We continue our three-part look at the peculiarities of the British way of handling pregnancy and childbirth. The first article dealt with the standards and procedures of antenatal care. Today, we consider childbirth, the second stage on the path from conception to parenthood. In a departure from conventional editorial practice, this article does not feature commentary from mothers. We have taken this decision because women’s feelings during childbirth are highly personal. For every account of a birth that, subjectively, went well, another, more negative story can be found. These negative impressions often leave a stronger mark on people’s memories.

So, after 280 days of gestation, the long-awaited due date comes, a day which has been both longed for and feared, on which something can always go wrong, however well a birth is planned.

Statistics and facts

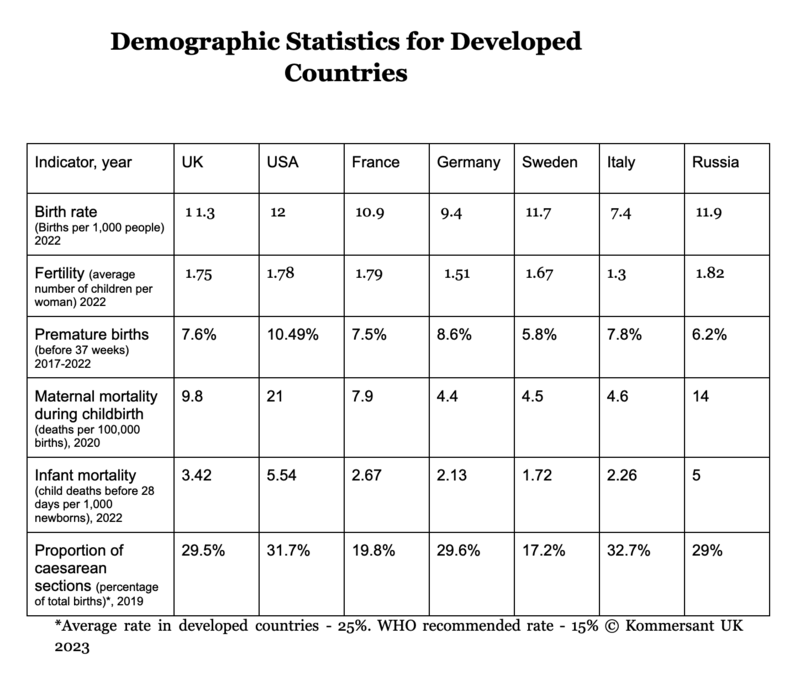

Around 90% of births in the country take place in the maternity wards of NHS hospitals, 4% in private wards and clinics, while 2% of women give birth in familiar surroundings at home (the remainder of births occur in birth centres and other unpredictable locations). Statistics from recent years show that only slightly more than half of births happen naturally; the number of artificially stimulated inductions grows from year to year, as well as caesarean section operations. This means that in 2019, almost 30% of newborns came into the world via either planned or emergency caesarean section.

The proportion of premature births, after a gestation of less than 37 weeks, is around 10% globally. In England and Wales in 2021, 7.6% of all childbirths were premature. Every 65th pregnancy was multiple, so, in Britain in 2019, 10,757 twins and 156 triplets were born.

The busiest day in maternity wards in Britain is September 23, with October 7 in second place. Over the last few decades, the commonest birthdays have been from the end of September to the beginning of October. This is not just a curious fact; at this time, maternity wards are at capacity, and pregnant women need to be prepared to wait longer than usual for their customary examinations, and entire maternity wards may be full. Water birthing pools, especially, are likely to be unavailable.

What is different about childbirth in Britain?

Although the physiological process of bearing children is the same the whole world over, British rules and protocols feature peculiarities a little different from those generally held in the Post Soviet Space.

Here, for instance, no one will come to take a woman about to give birth to hospital in an ambulance. If there is a suspicion that labour has begun, women have to travel to the hospital independently. What’s more, if a future mother comes early, before the cervix is dilated to four cm, she may be sent home, irrespective of any pain felt during contractions.

It’s better to choose a hospital and record your preference in your maternity notes. Usually, up to 38 weeks, you can change your mind, although it’s true that considering the different record-keeping systems, more time may be needed to make a note of the change. Tours of all maternity wards are available to women to help them make this choice (these tours are organised on specific days).

Before going to hospital, there is no need to shave intimate areas. Nor is this done by staff on arrival.

Here, the presence of birth partners is encouraged. Two of these partners are allowed, who can stay in the ward throughout childbirth, even without sterilised gowns. Only one partner is allowed into the operating theatre, however.

