Among the events of the past year, a special mention should go to the great “migration of peoples” experienced without exception by all the countries of Europe. Across the continent, the number of newly-arrived Russian-speaking migrants has exceeded a million. To a greater or lesser degree, practically all of them have encountered problems adapting to their new cultural environment. Psychologists advise that those who want to make a sudden change to their lives, by, for instance, quitting smoking, should do so in stable conditions, and not combine it with a change of job or other important life event. All changes are stressful for the psyche, but if everything else is calm, then you’ll cope with this stress relatively easily. However, moving to another country will plunge many aspects of your life into the depths of chaos and uncertainty. Unfortunately, this makes stress and severe travails almost inevitable.

To find out more, watch Kommersant UK’s webinar with the sociolinguist Elena Mccaffrey where she discusses the five main mistakes made by emigrants. [Russian only]

All the joys of culture shock

Maybe you haven’t thought about it, but in your homeland, your development and growth were a search for opportunities grounded in the surrounding community. Everything from your knowledge and skills to your social connections and place in the professional environment, as well as your domestic habits and how you organise your day, make up the innumerable network of interdependencies that hold your psyche together. On moving to another country, you carefully extract yourself from your familiar environment and naively think that eventually, your worldview, made of interlocking jigsaw pieces, will fit into the new reality. When it turns out these pieces won’t slot into the puzzle of the new culture, you feel shocked. This shock is intensified when you realise your pieces, rather than just being a poor fit, are almost completely incompatible, with unexpected implications for wide-ranging aspects of your life.

So you experience culture shock, which is not just a pretty expression. This is a scientific term which describes someone’s mental state when they encounter a foreign culture. The concept of culture shock was coined in 1954 by the Canadian anthropologist Kalervo Oberg, who used it to describe the physical and psycho-emotional state experienced on losing your habitual models of social interaction. Amongst the symptoms of culture shock, Oberg included heightened alarm, fears for your own personal safety and that of close family, disrupted sleep and appetite, more frequent hand washing, heightened concern about the cleanliness of water and the quality of food, paranoia, feelings of helplessness and fear of going out and interacting with the foreign culture. Other researchers have found that culture shock can include a wide range of psychosomatic disorders, from heartburn and muscle pain to sudden flare-ups of chronic illnesses.

In other words, culture shock is a conflict between the individual’s internal expectations about both themselves and the new society, and what happens in reality. Even if their new surroundings are not particularly hostile, the migrant may perceive them as oppressive and stifling.

Following the U-curve

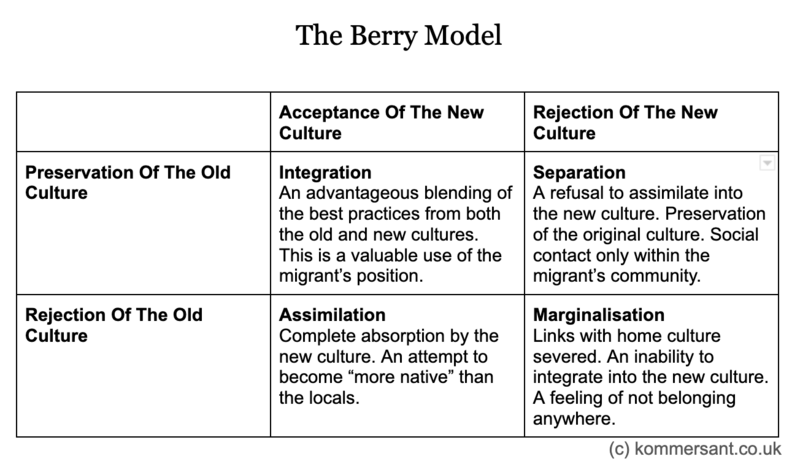

In 1970, the American anthropologist Philipp Bock proposed four strategies for resolving conflicts caused by culture shock. Later, the American psychologist John Berry developed them into a binary model. This proposes that migrants may either accept or reject the new culture, while simultaneously either retaining their original culture or rejecting it.

Source: https://open.maricopa.edu/culturepsychology/chapter/berrys-model-of-acculturation/

Extensive research has shown that the best strategy is integration, combining the best aspects of both the old and new cultures. This is pretty much the only course which is beneficial to mental health. Managing to fit into the new society while not turning away from the aspects of the old culture that can be useful in the new setting enables the migrant to take advantage of their position with access to two cultures. However, the path of integration is onerous.

