On art walks Tatiana Vlasyuk has, without exaggeration, visited most of Russian London, and her Instagram account, @artwalk.london, has more than twenty thousand subscribers. The guide, a native of Moscow, attributes the popularity of her tours to her lack of a pre-prepared spiel. Instead, she talks, rather quirkily, about her passion, which is art, classical and modern. In an interview with the the head editor of Kommersant UK, Ksenia Dyakova-Tinok, Tatiana Vlasyuk goes through the reasons why it is worthwhile for business people and professionals to go to exhibitions, the right way to invest in art, what we can all learn from the frightening canvasses of Francis Bacon, and what the mysterious British cultural code all boils down to.

Modern business people have tight schedules making use of every minute. Why should they spend their precious time at museums and exhibitions? After all, they often leave feeling nonplussed, especially after seeing abstract or protest art.

In my view, art is the apotheosis of human activity. In this I agree with Tatiana Chernigovsky, who says that creative people help our civilisation develop. With their flexible mindsets they find new opportunities for growth, show us things that may seem paradoxical, and find ways for the human mind to unfurl from its chrysalis and take flight. Laypeople who do not think about art have a mundane approach to the world, they live in one place, surrounded by people they know and they fail to pay attention to many things, even if they are happening around them and are of critical importance. Art forces us to see unusual things, to leave our comfort zones and to be brought up to date, or even to be ahead of our time, as we take in creative energy. All visionaries, both in the business sphere and beyond, have worldwide perspectives, of which art is an important part.

Some people say that modern art is just a joke, a wind-up. Maybe it would be better to concentrate on the works of the old masters?

I understand this point of view. But, first of all, let’s look at the counter argument. In reality, modern art has become a higher form of marketing. It’s not so difficult to explain to people why they need something if they can actually make use of it, but it requires great skill to persuade them to spend huge sums on an unnecessary and impractical object the existence of which hadn’t previously even occurred to them. Top business managers have a lot to learn from galleries which display modern art and promote artists and new artistic trends.

Secondly, for me, modern art is my life. Our civilisation is now looking for new ways to express and present itself as the old ways are no longer fit for purpose. People understand classicism, and museums are full of it. This art was religious and did not reflect reality. It served the interests of a very small circle of the richest members of society and depicted their perception of the sublime. The problem of money and the artist has existed since the dawn of time. In those days, when they commissioned art, both the Church and wealthy aristocrats dictated what they wanted to see and how it should look. Only geniuses who achieved world renown in their lifetimes, such as Rafael and Leonardo, could allow themselves some freedom in their work. However, even they were obliged to keep their clients satisfied. Depicting reality accurately was central to this, and so gradually art became more realistic. For artists to achieve great mastery in realism required years of hard work. Just at the moment when the development of academies of art allowed any determined student to acquire artistic proficiency, photography appeared, making this effort for realism seem meaningless.

Today art’s global agenda has left the élite and started to live its own life, embracing a wider swathe of the masses who also want to be represented artistically. They want to be creative and they believe they have a right to self expression. That’s why modern art today is an enormous platform for pure, diversified creativity. I fully accept that 80% of it is rubbish which no-one will remember in 50 years. Still, these days, no-one will take it upon themselves to separate the chaff from the grain.

This is the legacy of the unfortunate experience of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period when brilliant artists were mocked and not given the recognition they deserved. Van Gogh suffered from cash flow problems. Gauguin, whose creativity gave birth to an entire new school of art, lived in poverty. The biographies of innovative artists teach us that it’s impossible to understand or foresee where artistic thought or European civilisation will take us. This is why a principle of the modern world is to let all flowers bloom, with no limits and full creative freedom. People depict the world however they see it and however they want. The resulting art may be either unoriginal and run of the mill, or exquisite masterpieces. Whatever creativity throws up. The only demand placed on modern art is to be original. Concepts shouldn’t be copied, instead our world should be constantly rediscovered in new ways. It really is a great space for experimentation. This is how it’s better to regard modern art. Getting to know it enables my clients to see something new. They sometimes get excited or even outraged as they start to think beyond their usual paradigm.

