Food and energy prices in Britain have been growing for ten years in a row. However, recent economic circumstances, brought on by inflation and a multitude of other factors, have hit the wallets of the inhabitants of this island particularly hard. Last year, the British government promised to provide much needed-financial assistance, but, from the beginning of 2023, the volume of state support has started to fall, and banks have been allowed to raise their interest rates. Starting from April, people have been paying substantially more for housing and utilities.

In tandem with this, according to research by Barclays Bank, consumer credit card expenses rose by 4% in the year from March 2022 to March 2023, despite inflation surpassing 10% early in this period and remaining high for the rest of the year. This relatively small growth in expenditure may be due to the public tightening their belts in response to the cost of living crisis. Nevertheless, prices are continuing to rise and people are not always willing to compromise with their regular consumer habits. Since last December, an additional factor has been the strikes called by public sector workers demanding wage increases to match inflation.

A few days ago, the chief economist of the Bank of England, Huw Pill made a shocking and scandalous assertion which made headlines in The Telegraph: the British need to accept that they are poorer. While it’s impossible to disagree with him, as existing salaries cannot support the previous standard of living, the original English phrase sounds more acerbic and cynical than its Russian translation. It’s reminiscent of former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev’s “There’s no money, but you hang on in there”, which became a meme. To make it worse, Pill blames the British themselves for their poverty; he sees the situation as provoked by people’s unwillingness to forego their usual spending habits. At the same time, Pill stresses that everyone has experienced a fall in living standards, (himself included, it would seem).

The situation on this island looks worse than in other Western European countries, especially when considering that London is one of the most expensive cities in this part of the world and that all over this country prices were already quite high. Living in Britain has never been cheap, but previously this largely applied to the service sector, transport and housing, while a shopping basket of groceries remained quite affordable.

Growing energy costs have caused landlords of pubs, the main sanctuaries of social life in Britain, to increasingly talk of the unprofitability of their businesses. The cost of a glass of wine in drinking establishments is comparable to the price of a bottle of wine in a shop. According to the Daily Mail, more than a thousand public houses closed in Britain during 2022. Twice as many were forced to shut their doors due to the pandemic. The Guardian wrote that restaurants with previously inexpensive Italian food are facing particular difficulties. Due to price growth, these establishments are experiencing problems with their basic ingredients; tomatoes, pasta and flour. The Federazione Italiana Cuochi UK (FIC UK), a chefs’ association, reports that over the last year, the price of tomatoes has risen from £5 to £20 a case.

As well as increases in prices for vegetables, cheese and eggs, the British have been struck by shortages of a range of items. Eggs are sometimes hard to seek out and the choice of cheese and tomatoes has been significantly reduced. Chocolate, bread, fruit, grains, and meat have all become more expensive and on supermarket shelves replacements for meat are becoming more and more common. According to the Met Office, we can expect a scorching summer, which could lead to the loss of harvests and increase the number of foodstuffs in short supply.

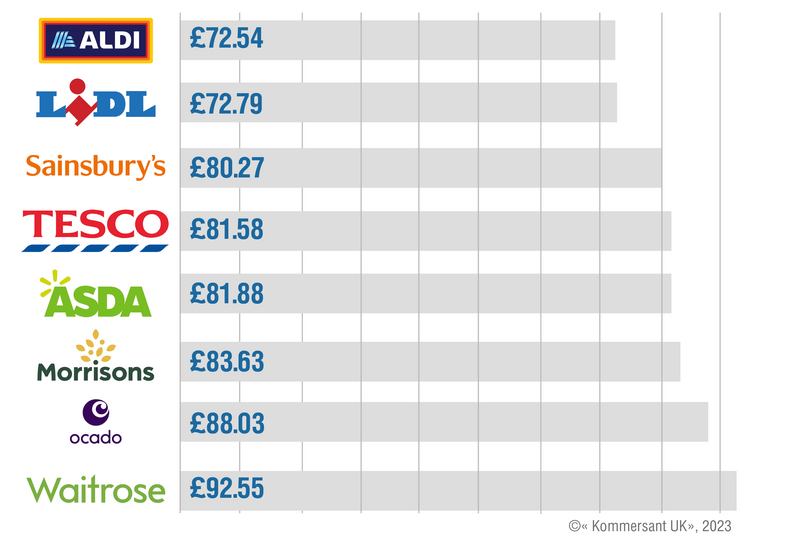

In this situation, consumers must become much more selective. On social media, the topic of which supermarket is the cheapest is subject to furious debate. According to the market research site Statista, “the big four” supermarket chains - Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Asda and Morrisons hold 73% per cent of the UK market while the discounters Aldi and Lidl have 8% of the market between them. Waitrose's organic foods are 15–60% more expensive than typical rates.