It is believed that adaptation to a new culture occurs according to a U-shaped curve, a model described by the Norwegian sociologist Sverre Lysgaard. Upon finding themselves in the new setting, people are first inspired by the new culture, have novel impressions and experience euphoria. This is the honeymoon phase. As soon as people encounter real difficulties and understand the degree to which the new culture is different to what they are used to, they enter a stage of crisis. This is characterised by fierce criticism of the new culture and a perception that understanding or loving it is impossible. The problems snowball, and the person is in grave need of a psychologist. This second stage is the bottom of the U-curve. The third stage is an acceptance that reality cannot be changed and a realisation that they must accept their new situation and make adjustments. The individual begins to solve problems and understand how the host society works. They make useful acquaintances and begin to feel that they are experts on the topic of integration, although this may be far from the case. Later, when the actions and practices initiated and developed during the third phase have borne their fruit, the migrant finds their place in the new culture and can make plans for the future. Rather than being driven by the bare need to survive, the aim is now for self-realisation in the fourth and final stage of adaptation.

Various interpretations of these stages exist, but the salient point is that they happen to virtually every emigrant. It is impossible to predict how long it will take to go through each stage since this depends solely on you and your personal circumstances. Many people get stuck in different stages for months or even years. One thing is important; to understand that going through this process is inevitable. So, maintain your self-confidence and keep going at your own speed. Others have succeeded, and so will you. The key complication is individual variability in the nature of the challenges and how easily you cope with them. You won’t be able to predict how greatly you will suffer from everyday problems, how difficult the process will be for your mental health or whether homesickness will force you to return to your homeland. You will only begin to understand these things as you experience the different stages of this journey. Innumerable factors affect the length and difficulty of the process of adaptation, including your age, sex and mental flexibility as well as your resilience, level of education and the extent of the difference between the culture you grew up in and the one you now find yourself in. In any case, if you work yourself successively through the U-curve, time will be on your side, and one day, you will suddenly realise that you have been enriched by your new experiences and that you now have a firmer footing in the new society.

Untangling the knot

Stress and panic may be caused by any of a huge number of small difficulties, each of which could act as a detonator for the delicate mental state of an immigrant who has recently arrived in a new country. It’s not so easy to untangle this knot, although anyone can manage to unpick one or two threads. Below we have described the main problems which every emigrant has to face. How can this list be used?

First of all, by no means attempt to follow all of this advice at once. Remember that you are experiencing significant strain coping with the stress and worry of unexpected situations. This is why your effectiveness and productivity are markedly lower than what you were accustomed to. Choose any of the points set out below, preferably the one which currently seems the most pressing, and follow the instructions.

Secondly, set yourself goals, even tiny ones, which in different circumstances would seem derisory. These little victories will be small steps towards making a happy and comfortable life for yourself in your new surroundings. Even just being able to laugh at yourself and a situation that was previously driving you mad is a colossal victory. Big things start with little steps, and making enough tiny steps in the right direction will ensure that great changes are just around the corner.

Thirdly, imagine that it is a game. A quest you want to complete, although you’re still not quite sure how. If you have ever played a computer game you’ll remember how you’d struggle through a level, blasting away the regular baddies, only to meet the boss, who was too much for you. So you went through that level again and again, trying to kill the final foe in some different way or to approach him from a better vantage point. You gave your all and didn’t give in. The thrill of the challenge kept you hooked and made finishing the level easier. The good news is that in this challenge, the boss doesn’t exist. The main enemy is a tangled ball of questions and difficulties. By solving these, one by one, you’ll defeat the boss.

1. The language barrier

What is it? The inability to talk in the local language, communicate with local people, take part in local life or receive the information you need. Often, this is associated with a fear of initiating or maintaining social contact.

What to do? First of all, you must understand that fear makes mountains out of molehills. In fact, even if you don’t know the language, in critical situations there are many ways of making yourself understood. Secondly, at the very least, an online translator will help. Thirdly, studying the language will greatly help you to overcome the language barrier. It’s easiest to start at the level of small talk; before going to the shop, learn two or three phrases and use them. Gradually introduce new phrases, and then you won’t have to think about each separate word, you’ll have ready-made constructions.