In birth plans, which a woman includes in her maternity notes, usually her wishes are shown in advance, including her preferred delivery location, pose during birth, permissible medical interventions, as well as other issues such as who will cut the cord and whether she would like the baby to receive vitamin K.

Although it may seem strange, births at NHS hospitals may be attended by the same specialists, the main difference comes down to having a separate room and the presence of the midwives who accompanied the pregnancy (although doctors are not always present at privately organised births either!)

Where are babies born?

In Britain, women can choose where to give birth, whether at the labour ward of an NHS hospital, a birth unit at a midwifery centre or in the comfort of their own home.

Home births are available to women who have previously given birth after a normal pregnancy and have no risk factors such as a previous caesarean section or premature birth, or high blood pressure. Home births are attended by one or two midwives from the community midwife group, who will already know the future mother. Being in familiar surroundings is a significant factor that can have a positive effect on the process of giving birth. The only anaesthetic that can be offered is laughing gas. The midwives remain with the woman throughout childbirth and for an hour afterwards. If any problems occur, they will organise the woman’s transportation to hospital, where all examinations of the newborn take place. The midwife will come to see the mother and baby the next day.

Two-thirds of hospital maternity departments in the country have midwifery departments. They are also called home birth departments, as their main idea is that childbirth is a natural process with its own course rather than a risk-fraught event in which every step must be controlled and micromanaged. Interiors here have a domestic or hotel-like feel, with wide beds, subdued lighting and music. There is a birthing bath and various kinds of equipment to facilitate labour, such as an exercise ball and a special chair. In these centres, there is space for birthing partners to sleep. The only anaesthesia available is laughing gas, epidurals are not done here. If a woman has no risk factors, she may have her birth at a midwifery department. However, if any arise, she will swiftly be transferred to a maternity department (these are often located on different floors of the same hospital).

The overwhelming majority of children are born in the maternity departments of hospitals. In them, everything is standardised and unified, although differences in equipment and the types of epidural provided exist. In maternity wards, the presence of a birthing partner is encouraged, whether this is the father of the child or another close friend or relative, but there aren’t any especially comfy chairs for taking naps. Baths for water births are not always available. Most likely, there will only be one toilet and shower for every two maternity wards.

Stopwatch at the ready

From the onset of labour, everything for the woman giving birth revolves around two objects; a stopwatch and a piece of paper for writing down intervals between contractions. A bag for the maternity ward should already be prepared. The right time to go to the hospital is either when the contractions become regular, at three to four-minute intervals, or when the waters break. To be on the safe side, it’s better to call the maternity ward’s hotline in advance to be sure that they won’t send you home on arrival.

When the woman has arrived, she goes through an initial assessment or triage. Cervical dilatation is checked and basic assessments are made, including listening to the baby’s heart, after this, the woman is sent to a maternity ward where she is observed by midwives. There is a button for calling medical staff by the bed. If the woman has been prescribed a planned caesarean or induction, of course, she will go to the hospital at the appointed time.

From then on, each woman’s situation develops differently. Births are attended by midwives, when necessary, an anaesthetist or obstetrician is called.

Gas to tame the pain

In 2019, The NHS conducted a survey of women in England who had just given birth. A third of respondents had used natural methods of pain relief such as breathing, massage and hypnosis and around two-thirds received anaesthesia via pain relieving laughing gas (gas and air, or Entonox), however, almost no women limited their pain relief to gas alone, as around 30% also received an epidural, while 15% used a TENS machine. Some women could not be anaesthetised for medical reasons. 4% reported that anaesthesia was completely unavailable to them, while every fifth woman received no pain relief as it was already too late to administer. These figures tell us that it is worth considering pain relief beforehand; it’s better to stock up on an affordable TENS device, as well as researching breathing techniques and other methods of pain relief.

The contentious c-section

Caesarean section remains a controversial subject on women’s forums, as, according to the proponents of this operation, it allows a high degree of control over the situation, as total pain relief can be administered without interruption, whilst also reducing the danger of injury during birth to babies. In the British setting, another, not insignificant point is that a caesarean is done in the presence of a doctor, which does not usually happen in the course of conventional childbirth. However, overall, the statistics show that women recover from these operations more slowly and with greater difficulty than from natural births, they may find initiating breastfeeding requires more effort, and their babies are more likely to have breathing problems during their first days. What’s more, a range of research has shown that natural birth plays a significant role in the formation of a healthy microbiome in the child’s gut, which in turn affects the work of their immune system in future life.

