“An extremely difficult generation of young people to work with”, “Snowflakes” and “Slackers” are just some of the unflattering ways employers describe the Zoomer Generation, born from the end of the 1990s to the start of the 2010s. Zoomers are starting to enter the job market where they are driving their older colleagues to distraction with their tendency to put mental well-being before careers and salaries, and readiness to quit jobs at the drop of a hat minutes after starting work. As the personality types of young job-seekers change and AI develops apace, employers’ requirements are also evolving. OECD statistics show that by next year, Zoomers will make up a third of both the world population and the workforce of OECD countries. Katia Shubert, an entrepreneur, careers advisor, and specialist in apprenticeships and recruitment for international companies, talked to Kommersant UK about the professions soon to be in demand and how Zoomers and the generation to follow them will have to adapt to the labour market.

Now all eyes are on the so-called Zoomers, Generation Z, who’re finishing school and starting to appear on the job market. There’s a lot of media chatter saying they are very self-protective and they don’t particularly want to overwork. What do you think of this generation?

I love young people dearly. I’ve been working in the recruitment of young people for 20 years now, so a lot of my time was taken up dealing with the previous ‘terrible’ generation, the Millennials. Everyone used to gripe about them as well, saying they didn’t know anything, they couldn’t do anything and they weren’t ready to work, but look, now they’re doing great! A lot of surveys and research have been done into Zoomers. It’s true a survey of employers and job-seekers by the Indeed website showed 93% of Zoomers have failed to turn up to a job interview at least once and they really don’t want to sit in an office from nine to five. On the other hand, a Fiverr survey showed that 70% of them would either like to work freelance or be self-employed. For me this is a positive sign; they have this agency and they want to be responsible for themselves, although this attitude is also caused by difficulties on the labour market. The urge to work independently may also be because Zoomers value good rapport with their bosses and research by LSE and Protiviti suggests many don’t feel they have this. It’s hard for this new generation to adjust to their employers. However, judging by the amount of research into them, companies want to learn how to work with Generation Z.

Is it true that Zoomers often quit their jobs?

An awful lot of Zoomers leave jobs within two years of being hired. It’s a great problem for companies recruiting younger workers. They invest heavily in apprenticeship programmes, organise internal training courses and appoint mentors. This means quite high-level workers spend their time helping new recruits rather than on their own duties. If these recruits then leave, then the significant sums spent on advertising, selection and training are wasted. So of course employers talk about this a lot, it’s painful for them. But I’d like to stress that in any generation, it’s important to see the individuals. It’s true that seven out of eight teenagers who I talk to as a careers consultant say they wouldn’t like to work nine to five. But my job is to bring them back down to earth. “So, you want to earn well and have a high-flying career in banking? Then you’ll have to work hard; this job requires long working hours, it’s stressful and risk-taking is unavoidable". There are quite a lot of motivated teenagers with a healthy degree of ambition and a readiness to get on. My sample isn’t large, but I hear many teens say they want to open their own business or do an office job whilst also running their own projects. Research on Generation Z suggests this may give them more control over their careers.

How important is it now for the young to receive a higher education? Many say Zoomers are choosing to work instead.