2. Different customs and traditions

What are they? The person does not fit the cultural norms of the new setting and the norms of the new setting do not fit the migrant’s expectations. This manifests itself in unconscious violations of unwritten rules and customs. Fear of seeming inadequate leads to a lack of the confidence needed to make meaningful social interactions.

What to do? Study the social rules of the new country. Fortunately, you can start doing this right now. Take advantage of what you can learn from other people’s mistakes. There is plenty of material available about adaptation to local norms, including what your compatriots who have made the move to the same country have posted in online discussions. This is a very important aspect, since ignorance of the language may be forgivable, but there is less tolerance for the breaking of social codes.

3. Lack of social support

What is it? The absence of support and understanding from family and friends and insufficient opportunities to socialise and discuss problems. A shortage of tactile contact.

What to do? Ideally, find a psychotherapist, best of all one who specialises in the problems of immigrants. With professional help, it’s easier to overcome this problem and many others that come with it. Equally importantly, you will have a loyal ally during a difficult time. You also need to both establish regular contact with people who are dear to you back home and expand your social circle in the new country. There’s no guarantee that your new acquaintances will give you any support, but successfully developing a social life is sure to lift your morale.

4. Self-image issues

What are they? The loss of the usual cultural references used for self-appraisal leads to a need to reconsider your self-image. This is often accompanied by an objective assessment of the loss of status, role in society, property and social circle.

What to do? First of all, accept that no one can move to another country without losing something in one area of their life or another. Secondly, accept yourself as someone who is living through a new experience. When blasting off to space and feeling the G-force, Gagarin, the first cosmonaut, is unlikely to have felt like a hero. He is more likely to have felt like an insignificant grain of sand in the face of the infinite cosmos. The third thing is to keep a diary. Reserve one part of it for free expression, and use these pages to pour out all the things that are making you stressed, let it all go, up to and including obscenities directed at the local inhabitants. Complete the second part following the same principle, but here, concentrate on the positive. Be sure to include all your victories, even the most insignificant ones. The diary will give you resilience and help you to keep going.

5. Different value systems

What is it? A mismatch between your usual priorities and those of people in the new country. This is expressed as an inability to understand people’s motives and actions, why popular topics of conversation are so important and local attitudes to various phenomena.

What to do? Socialise with other emigrants and discuss what you don’t understand about the new country. It may seem that the best solution is to befriend a native who could be your guide to local rules and customs. This really is a good idea that should be put into practice, but for a local person, many things that you find surprising are perfectly unremarkable and self-explanatory, while for immigrants they stick out straight away. Watching local TV and music videos can also help; as a rule, the key concepts which are important to local society will become clear quite quickly.

6. Misunderstanding cultural norms and etiquette

What is it? Having no knowledge of the accepted written and unwritten rules and codes of behaviour can lead to you breaking them repeatedly. This may affect all areas; the rules of polite conversation, the volume of your voice, the distance between people during social interaction and even the understanding of time, as when is considered appropriate to invite round guests and how late it is acceptable to be may vary. These issues are fraught with danger as outsiders may provoke conflicts without even realising.

What to do? Meet the locals and ask them. Also, watch how they talk and interact amongst themselves. Try to go for walks, observe the locals and see how they behave with each other. When you get home, practice acting like them. Don’t be afraid to ham it up. The sooner your exaggerated acting becomes natural behaviour, the fewer questions and funny looks you’ll get.

7. Problems of social integration

What are they? Difficulties establishing social contact and taking part in local life. Anxiety may make the migrant reluctant to start up conversions with local people and fear rejection by them. The sense of alienation and personal worthlessness risks becoming overpowering.

What to do? Socialise, socialise and socialise again. Some people, such as shop assistants, police officers, receptionists, and your children’s teachers, are obliged to interact with you because of their jobs. Try to engage them in conversations which go a little beyond the matter at hand. You’re not likely to make any friends this way (although who knows), but you’ll gain practice interacting with the natives, which will boost your self-confidence. Common interests are another good way to make new acquaintances. This is how young mothers, dog owners and volunteers meet each other.

