Record-breaking heat, drought and fires in Britain and other European countries, as well as the abnormally warm autumn this year, have forced even the most inveterate sceptics to think about the reality of the climate crisis. Hiding under a blanket is getting increasingly difficult. Meanwhile, dramatic rises in energy costs are not just hitting Britons’ savings, but also endangering the newly formed green consensus to achieve carbon neutrality. Even King Charles III, a long-standing supporter of these ideas, was forced to forego participation in the COP27 climate forum. This is due to be held in November. Whether Rishi Sunak will go is still unclear. Although the premier has already announced that he won’t go, maybe he will change his mind under pressure from his MPs.

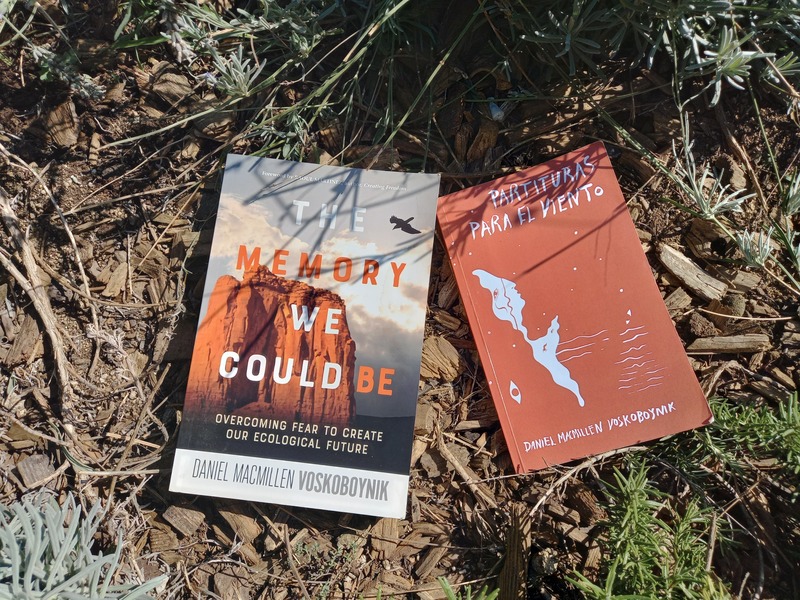

Dan Macmillen-Voskoboynik is a young eco-activist with Russian roots. He is a Cambridge graduate and the author of an incisive eco-poetical book; The Memory We Could Be: Overcoming Fear to Create Our Ecological Future. He told Kommersant UK why humanity now finds itself in such a deep environmental crisis and what we can do to get out of it.

Why did you write this book and who is it for?

For me, ecology has never been a far away topic, removed from my everyday life. I have already been working in the environmental human rights movement for more than ten years (in different organisations and countries, from England to Argentina). I started off with more official and larger organisations, doing ecological science and I was struck that, for society as a whole, ecological topics seem very far away. The mainstream view of the ecological movement is that it’s a small, marginal part of society which just likes to do recycling, sort of like modern hippies. For me, the environmental movement is promoting a certain paradigm and offering a deeper perspective on the world while re-appraising society’s place in it. Ecology is everywhere; we can’t live in isolation. The first principle of ecology is that quality of relationships affects quality of life on a very global level. I wrote the book The Memory We Could Be with the aim of enlightenment. Most people still don’t understand that ecology is about them, rather than about far-off places. This is especially true for discussions of climate. I also tried to write a text which would be easy to read; an ordinary person doesn’t have the time to read scientific works and follow lectures about the climate. I wanted to explain the topic in simple or even poetic language.

To take an analogy from family relations, how would you describe a modern person’s relationship with nature? Are we like abusive teenagers, who beat their mothers and take everything they need from them? What’s the diagnosis?

Actually, it’s not quite like that. The diagnosis is a complete disconnection. An absence of any relationship at all. Worst of all, many do not understand or do not notice, that we are part of a wider web of life, a network of ecological relationships. And this happens because of how we’re brought up. We think of nature as something separate, something far away, which must be preserved or defended, while not recognising that we ourselves are part of it. For me, it’s very important to show people that we, and all our works, are part of nature. It’s very important to bridge this gap. The harm that we are causing to nature is, first of all, the harm that we are causing ourselves. Ecological activists, often from rich western countries, tell stories about faraway places; somewhere in the Amazon or Siberia there is a crisis going on, so let’s do something about it. However, ecology is a gauge which can be used to watch the whole world at different scales, starting with our own bodies. Our bodies are part of nature, they are extremely complex aggregations, starting with the cells and bacteria. To survive we need very many things; food, water, air and space of our own. We don’t live in a vacuum, instead, we all exist within a web of relationships.

