist, carefully edited it, but even so, the university publishers still demanded some additions. Soon, I found I had to put all this to one side, as in January 2011 I had twins. I only managed to publish my monograph, Virginia Woolf’s Portraits of Russian Writers: Creating the Literary Other, in 2019.

In the UK, an immigrant woman, even if she is a linguist, faces two problems: the excessive number of humanities graduates on the jobs market, and the impossibility of combining motherhood harmoniously with a fully-fledged career. I say ‘harmoniously’ because it can be done inharmoniously. You can do it by handing out the best part of your salary to babysitters and nursery schools, and by only seeing your children for the odd hour or two at the weekends. If you do that, these two halves of your life can be combined. Another problem for all immigrants is the recognition of foreign qualifications. For example, after Oxford, I decided to enrol on a teacher training course to get a PGCE and teach at a state school, and I was asked to get my high school diploma recognised. This was an absurd situation because I already had a PhD from Oxford University, but in England, these are the rules. So they evaluated my Russian school grades in maths and science (after Brexit, NARIC, the body that does this, became UK ENIC and the way it was done changed). Then they made me do an English exam. But now I have the official status of a qualified school teacher, which I received after working for two years in a school on the outskirts of London. Unfortunately, immigrants have to either put up with humiliating nitpicking about their qualifications or start the long, onerous process of retraining (my friend, a lawyer from St. Petersburg, has become a baker in London), but if you accept this as an inevitable part of moving to a new country, it becomes easier.

Do you like London? Ideally, which area of the city would you live in?

I like London. It’s not as smoggy as Moscow. This is because of the congestion charges, which mean there aren’t so many cars in the centre. Also, the locals feel no stigma about taking the tube to their offices in the City, which also helps to keep the traffic down. I live in Ealing and this is my ideal area. There is a lot of greenery here, it’s a stone’s throw to the Thames at Hammersmith, and my favourite places are nearby; Notting Hill and Chiswick. For me, the gardens of Chiswick House are the quintessence of an English landscape garden.

Is the capital different from the rest of England?

Yes, London is more cosmopolitan than other British cities. There are a lot of foreigners, so I feel like a citizen of the world when I’m here, rather than a visitor. There are various Russian-speaking communities in the capital; for me this is a nice plus.

What do you dislike about the UK?

For me, the exit of the country from the European Union was a tragedy. As I see it, the idea of a united Europe is one of the positive developments of 20th-century history. It was conceived in the aftermath of World War II in order to prevent international conflict. Now, in the 21st century, I believe humanity needs to unite to save the planet, yet we continue to be divided along national and racial lines. There is a degree of cultural tolerance in the UK; for example, emigrants from Pakistan, India, China and Africa find it easier to integrate here than in Italy. But this tolerance is superficial; racism is present in the UK, as elsewhere. Previously, the country's membership of the European Union reconciled me with the English dislike of foreigners, but now this compensation has gone.

Some may object that by leaving the European Union, the British are trying to prevent a migration crisis such as many European states are now facing and that their cultural identity is under threat from the large numbers of refugees from Africa and the Middle East. You can read about this fear in the books of the Russian Foreigner series, such as “Poste Restante, Paris” by Alexei Tarkhanov and “The Sunny Shores of Genoa. Russian Happiness in Italian” by Natalia Osis. The locals in these books (as well as Russian visitors) complain about a large number of children of immigrants in European schools. I myself value Europe’s Christian heritage and its classical literature, which, unfortunately, it has long been difficult to teach modern English teenagers to appreciate. However, fencing the country off from refugees and immigrants is a dead end. Humanity's only chance for survival is social and cultural integration.