The Which? platform has set straight which of these supermarkets has been the best at holding back price increases. On comparison of 41 items from an average shopping basket, (bread, cooking oil, crisps, cheese, detergents, pet food, drinks, eggs, milk and so on), the cheapest supermarket in March 2023 turned out to be Aldi (£72.53) and the most expensive was Waitrose (£92.55) Lidl came a close second (£72.79) and Sainsbury’s was third (£80.27).

Research has also shown that in June 2022, the price of a set of 156 items was £336.89 in Asda, and £385.27 in Waitrose. In March 2023, for a different set of 137 items, the prices were £343.91 in Asda and £385.74 in Waitrose. Clearly, the results of this research cannot be called exhaustive, but even when looking at different aspects separately, the growth in prices is alarming. In 2019, the price gap for the same basket of goods between Sainsbury’s, which was the cheapest supermarket at the time, and the reliably expensive Waitrose, was only half its current size.

The BBC has made an interesting observation. They calculated that the cost of an ordinary sandwich consisting of two slices of bread, a piece of cheddar cheese and a little butter, had grown by 40 pence in the last year, which is an increase of more than 37%. The journalists affirm that there are several reasons for this; climate change, the war in Ukraine and the consequences of avian and swine flu.

Kommersant UK has conducted a poll of its readers to find out how the growth in prices has affected their living standards and how their typical shopping basket has changed.

Linda, 35, lives alone with her daughter. Her monthly income is £4,000: I work a lot. I rent and since April, I’ve been paying £150 more. The gas and electricity bills bring tears to my eyes, even though we don’t spend much time at home. Expenses for my daughter haven’t grown, although even in previous years they made up the lion’s share of the budget, which is because it’s impossible to bring up a child alone without going to babysitters and child carers for help. I used to buy groceries at a small Waitrose on the way home, and we spent £100 on average (including wine), at the weekends we often went somewhere and ate in restaurants. On getting the bills for March, I decided to cut down on trips and eating out and my typical shopping basket started to cost £150-£170. Usually, each week, we buy two steaks, salmon, a chicken, calf liver, mincemeat, crab sticks, four packs of salad, the usual vegetables for soup, aubergines, coconut milk, cow’s milk, sour cream, two bottles of kefir, frozen croissants, muesli, coffee, orange juice, chocolate, fruit, two bottles of good wine and some little things for my daughter. Now I’m thinking of getting a Tesco club card and making my purchases online; then it’ll be easier to see what I’m spending.

Anna, 43, marketing director, lives with her husband and two children, her family’s joint monthly income is £9,000:

The price of shopping trips has drastically changed. I’ve been going to Waitrose for my weekly shop for ten years, and it always used to cost me £120, including meat and fish for four. Now I pay £180-£200 for the same food. If we have guests, the sum increases to £220-£250. This has been extremely noticeable since last autumn. Electricity is the same; our bills have doubled. We have a big house and we’re now paying £3,000-£4,000 a month. When I see the bill, it makes my hair stand on end. I am still living within my budget and I can afford everything we need, but I’m starting to look at prices, cut my expenses and forgo luxuries.

Inga, 34, an accountant, lives with her husband and three children. Their household income is £3,000:

We’ve pretty much even stopped going to the pub. My husband and I take it in turns to go out; he goes somewhere once a month, and so do I. We look at bills to see how much we’ve eaten and drunk. To be honest, it’s an odd, unsettling feeling. I do the shopping. There is a big Tesco’s next to our house. Our usual big groceries shop every fortnight or so used to cost £180. I buy pasta, grains, tinned foods, vegetables for soups, frozen meat, chicken liver and the most basic fruits and vegetables. We’ve almost stopped buying fish. When I saw that an ordinary mackerel had almost tripled in price, I thought it would be better to get another pack of minced meat. Now our same big shop costs about £220.