In recent years, women’s birth preferences in Britain have received more attention and those who voluntarily opt for a caesarean are more likely to get one. However, if there are no medical indications for the operation, they must justify the decision. (A c-section is more expensive for the NHS than a usual birth). The preponderant opinion in Post-Soviet countries that, once a woman has had a caesarean, she should always have caesareans is not held by the medical authorities in Britain. On subsequent pregnancies, a natural birth may be recommended (a Vaginal Birth After Caesarean, or VBAC).

Twins, triplets and more

On average, 14–16 out of every 1,000 British children are born as a result of multiple pregnancies. This figure has grown in recent decades as a result of the adoption of IVF and the rising age of the average mother. Women expecting twins or triplets are paid special attention during pregnancy and birth, and more than half of twins and almost all triplets come into the world via caesarean section. More medical staff are usually involved in multiple births; for each baby, three specialists are required; a midwife, obstetrician and paediatrician.

Partner, Protector and Pathfinder

A birth partner is someone who a woman trusts to be present at the birth of her child. Almost all women in Britain come to the maternity ward with a partner; often this is the father of the child, but not always. Increasingly, women and their partners call on the services of a professional assistant, or doula (this person may replace the father at the birth). These specialists first appeared at the turn of the century and now, 20 years later, more than 650 certified doulas work in Britain; in 2021, they assisted at the births of more than 3,500 women.

A doula is an experienced guide to childbirth who knows all the ins and outs of the physiological processes women go through at this time. They know the NHS regulations, have seen many births and understand when support is especially important and how to speak to medical staff. Some doulas have qualifications in medicine or psychology. These specialists help prepare women for birth by keeping them informed. They teach meditation for pain reduction, they can massage numb backs and explain what is happening at any moment of labour in accessible terms, all of which helps to reduce stress. Most importantly, the doula is with the woman throughout labour. They also meet her a few times before and after the birth.

‘NHS professionals have the expertise, but, firstly, their roles are severely limited by the regulations and secondly, midwives just don’t have the time to dispel fears, tell women how to breathe right or how to prepare themselves mentally’, says Yulia Prokopchuk, a doula from London. ‘We become the bridge between the woman giving birth and the medical staff and other people present at the birth. We help with translations, either of medical language, or, when necessary, from English into Russian, and we make sure that the woman’s wishes are not being ignored. We give her physical, emotional and psychological support’.

Research has shown that psychological support helps to reduce postnatal depression, especially now, in these times of social networks which often create unrealistic expectations of pregnancy and early motherhood.

Midwives regard the presence of doulas during labour positively, admitting that, sometimes, they don’t really have enough time to pay as much attention to women as they would like. ‘If a woman receives more support, if she can use non-medical pain relief or is advised on the best pose to reduce pain, then that is always beneficial’ says the midwife Natalija Kolesnikova, the mother of six children. ‘However, a very important issue is the communication between the midwife and the doula. Sometimes the doula is not regarded as a professional, which can lead to tension. Mutual understanding and cooperation are necessary to achieve good results’.

Doulas meet pregnant women several times before the birth and are with them throughout labour and childbirth. Postnatal Meetings are necessary to help with breastfeeding and to give emotional support. Each doula works differently, offering a different number of meetings and a different range of services. Yulia Prokopchuk’s standard fee includes eight antenatal meetings (ideally, starting from the 25th week) and one or two postnatal meetings. Consultation by telephone is available for two weeks after the birth. Her extended package includes a postnatal massage session and other procedures to help assist the woman’s psychological recovery.

