Steve Garrett is a social entrepreneur (the founder of Cardiff Riverside Market), writer and poet who volunteers for the British branch of the Alternatives to Violence Project (AVP). He is part of a group of AVP volunteers who talk to prisoners to help them find ways to become non-violent after being released.

Kommersant UK has spoken to Steve Garrett about the main goals of his volunteer work, the lack of prison funding in the UK and the general nature of men's violence.

Steve, when did the AVP project initially begin?

It began in 1975 when inmates at Green Haven Prison, a maximum security facility in New York State, asked local Quakers to help them teach incarcerated youths how to resolve conflicts nonviolently. While working in these prisons, the need was recognised to help inmates find ways to manage their emotions and reduce violence. Just being in prison presents challenges, but the constant risk of being attacked exacerbates the situation. Therefore, they developed the project to understand peace and violence and transition away from violence towards peace. From the start, the project emphasised practicality rather than philosophical or theoretical discussion of aspects of non-violence. They focused on understanding the problem’s root causes and identifying techniques to help individuals gain better control over their emotions. Since its start in the 70s, the AVP project has expanded, and it is now present in over 50 countries worldwide. Not all groups work solely in prisons however, we also work in local communities in the UK.

Normally one group consists of 12-16 prisoners and three volunteers from AVP. Workshops in prisons normally last for three days, with sessions being five hours each.

I've been doing work in two prisons for around a year now and I've been doing similar sessions in communities for 8 years. So far, I've worked in Berwyn Prison in North Wales (it’s the largest prison in the UK) and in one prison in Costa Rica; I was invited there. I do speak Spanish, so I could communicate with the prisoners there very well. In October this year, I ran workshops in Cardiff prisons as it's my home town. I'm also going as part of an AVP group to South Africa next year, hopefully.

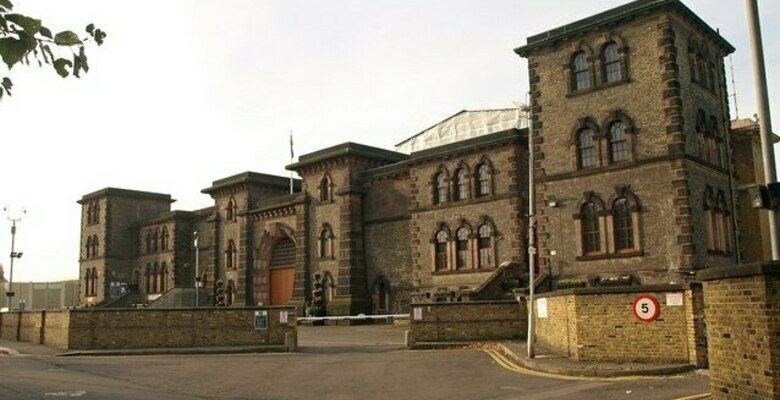

Given the recent news about Daniel Khalife's prison escape (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-66743634), what do you think, is it easy to escape from prisons in the UK?

I’m not sure if it's easy to escape from UK Prisons, but I do know that some of them are in a very bad state which surely makes escapes easier. In fact, they urgently need government investment. It seems that the main reason that Daniel Khalife was able to escape so easily is that around a third of the prison officers didn't show up for work that day because of sickness. This is an excellent example of how badly underfunded prisons are, like many public services at present.

How do your conversations with prisoners usually start?

We ask them how they are feeling; not about being in prison, but about being in the workshop, whether they’re optimistic, anxious or curious. This is the beginning of the process of connecting with them at the most basic level. Simple questions about how they feel help them to be more confident, and relaxed and they help them to feel heard and respected. If they say they feel anxious, we say we don't blame them. The important thing is that they should feel we are listening to them and that we are really paying them attention when they tell us about their feelings. We ask other men to listen to each other, as this is an important skill which many of them have never learned. We say “Everybody needs a good listening to”, especially in prisons...