Why do so many people affirm that they love nature, buying dachas [summer houses- translator’s note] and cottages near forests and lakes, yet remain convinced that it is impossible to live without oil and gas? In their opinion, the oil and gas economy is like capitalism; a bad system, but the best available, as there’s no other choice. They are annoyed by Greta Thunberg and the so-called green lobby, which, among other things, they accuse of seeking personal enrichment. What would you say to people who have this position?

The problem is that there is still no one overarching environmental agenda. But our world is very complex; it’s not even just more complicated than we think; it’s more complicated than we can imagine. Just as we have many ecological systems, there are a great many forms of political environmentalism. A wide range of positions exist. I can’t justify or even imagine the views of everyone who calls themselves an environmentalist, as environmentalism is a broad church. We can’t say that all environmentalists think the same, or that their opinions are all based on sound scientific research. When people suspect that there is a commercial interest, they are right; there is one. Many brands are using greenwashing to give the public the impression that they support green ideas and that they are for sustainability. But, at the same time, the most profitable industries in human history are still those involved with the extraction of coal, oil and gas.

For the last five centuries, those in power have been directly involved with pollution. The countries that today are the richest are the very ones that have polluted the most over the last few hundred years. There is a link between industrialisation, colonialism, pollution and wealth. When people accuse China of causing all these ecological crises, it’s worth remembering that China is, in a way, the kitchen of the world and that over the last 20-25 years a lot of waste has been sent there from Europe, Britain included. The Chinese economy also produces a lot of waste, but from the perspective of western countries, it is unfair to blame the Chinese alone for global pollution levels. Many polluting industries have been moved from Europe to China, so we have to share that responsibility. Emissions from the production of the coffee that we are now drinking in London would usually be counted as released by Vietnam, Columbia or Brazil. It’s easy to point a finger at developing countries and blame them for everything. However, the average inhabitant of India produces several times less waste and emissions than an inhabitant of Britain. The pollution from a resident of Mali is three hundred times less than that from a typical American. You can’t even compare it!

We have to seek answers from history to the question of why we are in this situation. The first place to look is at colonial history. Many people are genuinely surprised because the media don’t tell you this. Everyone knows that we’re in a crisis, that it’s a disaster, but no one explains how we got into this mess. Without a historical understanding of the climate crisis, people lose track of the scale of what’s happening and start to think that micro-individualised solutions might be enough. People think that in order to overcome the crisis, they should recycle, become vegetarians and switch off lights, but in thinking in this way, they are concentrating on the present while ignoring the legacy of the past. No one is trying to focus on the political agenda because, if they do, the west doesn’t come out in the best light. The status quo, our ecologically harmful way of life, has become normalised; we think the endless consumption of energy entailed by the intensive use of cars and electricity is normal. The world could be organised in many different ways, but we have come to arrange it in this way, and we’ve been sustaining this system for 150 years. It’s difficult for us to imagine anything else, but we have to, because, at the very least, our life expectancy depends on it. If it wasn’t for pollution, people could live a lot longer. For example, almost half of school children in New Delhi develop lung damage due to air pollution.

What about the widespread developmental disorders among children, for example, autistic disorders and hyperactivity? Many scientists also attribute these to polluted environments in industrial cities.

I am not an epidemiologist, but there is research showing that polluted environments affect many functions of the body and that there is a link between environmental pollution and neurological and respiratory problems. In their book, Inflamed, Rupa Marya and Raj Patel compare inflammatory processes in the body (for example the development of cancer cells) to the ‘inflammation’ of the world caused by the numerous forest fires which are burning right now. It’s a very beautiful and apt analogy. Usually, when we think about health, it seems that everything depends on our lifestyle and preferences, but we live in society. I don’t choose to breathe the dirty air of cities, yet I had no choice. This means we need to take collective decisions about this. As Kavian Kulasabanathan says, we must oppose the systems of sickness. Doctors often say that health begins at home; if you live in a building with good ventilation, heating and a good bed, if you have the money for medicine and high-quality healthcare, then your health will certainly be stronger than that of those who live in cold and damp housing, sleep on the floor and only seek medical attention in cases of dire necessity.

Recently, it’s been in the news that the main cause of legionnaires disease in Britain is poor ventilation in residential buildings.

This is true. Ecologists are the ones who examine these links. For example, the welfare of your home depends on many things: the quality of the building, your salary, and the stress that you feel. This is why I begin with the idea that the first ecological system is the body. The space we inhabit is our second body. In many cultures, there is simply no understanding of this.