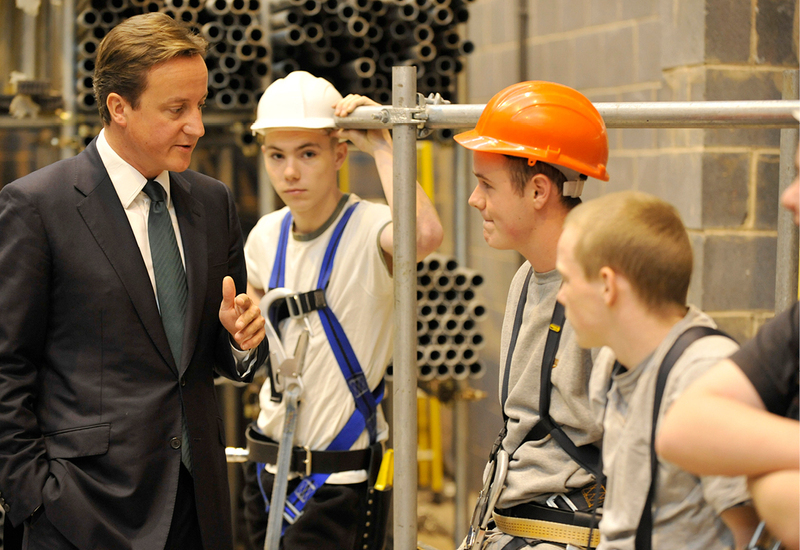

Yes, this is an intriguing phenomenon. Just recently I wrote about a 16% rise in enrollment on hands-on vocational courses at US colleges. According to a report in the Wall Street Journal, young Americans have decided it’s pointless spending vast sums on studying at university when you can make a good career and earn well from trades such as building, plumbing and so on. I haven’t seen similar studies from Britain however and, so far, I don’t see young people here turning away from university and going to college en masse. Still, it’s true only a third of Britons believe that a university degree is necessary for success. As for the trades, everyone knows a locksmith earns a lot in Britain and there aren’t many of them. Anyone who’s ever tried to find one knows what I mean. It seems it’s hard for many parents to accept this idea. “What do you mean, my lad should tighten screws? Let him study history and become a professor, or at the very least a history teacher” But so what if someone wants to tighten screws? I’ve worked with a teenager who was very interested in that line of work and he had a clear plan to train as a plumber and then open his own business. If he acts on his plan, he’s got every chance of earning well and being in demand. One thing I like in Britain is how respectful people are of those who earn through their own labour, physical or otherwise. Skilled labourers with only a college education can forge successful careers.

Apprenticeship programmes allowing school-leavers to begin work directly whilst also studying at a college or university are becoming popular. Might they be the ideal option for those who fear they won’t make the grade at university?

It’s not all that straightforward. To be admitted onto a degree-level apprenticeship, they must pass a rigorous selection process, almost as demanding as for paid work. They do the same interviews assessing their skills and abilities. Apprenticeships aren’t an easier, second-class option for weaker students. The inverse is true; getting onto a high-powered apprenticeship programme is often harder than being admitted to a mid-range university. Apprenticeships are an expensive pleasure for employers, representing a long-term investment, so selection is strict. Incidentally, the state subsidises these programmes and for several years in a row now there have been complaints that businesses and universities are making insufficient use of the allotted funding.

In-work training programmes are very popular as people understand that although they have to study for longer, they draw a salary which, however modest, means no student debt and a positive experience of work overall. Currently, more and more courses are being added which were not previously offered as apprenticeship programmes. Auditing is one example; now you can become an auditor at one of the Big Four companies through a paid apprenticeship. Similar courses have also been proposed in medicine, although many are sceptical; there are good reasons why medics spend six years at medical school, as they carry great responsibility. Paid internships are also widespread in engineering-related spheres.

Zoomers are very concerned about environmental questions such as global warming. For example, they may even refuse to work at a company which is lax about recycling its waste. Might specialists in environmental issues and sustainable development be in greater demand in the next few years?

All companies follow ESG standards (Environmental, Social and Governance) and charge their professionals to uphold them. There are requirements for hydrocarbon-free energy development plans, but I wouldn’t say it will be as hot a topic for large numbers of Zoomers as big data, cloud computing and AI.

So are professions in these areas the ones to watch?

Something might change before today’s 13 and 14-year-olds are ready to choose a university or profession. But overall, everything connected to technology, robotics, big data, cybersecurity and so on will remain in demand. According to the Times Top 100 Graduate Employers rating, in 2024, the largest number of vacancies advertised were in three areas; finance and auditing, business and management and IT. Demand for professions in healthcare and education is traditionally high.

As for changes in the labour market, AI is greatly increasing uncertainty. Even five or six years ago, it seemed far-fetched that robots might replace workers in the creative industries, rather than just drivers and those doing repetitive tasks such as accountants. Now it seems that robots can drive cars, of course, but complications and the cost of restructuring infrastructure won’t allow large-scale replacement of human drivers by robots in the near term. Physical labour is safe (so far). On the other hand, AI is developing faster and faster and will take away the standardised tasks currently performed by mid and entry-level office workers.

What professions and tasks are we talking about?

Let’s take chatbots, for instance. There used to be call centres with real people, but increasingly, they’re being replaced by chatbots. Other examples include processing documents, standard interactions with clients, writing texts and preparing presentations. Programs using AI are already partially replacing lawyers’ assistants in legal matters such as drafting documents, compiling data on court cases etc. AI is starting to take work from web designers, leaving less for the professionals who used to help clients build websites on software like WordPress and Tilda. Of course, AI-produced sites need to be tidied up, but the standard is already impressive and it keeps on getting better. At the same time, AI will create new jobs. One of the largest growth areas for vacancies is the search for professionals who can use AI to solve complex tasks for various companies. For example, some companies process large volumes of data and part of this work needs to be optimised using AI. Companies need people to come and solve these difficult tasks as none of their current staff know how to do this.

How easy is it these days for recent school leavers and graduates to kickstart their careers? There is much talk of those with psychology PhDs having to work as teaching assistants.