Once they realise that we are there to support them, not to judge or criticise them and that we are volunteers who also want to learn from each other, in my experience, their attitude then becomes more positive.

We don’t just talk during our workshops, there are many activities like role-playing and other participation exercises but also sometimes we play fun children’s games with prisoners to create a soothing atmosphere, it makes them feel more comfortable and eases their emotional state. The main thing we say is that the workshops are experimental and practical, not theoretical. We believe this is the best way to help the participants learn the most they can from them and remember what they have learned

What is the main aim of this work with prisoners?

The most important aspect, I do believe, is to provide individuals in prisons with the opportunity to learn and grow. It is certainly crucial to acknowledge and accept that individuals who have committed crimes need to be held accountable, but it is also important to understand the underlying factors that may have contributed to their actions.

Many of these men have experienced abuse in their childhood and lived in dangerous environments, without the chance to learn better ways of behaving. Given their backgrounds, when they are released from prison one day, many of them may re-offend and come back to prison. By working with these inmates showing them respect for who they are as human beings and helping them understand the consequences of their actions, we can provide them with the tools they need to manage their emotions, build self-confidence, and ultimately reduce the likelihood of their reoffending.

So all these efforts benefit not only the individuals in prisons but also our society as a whole. When these individuals are given the opportunity to learn more about themselves and develop the necessary skills to manage their feelings, they are more likely to reintegrate into society, make a useful contribution and avoid committing further crimes.

Of course, prisons are not created as places where people are supposed to feel good. But in this country, they are too full and they're struggling with limited funding, especially in terms of mental health support and teaching the skills that can be useful in the outside world… It's not that prison administrators don't care about this, they simply don't have the resources.

However, we also know that a high proportion of men who have been in prison will return there after being released because they didn’t really learn anything during their time in jail. All they learn there is more about how to commit crimes. They pick this up while interacting with other prisoners. I believe that prison can be a place where men can learn about themselves, about the lives they’ve been leading and about how they can make better choices in their lives. As far as I'm concerned, men in prisons are not bad men. They are men who have made mistakes in their lives and they may have done bad and harmful things, but I believe everyone, including all men, of course, is inherently good. If a man goes astray, what he really needs is help and support to change himself for the better, not only for his own sake but also for the sake of anyone who comes into contact with him for the rest of his life.

You've mentioned that British prisons have limited resources from the government to support the prisoners... how are they dealing with this?

Overall, prisons in the UK are doing their best with limited resources. They run educational programmes and as volunteers, we can deliver activities at a very low cost for the prisons while providing real benefits to both the inmates and society. Counselling services in prisons are typically provided by the prison administration, but, in practice, this does not often happen. It's not that the prison staff don't understand the need for education and support for prisoners, but they have limited resources to offer. Some prisons bring in people like us from outside to provide activities like art or creative education.

The predominant public perception of prisons is that they are places where people are punished, but statistics show that this approach isn't effective. A high proportion of men who have been in prison end up reoffending and returning there. I believe that unless we provide support and help for men to change their behaviour, prison is just a way to temporarily contain people that won't make society any safer.

If we return to the story of Khalife's escape which you asked me about, I do think that more funding is needed to support the kind of educational work that we do. We must support prisoners to help them make better choices and rebuild their lives when they are released. We should make it easier for them to avoid getting involved in crime and coming back 'inside'. This investment is morally right, it helps to make the community safer and it will also save the Prison Service money in the long run!

Do you usually know what crimes the prisoners you talk to have committed?

No. It is very important to mention that when we work with a group of prisoners, we don't ask them why they are there or what crimes they have committed. It's irrelevant to our sessions and how we work with them. We approach them primarily as individuals, as human beings, and treat them with respect. In the beginning, we always emphasise that everyone in the room is both a teacher and a learner and that we are all equal.