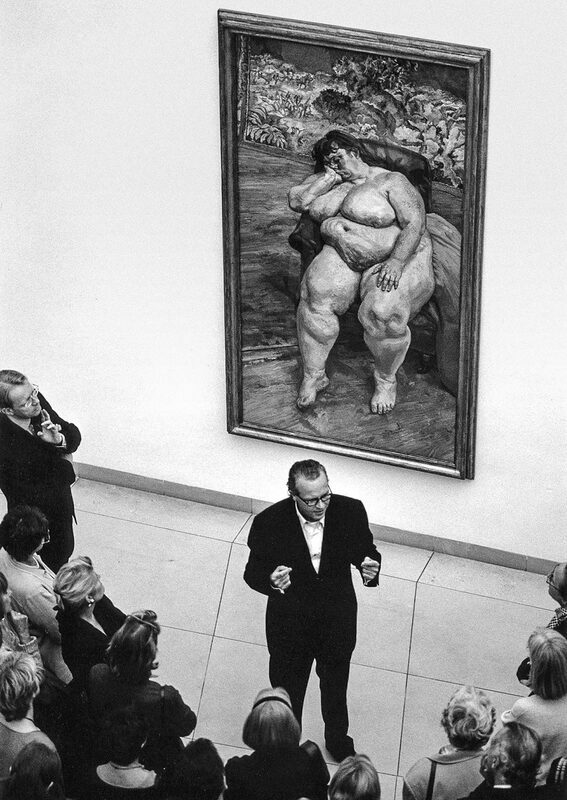

What could be more shocking, or even, in the eyes of a non-specialist, disgusting, than modern art? For example, why look at the picture Benefits Supervisor Sleeping by Lucian Freud if you can look at Botticelli?

I wouldn’t call the work of Freud, or of Bacon modern art. (An exhibition of Freud’s work is opening this autumn at the National Gallery, by the way). They are world classics, which are very close to us in time, it’s true, and of course, their work will live on for centuries. This is because their art turned a new page in culture and philosophy, as it incorporated the post-war European trend of existentialism. This movement was especially popular in Britain. The second world war shook the foundations of thought in Europe, leading to an identity crisis. Before the war, it had seemed that scientific and technical progress were an unequivocal good. It was believed that if everyone was fed, watered and increasingly prosperous, the world would become more harmonious and the people in it would become kinder. A clear and straight road to Heaven. It has to be said that this is more or less what actually happened in the post war period. It is undeniable that in well-fed, prosperous countries, the level of violence has fallen dramatically. However this civilising approach doesn’t take into account people’s contradictory natures, where the animal component constantly struggles against people’s spiritual inclinations, and it cannot explain why even wealthy people display the same unchanged instincts to kill, steal and rape. Why did the rich civilisation of Europe show the world barbarity on such a great scale during the two world wars? The philosophy of existentialism holds that people’s problems in life flow from human nature itself; from the recognition of the futility of existence and the need to find meaning in life, from free will, the need to make choices and the fear of taking responsibility for those choices. It arises from the fundamental indifference of the world and the necessity of interacting with it as well as from the inevitability and natural fear of death. But the more honestly we look at the world and the fewer illusions and unjustified expectations we have (especially about ourselves), then the fewer disappointments and less suffering we experience. For example, when we feel sadness we suffer and, at the same time, we look for reasons why life is punishing us. However, existentialism says that pain is an objective part of life. If people accept this they don’t waste their energy in needless reflection and instead direct their energy towards solving their problems. This makes them stronger, better grounded and happier overall. And of course, that’s not all…

Are you saying that Benefits Supervisor Sleeping is an idiosyncratic memento mori to remind us about the fragility and imperfection of life and human flesh?

Precisely. The artist Lucian Freud is trying to reconcile us to our bodies as his grandfather, Sigmund Freud, tried to reconcile us to our heads. The peak of physical perfection is a fleeting moment reached at twenty, when youthful bodies are resplendent. The human form is constantly deteriorating flesh. This is the way of things. The fewer neuroses people have about this, the happier they feel. In Britain this conviction is deep rooted. We can see how little the British are inclined to self adornment in comparison to Eastern Europeans, and how much easier it is for them to accept themselves as imperfect beings. For example, many women don’t wear makeup and don’t dye their grey hair. There is currently a fashion for healthy old age. For this we should be grateful to Lucian Freud, amongst others, as his once shocking pictures helped to ingrain the acceptance of imperfection and ageing into the minds of the British people.

Does this mean that going on an existentialist art tour can help you to learn more about Britain and the roots of the modern British world view?

Of course. Why are Lucian Freud and Bacon geniuses? Because they saw which way the wind was blowing before other people had taken the time to reflect. These days artists no longer depict the world around them as they prefer to concentrate on what is inside. A turning point was the appearance of surrealism in art with André Breton’s manifesto in 1924. Breton, drawing on the work of Freud grand-père, announced to a surprised humanity that, in addition to consciousness, people have a subconscious in which good and bad coexist, roiling and seething, and sometimes bursting out in foul miasmas, which are expressed as harmful behaviour. The main idea of surrealist artists was to expose and portray all this. (By the way, the Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition has already opened at the Tate Modern).