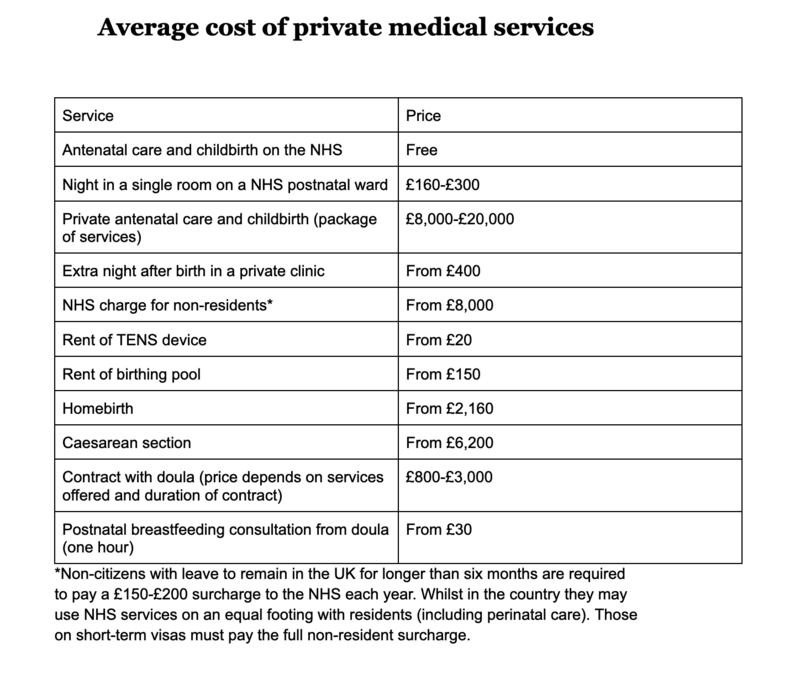

The services of a doula are not cheap; a qualified and experienced specialist charges from £1,500 to £3,000 for a contract (novice doulas charge less), but this is incomparably less than the cost of a private birth. This is why these services are called a “luxury for the middle classes”. The full list of doulas registered in Britain can be found on the site doula.org.uk.There are around twenty certified Russian-speaking doulas in the country. Several of them have come together in the mamam.uk project, as part of which they give women useful advice for free. The Instagram account of the same name has live streams, publishes advice and puts on question and answer sessions, as well as organising free monthly meetings in London where they discuss issues affecting pregnancy and birth.

Is having a birth privately worth the money?

Fees for private healthcare provision during pregnancy and childbirth are not insignificant (see the table below). On the NHS, by contrast, it’s free. What are women getting for their money?

Amongst the advantages of having a birth privately are more tests and more attention during pregnancy, accompaniment by the same team of midwives and obstetricians throughout and a better ward with a personal bathroom and more comfortable conditions for partners and visitors. In theory, it’s possible to pay for some extras at NHS hospitals, such as a separate room on a postnatal ward, but it’s impossible to arrange this in advance and the room may be full at the moment when it is needed. After her first birth in a ward for five people, one young mum shared a lifehack; if a pregnancy has no risk factors, it’s better to give birth in a midwifery department, as they have huge rooms with two-person beds where the conditions are like in a hotel health spa. They are equipped with everything necessary for the process of giving birth, but it’s all hidden away to avoid creating a clinical atmosphere suggestive of an operation. The result is a calming ambience. The woman and her partner can stay there after the birth until she is discharged.

At private maternity homes, antenatal wards or pools will be reserved for the patient. However, in an emergency, the woman may be swiftly transferred to an ordinary hospital, as all the equipment necessary for difficult births is found there, as well as the intensive therapy department (according to the statistics, only around two-thirds of women give birth where they initially planned).

On signing a contract, many points are worth checking, such as if payment of the doctor and anaesthetist is included, what anaesthetic will be used and at what cost and also how the stay in the ward after the birth will be paid for; it may turn out that all these services will later be included in a separate and rather sizable bill. Pregnancy care from an obstetrician in a private London clinic costs £6,500 from the twelfth week of pregnancy, £5,500 from the 28th week and £5,000 from the 32nd week. Usually, a downpayment of 50% of the fee is required on signing the contract with the remainder to be paid at the 36th week. In some private hospitals, the cost of the contract does not depend on the stage of the pregnancy. Signing a contract for private healthcare can be done at any point, even the very end, but, critically, it must be before the 38th week. The fee to have a consultant present at natural birth is £6,300, and £8,000 at a planned caesarean (in both cases, this does not include remuneration of the consultant). A contract for private healthcare may be annulled, but a penalty must be paid to do this. Precedent shows that clients who leave private medicine for the NHS cannot return to a private contract.

Prices for private healthcare are such that the overwhelming majority of children in the country are brought into the world under the care of NHS specialists, despite the deepening crisis in the sector. The good news is that the services of private healthcare professionals can be used to complement state provision. Midwives affirm that during labour, all women, regardless of whether they have paid, receive the same treatment. NHS surveys show a rather high percentage of new mothers give positive feedback about their experiences at NHS hospitals (72% according to a 2022 survey). One woman we talked to told us that she considered the decision to go private at length, by asking acquaintances, reading reviews on forums and weighing up all the variables and the risks before choosing not to pay. In the end, she had a better experience of childbirth than her friends who had signed £20,000 contracts. This is why many decide to stick with NHS care whilst supplementing it with a range of tests and checkups done privately (see the previous article to read about the additional private testing available during pregnancy).

The next article will deal with the British approach to the care of newborns in the first few days of their lives.