Still, if, in conversation, they want to reveal the crime they have committed, that's fine. We also reveal a bit about ourselves to the group of prisoners (and the three of us volunteers), but not too much. I'm not shy about sharing that when I was a young man, I spent a short time in prison myself. Sometimes they also ask us if we have been in prison and I share my experience with them because I hope it helps them feel more relaxed with me and understand that I’m not judging them as human beings.

Is the fact that you've had this experience of being in prison yourself one of the reasons why you've decided to do this?

My personal experience is a big part of why I volunteer, but I also acknowledge that I have been fortunate. My family supported me while I was at university. I’ve also had other help and support from my family and society. When I compare myself to these men who haven't been given a chance, I realise that what they’ve done in their lives is not completely their fault. They are not to blame for growing up in a difficult environment, they just need help to change.

The idea is to treat each of them with respect. We all have a basic need to feel respected and a part of society. This gives them a chance to escape their previous patterns of behaviour.

Are prisoners required to visit the workshops or are they only optional?

They are certainly not forced to come to our workshops, it is always their choice to participate. This means that the men who attend are there because they genuinely want to change. If they don't want to change, there's no point in working with them. Many men in prison want to avoid reoffending in the future and they are eager to change. Sometimes they are unsure if they actually can, and we help them with that.

They are very open when it comes to talking about their lives. I was surprised by how willing they were to share their experiences. They don't talk with pride about being involved in violence; they simply explain what they did. Sometimes they mention that they had to use violence to defend themselves or a friend. Our goal is to teach them that there are better ways to defend themselves. Even if they believe someone deserves to be hurt, if they end up back in prison, they are the ones paying the price.

What motivates prisoners to be willing to spend hours on your workshops?

When we ask them if anyone wants to come back to prison after being released, no one raises their hand. So we tell them that in the workshops they can practise and learn skills that will hopefully help them never return to prison again. This is a strong motivation for them, much stronger than us telling them how they should behave or be better men. By not returning to prison, they will be better people as they won't be committing crimes.

The starting point is always to help them achieve their goal of never being readmitted to prison by teaching them how to manage their emotions and find better ways of dealing with their anger. This enables them to make better choices, no matter how other people might behave. They realise that being a violent man isn’t the same as being a strong man or being worthy of respect as a human being.

What are your thoughts about the nature of violence in men?

If you look at all kinds of violence, it primarily comes from men, and often against men too! It's important to recognise that there needs to be more support for men because they are not inherently bad or violent. Obviously, men can become violent under certain circumstances or situations, but they all have the capacity to be non-violent and learn how to live in the world and interact with others in a non-violent way. There is much evidence to support this.

When I try to understand the roots of violence, I believe that it is rooted in fear. Men become violent when they feel threatened in some way. That's why an important part of the work we do is helping these guys develop self-esteem and self-confidence. Many of them don't feel good about themselves on the inside. That's why they lash out or behave aggressively.

Has your first year of experience working with prisoners taught you anything?

This has been a great learning experience for me. For example, when I was in San Jose in Costa Rica, when the group came in, they had a lot of tattoos of skulls and skeletons all over their bodies and quite a few on their faces. If I were to meet some of them on the streets, I might feel afraid because they look threatening. However, as soon as they realised we were there to help, and that we were treating them with concern and respect, they were completely fine. They were friendly to us and treated us respectfully.

It made me realise that the way someone looks doesn't necessarily reflect who they are as a person. When you meet someone new you don’t know anything about them, and it's my experience that even if men look threatening, they often aren't, unless they themselves feel threatened. Some prisoners may not value themselves, and no one else has ever valued them or told them to value themselves, so their acting or looking aggressive is a form of self-protection. So, a really important foundation of non-violence work is for all men to feel valued as human beings and to learn to value themselves. Once you value yourself, you can value others too. If you don't respect yourself, you can't respect others either. And if you treat others respectfully, there is more chance that they will respect you back. And if they don’t, that’s their problem, but not a reason to be aggressive with them.