8. A mismatch of expectations about gender roles

What is it? A difference between the gender roles familiar to the migrant and customs and behaviour patterns in the new country. This may lead to involuntary violations of the accepted rules of the host society, or an avoidance of relationships with the opposite sex out of a fear of being misunderstood. This is an area where the risks of running into unpleasant consequences such as conflicts or even legal proceedings are quite high.

What to do? Study the question and talk to other emigrants, especially those who are in relationships with local people; they are an invaluable source of knowledge. Observe how couples behave too. In a cafe, or on the street, you may see by chance what happens at the bouquet and chocolates stage of relationships. In shops, or on public transport, you can watch established couples and in parks or toy shops, you can observe couples with children. Take heed of everything you manage to see; who initiates conversations and how this is done, the tone of the discussion, who looks after the children, who pays, who goes through a door first, who helps whom and so on.

9. Differences in child-raising methods and norms

What is it? Unawareness of the accepted rules and norms governing childcare in the host society. A projection of the migrant’s own expectations about parental roles into the new setting. This is also a rather delicate question since unplanned interaction with other people’s children may lead to conflict, and establishing interaction patterns with our own children which are imported from back home may lead to a fine or even more serious consequences.

What to do? If you have no children, you could just avoid interacting with them altogether. Fortunately, most of the time you’ll likely have nothing to do with them. However, if either you or your newfound friends have children, find a discussion group for young, recently arrived parents as they quickly gain knowledge of what is considered appropriate when dealing with children in a new country. Having taken note of the questions people ask each other, you should understand the key differences fairly quickly.

10. Differing expectations about lifestyle and behaviour

What is it? Your habitual lifestyle or the new habits you acquire as an immigrant may contradict the social expectations of the new country. Many things may cause irritation, from your appearance and style of dress to your snacking habits on public transport or the volume at which you sigh. Due to thin walls, your daily routine may also affect your neighbours. As a result, at best you risk getting funny looks, at worst, you may cause conflict.

What to do? First of all, reconcile yourself to the old adage “When in Rome, do as the Romans do”. In your new setting, your choice of lifestyle and behaviour is limited. Secondly, decide which of your inclinations and habits you are ready to forego. Then, either live as you are accustomed to and put up with the disapproving attitude from the locals, a choice fraught with conflict and other serious consequences, or reconsider and identify the points where you are breaking local norms. By the way, if your appearance and lifestyle haven’t stopped you from making friends among the natives, your new acquaintances can help you do this.

Five stages of adaptation to a new cultural setting:

• Contact. The first meeting with the new culture. New experiences cause excitement and euphoria. Searches for similarities with the home culture. Differences are viewed positively as the migrant searches for confirmation that they have made the right decision.

• Disintegration. Confusion and disorientation as the migrant realises the full extent of the difference between the old and new cultures. Stress and frustration grow. In contact with members of the new culture the migrant experiences alienation and a lack of self-confidence. Confusion over identity mounts.

• Reintegration. A strong rejection of the new culture. Defensively, the individual regresses into their old culture, seeking relationships within it. Personal difficulties are projected onto the second culture. At this stage, the individual may choose to return to their homeland

• Autonomy. The acquisition of skills and increased cultural sensitivity enable greater interaction with the new culture. The previous defensiveness is abandoned and the migrant is ready to enter into new relationships. A realisation that survival is possible without the cues and cultural props of the old culture.

• Independence. The final stage is the acquisition of confidence in the new culture. The individual’s thoughts, attitudes and behaviours are independent in the new cultural context. Self-realisation leads the migrant to a sense of their distinct identity with access to the patterns and values of both cultures. Tolerance of multiculturalism.

The Six Aspects of Culture Shock:

• Strain resulting from the effort of psychological adaptation to the new culture;

• A sense of loss or deprivation caused by the loss of friends, wider social circle, possessions, status and role in society;

• Total or partial rejection of or by the new culture. Feelings of alienation.

• Confusion about social norms, roles, and how to interact. A loss of self-identity;

• Unexpected anxiety, disgust, or indignation caused by cultural differences between the old and new cultures;

• Feelings of inadequacy and helplessness as a result of not coping well in the new environment. A fear that full self-realisation may not be possible.