Can we get ideas for business at exhibitions?

Of course. It is always good for business people to understand properly the world we live in. Knowledge of history and culture can help us to structure the future. Naturally, it’s difficult to do this for the long term, but there are people who feel these things.

The second practical application of art for business is investment. But, as I have said, this is not so simple for modern art. It is impossible to distinguish broad cultural trends when you are in the middle of them. Of course, some galleries offer analysis and explanations of the works of modern art they sell, but this is a lottery. I usually advise clients who buy modern art to select works which they like and seem essentially original. At least that way they will make their lives more beautiful. If this art grows in value, then that’s a pleasant bonus.

For investment purposes, it’s better to minimise risks, so I’d recommend buying the work of recognised masters. Although unfortunately, these tend to be already quite expensive, they are sure to grow in price. However they have become ‘blue chip’ and there are never very many of them. If you buy a work by Bacon or Freud, or even more so if you buy something by a renowned modernist like Manet, you can rest assured that your grandchildren will thank you for it.

But what should a mere mortal do, who hasn’t got the millions to buy ‘something by a renowned modernist like Manet’?

Now people without great means have the opportunity to participate in schemes set up for the purchase of specific paintings. These are aimed at large groups of people, from a hundred to a thousand. I think this idea has great potential. Usually these joint purchases are kept in special storage facilities, or are even put on display in museum exhibitions. Incidentally, it is a very interesting recent trend among collectors to allow their paintings to be shown in state museums such as the National Gallery in London, where they will be seen by visitors, be well looked after, get into all the catalogues and be seen at various exhibitions…this helps the value of these works to grow further. At exhibitions both in London and worldwide, we see that, increasingly, the paintings have been brought in from private collections. Although this is not an entirely new phenomenon, previously it happened to a much lesser extent as the pictures’ owners used to worry about the safety of their property while not really seeing any benefit from their works being on public display. Now, however, alarm systems have become more reliable, the logistics are easier, and exhibitions have grown in popularity.

How should newcomers to the art world go about visiting exhibitions if they want to get the most out of it and learn more? Apart from the Surrealists, what else is coming up soon?

I strongly recommend going to exhibitions prepared. It’s best to go with a guide. If you don’t have one, it’s best to read descriptions of the works and have a look at the catalogues. In Britain this information is freely available. I would visit practically all the exhibitions put on by the National Gallery, the Tate Modern gallery, the Tate Britain art museum in London and the Royal Academy of Arts. 2022 will be especially rich in this regard because the exhibitions that were delayed by Covid will finally take place. For example, Rafael is coming to us; there will be an exhibition examining all the works of this genius of the high renaissance. It was supposed to open at the end of 2020, to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death. His paintings are considered the gold standard of the classical western cannon, and many generations of artists have been influenced by them. He was able to discover and visualise the components of human beauty, and to find the point of harmony, combining animal and spiritual natures. His perception of the world has entered into human consciousness, whether we recognise it or not. This exhibition is a must see.

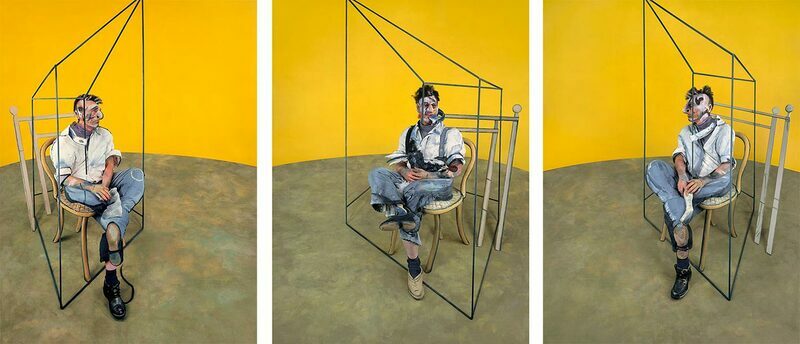

This autumn you must go to the Lucian Freud exhibition which we have talked about. Also, of course, Francis Bacon is waiting for you, there is an exhibition opening at the Royal Academy on the 17th of April. Nobody can convey humankind’s terror of our own frailty and mortality better than him. For me, Bacon is a genius, although there is no more terrifying artist in the world. His imagery demonstrates how much pain and suffering we hide inside, it is as if he is saying with his work, ‘don’t be afraid, you’re not the only one, we all feel this way’.

What is the difference between your tours and those conducted by museum guides with blue badges?