This brings to mind a famous quote, I think it was Michurin [a famous Russian agronomist- translator’s note] who said it. He experimented a lot with plant selection: ‘We cannot wait for favours from Nature. To take them from it – that is our task’. This attitude is consumerist, even though the Soviet Union wasn’t a capitalist state. How do you explain why this attitude has become so ubiquitous?

This school of thought is called extractivism, and it views nature as a resource. This resource must be optimised and exploited, as efficiently as possible. Soviet power was competing with the capitalist world, so it was important to demonstrate that the USSR could do everything much quicker than they could on the other side of the iron curtain. Again, there is an obvious link between the exploitation of nature and of people; in labour camps, prisoners worked without breaks.

But how and why did the environmental movement come about if it was not in the interests of states? Is it because a transition to a digital society has occurred? What changes allowed the movement to arise?

The usual answer of mainstream environmentalists is as follows; it all started a hundred years ago in the west, in the US and Britain, when certain enlightened individuals began to think ‘how terrible; we’re polluting the earth!’ I don’t agree with this view. It all comes down to the activation of biocultural memory. Humankind has been around for hundreds of thousands of years, and over these millennia we’ve built up a memory of how to live in different regions and of how to survive in especially extreme conditions. For example, the indigenous people of Chukotka’s knowledge of how to live off the land there is their social and cultural heritage. It’s widely held that humankind is the enemy of nature and that wherever people set foot, they destroy everything. But this is wrong. Much research, in regions such as the Amazon, which is now one of the most biodiverse places on the planet, has looked into how the natural environment has changed due to human activity. You can take a map and seek out the areas with the greatest linguistic and cultural diversity and then, on the same map, find the places that stand out for their high biodiversity: Australia, Columbia, DRC, Brazil, and Russia. People believe that the best way to protect nature is to create national parks and reserves which no one will visit. But the best-protected forests in the world are those inhabited by indigenous people because the locals know how to feed the land they live on. Over recent centuries, there have been policies of repression of indigenous peoples, but now scientists understand that the knowledge of these people is just what might save us. These are the people who know best how to preserve the balance of the land, as they have not only protected nature but also improved it.

Maybe there are just too few indigenous people and they haven’t spoiled anything because their populations are insignificant?

The fact is that indigenous peoples make up five per cent of the population of the earth. 25% of world ecosystems and 80% of world biodiversity are found on their territory. Of course, lumping all indigenous people together in one category is meaningless as they are pluralistic societies with a wide range of different traditions. But the knowledge and learning of these societies is priceless, especially right now. We all know the word ‘taboo’. In Fiji, it was forbidden to catch fish in sites where they spawn, and these places were known as ‘taboo’. We now understand taboo to mean some kind of limitation. Ecology is also connected with certain limitations. We live in a society where we have the opportunity to do anything we want. But having limitations isn’t negative because they allow us to flourish and be creative.

What taboos do we need the most urgently? Which would you introduce if, say, you became prime minister of Britain? Or what taboos can people prescribe themselves?

This question itself: ‘what can I do personally?’ elicits many answers. Of course, you can do an awful lot off your own bat. But you could ask a different question; what can we do together? We do live in a very individualised world where we are always told that everything depends on us personally. But we can only save the planet collectively. We need a system of limitations. For example, the working day is very important. In the past, people worked seven days a week, without days off, then the working week was shortened to six days, and then to five. Now people often discuss the need to go over to a four-day-week, and this has a host of ecological advantages. We should understand that time is truly important. For example, to reduce your carbon footprint, it’s better to travel by train than by plane, although it takes more time. However, if someone has more free time, they might opt for the train. In a society where a lot of time has been freed up, people can spend more time with their families and friends, do sport and be creative. Now society is organised to maximise work time and productivity and these things are far less important. Increased free time would help people to do things which are ecologically significant; planting trees, for instance. Here is a simple example: if you’re short on time, you might go to a restaurant and buy a takeaway meal in a plastic container, but if you have the whole day free, you’re more likely to cook yourself dinner at home. The more time we have, the more opportunities we have to take decisions, study, read, live and do many other things. The second taboo is the use of fossil fuels.

Currently, many countries, such as Britain and Germany, are restarting decommissioned coal-fired power stations. A green agenda, it seems, has only just come about, there has been a lot of talk about achieving carbon neutrality, and now, because of the military action in Ukraine, everything is going backwards at great speed. What do you think about that?