Kira, 49, a school teacher who lives alone, her monthly income is £2,450:

My children have grown up and they live independently. I help them from time to time, but I can't compare it with my previous expenses for their education and upkeep. To be honest, when they moved out, it freed up a lot of money. For a couple of years, I felt like a millionaire. I’m joking, of course, but I started to make regular visits to theatres, go out for meals with friends and to travel. I went to a beautician and a good dentist. Covid, of course, interrupted all of that, but there was a sense of having something to look forward to. Now that’s gone. I’m still living in a big house, and I’m now paying enormous bills for it. It’s good that I don't have a mortgage anymore. That’s made life significant;y easier. But, to be honest, I think I’ll have to rent out this house and move to a small two-bedroom flat closer to London. I’m in my second spring now. I stopped counting how much I paid for groceries when my youngest son left home; I don’t eat much and I never go over £40 a week on principle. But the rising prices become quite noticeable when all four of my children come to see me with their other halves. At Easter, for instance, I bought food for a four-day family gathering. It seems I spent £300 in Lidl, £200 in Aldi and £150 in Waitrose. I don’t remember ever spending so much previously, not even last Christmas. In my favourite pub, I used to pay £12-£14 for a couple of glasses of wine, but now it’s £22-£24. I can see how the prices have gone up for my favourite foods and drinks; wine and caviar have gone up, Peking Duck in Sainsbury’s used to cost £6, and now it’s almost £10. As I’m alone, I’m still just about managing to maintain my usual lifestyle, but I can already feel the pressure; it’s getting harder to save up for holidays or to help my children.

Alexander Smotrov, director of the Russian and Eastern European Department of Global Counsel, an international consultancy:

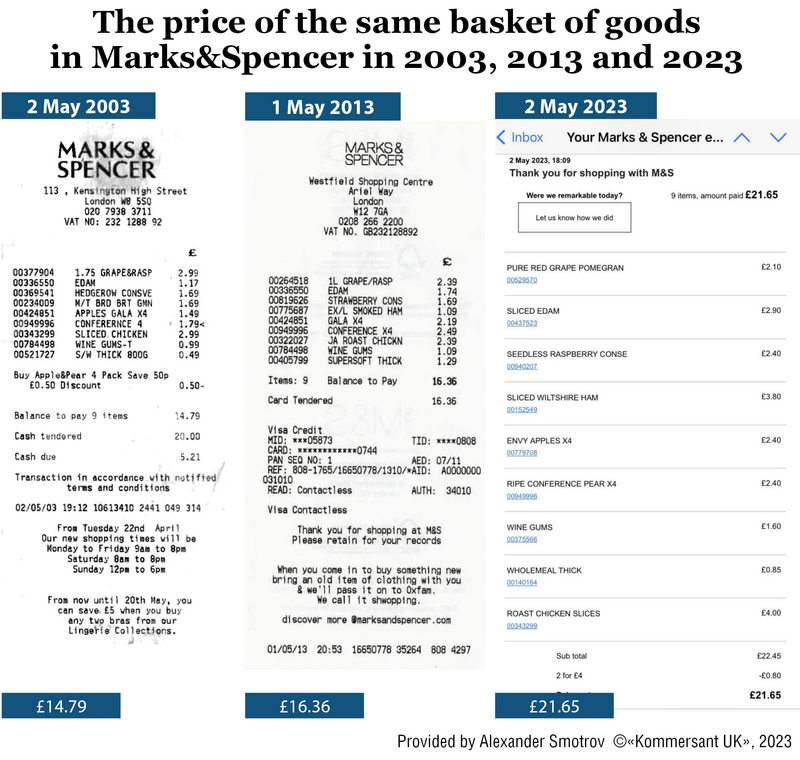

The start of May this year marked the twentieth anniversary of my life in London, and, as is traditional, I made a “sample purchase” in a supermarket. The same set of goods (bread, fruit, two kinds of cold meat, cheese, juice, jam and sweets) cost £14,79 in 2003, £16.36 in 2013 (an increase of 10%) and £21.65 in 2023 (an increase of 32% in ten years). Of course, prices for groceries have risen perceptibly, but this isn’t just a British phenomenon. I think that inflation will force us to reconsider when we eat fruit and vegetables, as in season they’re tastier and cheaper. Why pay outrageous sums in winter for imported strawberries, peaches which taste of carrots and wooden tomatoes? Another indicator of retail inflation over the last 20 years of my life in Britain has been the price of beer. There was a time when we were horrified that the price of a pint of ale had reached £3, but now we pay £5, and every time, it somehow seems awkward. For many years, one bastion against inflation has been £1 bunches of daffodils in spring, but most likely this will soon fall too…