The blue badge means that the guide is in the union. A licence is not necessary to work as a guide in the UK, anyone can do it, as long as you have something to say and someone wants to listen. In continental Europe, guides must have licences, however. (In Russia, from the 1st of July 2022 a new law will come into force requiring tour guides to have accreditation and also forbidding foreigners from working as guides or interpreters, except for citizens of countries having special agreements with the Russian Federation). But it is also important to realise that in Britain, guides with blue badges have privileges. Only they have the right to take groups inside the main historical attractions such as the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey etc. This, of course, is the largest tourist market. But these exclusive privileges do not extend to tours of the city streets or art museums and galleries. I am not especially interested in doing standard tours and telling people about long passed days. I feel closer to contemporary Britain and its culture in the broader European cultural context. And of course, my talks differ markedly from those of guides with blue badges. All my tours are tailor made and personalised. In my city tours, for example, I study practically every house, take into account every plaque and investigate every architectural feature. Then I find the details I need in books and other sources. The result is a deep immersion into the cultural context of the locale.

I am an eternal student. I have studied all my life, I have several university degrees in different areas; technical, economic and business related (I did my MBA in Russia), as well as in art (I studied the History of the Arts at the Russian State University for the Humanities and did my Master’s in the Art Business at Sotheby’s in London). I understand that my clients are not only tourists who have come for a couple of days and want to see the main historical attractions (the guides with blue badges are for them). My clients are local residents and anglophiles on the same wavelength as myself. They are people who want to know how this country works and understand its worldview from the inside, through its history and culture. This is almost like conducting anthropological research. As all countries are different, it’s always interesting to do this. What makes people different here? Why do people in Russia react to certain stimuli in one way, while in France or Britain, they react differently? What makes up the cultural code which gives rise to these differences?

You describe the local cultural code from several aspects. What needs to be taken into account?

When I was studying for my Master’s at Sotheby’s in London we had a wonderful lecturer in international law. Our teacher wanted to drive into our heads the idea that the world is divided into two parts; the Anglosphere and the Francosphere. The Anglosphere is all the countries that grew from the British empire, its former colonies etc, what is now called the Commonwealth. And of course, the USA, which was partially built in the image and form of Britain itself. The Francosphere is France and what grew under French influence in continental Europe. Russia long spoke French, and the country’s law and approach to life comes from this tradition.

What’s the difference? In England, everything is permitted if it is not expressly forbidden. In continental Europe, it is forbidden to do what is not expressly permitted. It would seem that this is no difference at all, but in fact it is significant. Britain and the Anglosphere is not inclined to create bureaucracy. The role of the state is minimised and regulated. Things predominantly work on trust, without much help or hindrance from the state, although there is always a drive to support business. In Britain everything works thanks to private initiative.

In continental Europe the bureaucracy is very strong, every action requires paperwork and instructions. This process often gets out of control, overstepping common sense and private initiative.This is why the institutions are especially important; parliament, the presence of civil society, and an independent press, all of this seems to compensate for the birth defect of this civilisation. And as soon as these institutions start to fail, the catastrophes begin.

In Britain there are other problems. Here the state tries not to overstretch and perform unnecessary functions (this is why it was so difficult for everyone at the start of the pandemic). Even natural monopolies are structured so that as much as possible is in private hands. This means that at times, Britain loses out when the state, in the name of the nation, organises the common good. For example, things are frankly rather bad here when it comes to health care, and public transport is very expensive.

Both models have their pluses and minuses. I feel closer to the British model. This is because I like to be given respect and just left to get on with my life and do my work how I want. I may not get any help, but nor do I suffer from unwanted interference.

How were the last two years for you? After all, the museums and galleries were closed for a long time…

In the first lockdown I was actually quite glad to have a break and do some of the things I don’t usually have time for. These were mostly things like devising new tours, working on my instagram page and talking to my colleagues all over the world. I shot live footage of an absolutely deserted London. Believe me, I felt such strong emotions! I’ll never forget the experience.

Between lockdowns, I offered walking tours around the districts of London for small Russian speaking groups, and this format, incidentally, proved very popular. But I had to raise my price a little. I thank my local clients who were understanding about this. I have kept this small group size (up to eight or nine people). It seems that everyone likes this format.

Until recently, my favourite museums have been under pressure. Only in September 2021, after being practically banned for a year and a half, was I allowed to take tour groups to them. But for a time I still didn’t take so many groups to museums. I didn’t want to take any chances, as I saw there were still a lot of people with Covid. I offered more outdoor tours, in the fresh air, and put on an extra few walking tours.

Now that all the restrictions have been lifted, I am starting to concentrate on museum and exhibition life once more. So let’s go and see some art!