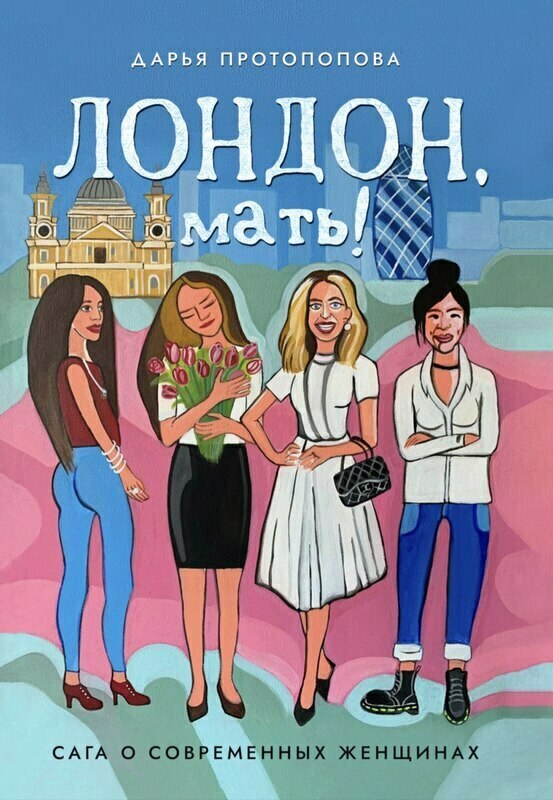

I’ve read ‘London, Mother***!’, your saga about modern women, and I liked the book. Your stories describe the lives of immigrants in the UK. What’s more, all of the main characters are women. Why is this?

In the subtitle, I state that ‘London, Mother***!’ is a book about women. It seems to me that life is more difficult for us than for men, even from a purely physical point of view; we have to deal with menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth, as well as often being forced to sacrifice our careers to raise children. All these problems are worse for immigrant women. Local men look at single foreign women with a mixture of curiosity, distrust and condescension, especially if they are from a relatively poor country. If your children are born in a foreign country, it is likely that your relatives are far away and there is no one to help you. Plus, women often choose the professions in which immigrants have the hardest time finding work.

Among your heroines there are women from Poland, Italy, China, Romania and Russia, but the only one to be tormented by nostalgia is a Russian woman, and her Russian husband has no feelings of homesickness at all. Is this an artistic device or are you drawing on personal experience? To what extent is nostalgia for the home country typical of immigrants?

This nostalgia is only typical of immigrants from Russia. It is a feeling of melancholy, and not simply a complaint about the lack of food from back home, such as the Chinese or the French make. Russians yearn not just for Russian dishes, but for the feeling that they are at home and that no one is looking at them with perceived contempt. Russians are terribly insecure people, yet at the same time, they strive to dominate (however, this may be due to their insecurity). Since the time of Peter I, it has seemed to us that we are doing everything wrong, that everything is better in the West, and at the same time we like to talk about how special we are and we say that our language, literature and music are better than those of other countries. But if we were truly confident in ourselves, we would not take criticism so painfully. My heroine was drawn home, to Moscow, because a British person was rude to her, and it seemed to her that this had happened because she was a foreigner. In fact, she had just stumbled upon a rude person, of which there are plenty in Russia as well. My husband is Italian, and if someone says something unflattering about Italy to him, he will simply smile, look at the offender with pity and go on secretly loving Italy and Chianti. Russians in similar situations become hurt and they begin to talk about the greatness of Russia until they foam at the mouth. We completely lack a sense of self-irony, and without this, it is very difficult to live in a foreign country. If we could laugh at ourselves, admit that we are not perfect and calmly love ourselves and others, the mysterious Russian soul would turn out to be ordinary, the same as everyone else’s.

One of your heroines wants to raise her child ‘not to be burdened, like her, with recollections and doubts about her own mindset and complexes, national or otherwise’, because it is easier for a person without roots to get off the ground. Is this about freedom or the influence of European ways of thinking?