Fossil fuels are an undemocratic form of energy. It is a concentrated form of power, chaotically distributed around the world. It gives Russia, Qatar and the Emirates tremendous influence, but this is down to geographical chance, and, incidentally, it doesn’t help a country develop very much. Fossil fuels are, in essence, very easy money. They give rise to corruption. There are many reasons why the energy system must be reformed; both social and environmental. It also must be done to stop the war. Money to finance this conflict is also coming from the sale of fossil fuels. When we talk about new sources of energy, we’re not only saying that energy should become cleaner, we’re talking about a wholesale change in energy generation. Modern petrochemical companies are one of the most influential industries on the planet. I think that there still hasn’t been any significant progress on carbon neutrality because these companies have been making profits to the order of three billion dollars a day, every day, since the 1970s. Even back then, geologists and other specialists working in the oil industry knew very well about the consequences for the climate of fossil fuel use. In 1970, the prominent Belarussian climatologist Yury Budyko talked about it. And what did the oil companies do? They have continued to invest in extraction, and oil and gas production has increased two or three times over. Now we are in a very difficult situation where we’re facing a financial crisis. If we want to stay alive and save the planet, 90% of fossil fuel reserves shouldn’t be extracted at all, it should stay in the ground. But corporations want to use 100% of these resources. To ensure that the world can go on existing, most of these companies will have to go out of business, and this is very difficult to do. The gas and oil lobbies affirm that change is not realistic as it’s impossible to forgo fossil fuel use. However, in the situation that has developed, the choice before us is between closing down businesses and destroying the planet. We are in a critical situation and we need to think of a way out. Companies whose activities carry a risk must nationalise these risks and discuss how they conduct their businesses with society. Oil companies knew about the harm they were causing to the climate from the 1950s or 60s, but from the very start, instead of trying to change the state of things, they invested millions in propaganda against the environmentalist movement, which is why all innovation was put off for four decades. Essentially, they’re criminals. People with huge influence over society achieved their status by polluting the environment. And the reason why oil companies aren’t making the transition to solar or wind energy isn’t because they don’t know about it or can’t make use of renewables, but because this form of energy doesn’t bring comparable profits.

Is the transition to renewables at all realistic? Or at some point, will the reduced supply of oil and gas mean we’ll have to go back to using coal to heat our homes, like in the nineteenth century?

Renewable energy sources are not the same as fossil fuels. An advantage of fossil fuels is that you can burn oil and gas all day, without stopping. But when the sun goes down, the wind direction changes. I think that it’s important to understand that renewable energy requires a completely new system of energy use. For example, some factories will not be able to work all night. The model of society in which production continues 24 seven must be re-examined. The economy must change and some parts of it should disappear. The new energy system must also be based on a large number of limitations. The vertical system of energy relations, in which we have to buy energy from someone, is reminiscent of a relationship with an abusive father. Companies can continually raise prices and manipulate their monopoly of the resource. However, in a different energy system, everyone could produce energy themselves and this monopoly would no longer exist. But we can’t waste vast amounts of energy over the course of the whole day. Something will have to be sacrificed. For example, we could end the requirement for goods to be delivered instantaneously and for shops and service providers to be constantly open and available. But in the long term, these sacrifices would significantly improve our quality of life.

But how can the ecological paradigm force people who are used to having it all to limit themselves? Maybe we should go to schools and talk to the children so that the next generation can change something and not grow up feeling that they’re entitled to squander resources?

The new generation already has a different view of many things, for example, gender and sexuality. They are interested in society, but the problem is that in the West, society is atomised and individualised, everyone lives in their own world, and over the past few years, collective life has been dying. How can we personally oppose the authorities and corrupt elites which don’t think about ecology?

Eco activists know that there is an alternative; a safe future in which there is also room for pleasure. For example, I tell people that studying ecology has helped me to live a much happier life. It’s not just that our system isn’t working in an ecological sense, it’s also ineffective from the perspective of human happiness. It’s hard to call modern people happy; few of us live in harmony with ourselves and society. An ecological future is one in which people can live and work with dignity, without self-exploitation and without being constantly depressed and stressed. People are happy when they feel that they are part of something, whether that’s at work or because they’re in love. Connections are what hold us together, and ecology also teaches us to develop and maintain healthy relationships in their various aspects.

What do you make of the new British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s unwillingness to take part in the COP27 climate summit which begins on November 6th?

We are in the middle of an immediate, global, catastrophic crisis which threatens the fabric of the world in which we live. Not considering climate change to be a priority at this stage is a delusion.