This varies widely depending on the profession, as there are areas which are hard to get into, such as medicine. Psychology is a field with more flexibility, but there is a whole range of professions where a master's degree isn’t enough to begin work and further study is needed, which costs money and requires many hours of supervision. I’ve seen studies suggesting psychology is one of the most popular fields for graduates. They think being a psychologist is great; you can help people and you don’t particularly need to study maths or physics. But if you look a little deeper, it’s not so simple. There are far more psychology graduates than attractive, well-paid vacancies for them. The areas where hiring remains strong are finance, banking, fintech and IT, although over the last two or three years the market has become much more difficult in these sectors as well. Everything related to technology and engineering is in high demand and consequently, so are engineering, maths and economics graduates.

Being in Britain on a student visa is clearly a hindrance when looking for a job or internship here. But the competition is fierce for everybody, even students and graduates with British citizenship or residency. As a consultant, the selection of young professionals is one area I help companies with.

First of all, graduation year is an important factor on the market. Essentially, they’re currently hiring the graduates of 2025 and 2024. Many recruitment programmes for young professionals are closed to those who graduated five years ago. After the CVs have been selected, candidates go through various tests, usually online. These are for critical thinking, teamwork, complex problem solving etc. Next is either video interviewing, where they have to record their answers as video messages, or the first round of face-to-face interviews. After that, successful candidates usually progress to a round called the Assessment Centre. This is the grand finale for the very strongest candidates; they have to solve a case study together and the interviewers watch how they carry themselves with the other applicants. As I devised and implemented these Assessment Centres myself, I have a good grasp of how it all works. When I advise teens and students, it's essential to discuss the skills they will need to pass this selection process and how they can develop them.

What do employers look at when choosing young professionals?

The most important thing for employers of course, is soft skills, whether they are recruiting recent graduates or experienced professionals. Much research has shown that employers perceive a lack of teamwork, communication and problem-solving skills in candidates. A degree from a leading university is no guarantee of a successful career in itself; those without soft skills will lose out. I urge the 13 and 14-year-olds I work with to remember that, while they can brush up their maths with a good tutor, they can't acquire strong leadership or communication skills in three months. This isn’t given sufficient attention at schools. One place where these skills are developed is at summer camps and drama lessons where young people put on plays independently, as well as in team games and volunteering. All of this requires time, which children have in short supply. Our starting point is that today’s generation of teenagers and younger workers are likely to change professions at least five times over their careers. So one of the most important skills is an aptitude for lifelong learning and re-training.

How often will it be necessary to change professions and how easy will it be to retrain?

There’s no schedule saying you have to change profession every ten years. We just don’t know how professional life will be transformed in 10-15 years. We don’t know how significant AI’s impact on our work will be. It’s important not to stand still. You have to look around, understand what new tasks are appearing in your profession and not be afraid to learn new things. So it’s very important now to help children to develop personal traits such as curiosity, an urge to look around and also resilience, stubbornness and determination to go further even if something hasn’t worked out.

Given the situation on the labour market is constantly changing, at what age should we confront a child or teen with the question “What would you like to be when you grow up?”

I usually work with teenagers from 13 and up. At this age, the brain is already working a little differently and they’re starting to look around them, so you can talk about these things. Naturally, when working with 13-year-olds, you have to approach things differently than with 16-year-olds. But this doesn't mean 13-year-olds say: “Why do I need to bother about that? I’m just a teenager; don’t ask me to do anything!”. Sometimes the parents of pre-teens come to me because they feel their kids are clued-up, self-aware and have the right outlook, but these are exceptional cases.

What else is important to say about age? In British schools, as in those of many countries, important decisions must be taken at certain times; in Britain, this includes GCSE exams, and the selection of subjects for A-level or International Baccalaureate, if the school offers that option. The choice of subject at A-level must be linked to your future studies and profession, as different university courses require different subjects and you just won’t be able to get onto the right course if you haven't passed the necessary A-level.

It’s important to have career guidance well in advance; the teenager should have the time to study the options and think things through. It can be very stressful when parents and children come to me in a panic a fortnight before the deadline to choose a course.

In 2020, the OECD conducted research into the professions school leavers in Europe were choosing. It turned out that half of the respondents were choosing from the list of the ten most obvious professions; doctors, teachers, police officers, engineers etc, as they simply had very little idea what other careers were possible. The problem is that schools don’t teach professional skills, instead, they give specific knowledge about physics, maths, chemistry and history and it’s not clear how to apply this to their furniture professional lives. This is precisely the gap I’m trying to fill by combining the work of a careers consultant with that of a marketer and HR specialist. My main concern is making sure the adolescents and young adults make their own considered decisions, rather than simply acting on my advice or on the basis of their results in some magical test. I always try to give the teenagers I work with a rod and not a fish, so I don’t just recommend careers, I teach them how to understand the labour market and their own strong points for themselves.