This returns us to a favourite idea of mine, which is admittedly rather utopian; the abolition of borders between states and the emergence of a new type of status, the concept of being a ‘citizen of the world.’ This character wants her child to become the new Elon Musk, the conqueror of Mars. What kind of national borders can we have when people are colonising space, Google Translate is removing language barriers, and, via the Internet, you can meet people virtually who are on the other side of the planet? The variety of cultures, artistic traditions, cuisines, costumes and architectural styles in the world today all need to be preserved and protected, but I think people’s individual attachment to one country particular country or another is already a relic of the past.

All the couples that are described in the book are people who emigrated together. But one heroine is not married. Someone tells her that three million of her compatriots will come to Britain and she will be able to start a family with one of them, and she responds by calling the person who says this a racist. It is in fact true that many single immigrants look for partners among their own communities. How would you comment on this?

I would not say that single immigrants only look for partners among their own. Perhaps some do this for religious reasons, for example, amongst Orthodox Jews or more conservative Muslims, marriages outside the community are not welcome. There are girls from Russia who want to marry foreigners. But these stereotypes are crumbling in this world of social mobility and international education. There are more and more successful immigrant women who are looking for equality and partnership in relationships. When a woman is independent and is not traumatised from her experience of dealing with men in the past, her choice of a partner is no longer determined by his nationality. Alisa Zotimova's book, From Moscow to London describes the story of a successful businesswoman who chose a compatriot as her husband. For her, it was important to have childhood memories in common, like having watched Hedgehog in the Fog [a popular Soviet cartoon]. Others, in contrast, like exoticism in a partner. This is a very personal choice. As for my character's anger at being associated with immigrants from Hong Kong, here I tried to convey the feelings of a second-generation immigrant. People who were born in England to immigrant families find themselves in a special category; seen as not quite English in England, but also not quite accepted in their parents’ countries. Besides, of course, suggesting that a girl from Hong Kong is only interested in people of her own race is racism.

One of your heroines, an English teacher from Poland, works for a cleaning company. Is it at all possible to avoid such downshifting in immigration?

Of course, she could go on a teacher training course, and then work as a teaching assistant at a school or nursery. But the realities of London are such that it is more profitable to work here as a cleaning lady than as a teacher's assistant. What’s more, she has two children, so where can she find the time and money for additional studies or retraining? It is easier for a woman who is not burdened with childcare to find a job, even a job matching their qualifications. In any case, there are specialised jobs in demand that do not require retraining or the confirmation of your qualifications. Basically, these are professions where you can demonstrate your talent or skill: dancers, estate agents, graphic designers, fitness trainers and makeup artists, for example. In Britain, accountants, economists and lawyers all need to obtain local certificates and permits. It is difficult for journalists, but if they know English, they can work in international publications or retrain as translators. HR specialists, administrators and sales managers will first have to work in lowly positions in order to gain local experience before they can be contenders for their dream positions. It is always a struggle for writers and artists, whatever country they happen to be in, but migration enriches life with sharp new impressions and inspires creativity.

In your opinion, what difficulties do bilingual children face?

Children who are born after their migrant parents have moved to a new land do not face any language difficulties. On the contrary, they have an advantage over the locals. They naturally absorb not one, but two languages, sometimes more. It is more difficult for children with no English who come to Britain at, let’s say, the age of ten or eleven. If they go to an ordinary English school, then they are classified as EAL (English as an Additional Language) and they are treated as if they were deaf and mute. I saw this during my time working as a teacher.

How can an immigrant fit into British society? Is it even possible?

Joining society is an illusion. For example, while living in Russia, I didn’t feel like I was part of society at all, but at Oxford, I felt in my element. English society is like a stained glass window glued together from many small parts, and everyone decides for themselves where exactly they fit in. Public education and medicine are free here, for the rest you have to fend for yourself. The main thing is to find your niche, an occupation in which you can become indispensable. And the most important condition for a successful immigrant life is to maintain your self-confidence and a sense of self-irony. Remember that Britain is just a small part of a big planet.