Steven Keogh was a police officer with London's Metropolitan Police for 30 years, over half of which he spent as a Scotland Yard detective, investigating both murder and terrorism. After retiring from the force, he wrote two books about investigating murders: How Scotland Yard Really Catches Killers and Jack the Ripper.

Kommersant UK spoke to him about his work at Scotland Yard and the factors that need to be taken into account during a criminal investigation. We learnt his opinions on recent notorious murders in the UK.

How did your police career begin and why did you choose this path?

It wasn't something I had wanted to do as a child; it developed later on. After leaving school, I started training to become an accountant. However, that was really boring... My workplace was near the Old Bailey, London's central criminal court for serious crimes. Witnessing the comings and goings of prisoners, surrounded by a bustling police presence, seemed far more exciting than the accounting job I was preparing to do. So, at the age of 20, I decided to join the police. My career led me to six years in uniform before I became a detective. I spent three years investigating terrorism before being promoted to detective sergeant. I spent three more years working on local serious crime before going on to focus on murder, where I stayed until the end of my career. In total, I served in the force for 30 years.The two oldest of my four children now work in the police force as well. I didn't influence their career choices, but I've always maintained a positive outlook. I enjoyed my own policing career. Many people, police officers included, often moan about the job, but I never did.

What was the hiring process like at Scotland Yard at the time you joined?

To become a detective, initially, you had to work in uniform for at least two years. Then you could choose to follow the route of a detective. This entailed moving to a second unit, investigating crimes related to drugs, burglary, or robbery, before eventually becoming a detective at a local police station. Afterwards, you could apply for a more central role, which is what I did. The hiring process has changed since then; now you can become a detective without doing time in uniform. Personally, I don't agree with this change, as I believe recruits should first gain experience in how to deal with people effectively. They also need to learn how to make arrests in uniform before becoming detectives

What specific personality traits make someone suitable for a career in the British police, in your opinion?

Being a police officer is about dealing with the public, so it’s crucial to be good with people. Some of the worst policemen I've met were those who could not even talk to their colleagues. If you can't communicate well, it makes the job difficult. One of the most important aspects of being a police officer is the ability to communicate. You deal with violent individuals, those experiencing trauma, and people in distress, and you might need to reprimand others, so being able to adapt how you communicate in different situations is vital. Being good with people is probably the most valuable skill for a police officer.

How strong does one's mental resilience need to be for police work, especially in the Homicide Investigation Department?

The point is you don't go straight into dealing with murders. When you join the police you start to deal with things like car accidents, assaults, and attending incidents of sudden death. (In the UK, when this happens the police need to be called to ensure there's nothing suspicious). All these things build up your resilience for when it comes to dealing with murders. The hardest part for me was dealing with the trauma of families and grieving relatives who had lost children or partners. I became used to seeing dead bodies and blood.

What do you think about British police officers not carrying weapons?

I fully agree with that. If you look at the number of police officers who are murdered in the USA compared to the number in England, there's a significant difference. Many officers are killed in America and around the world, and their firearms do not protect them. I personally wouldn't want to carry a gun. When necessary, we need our officers to have them, but they aren’t needed routinely.

It is widely known that, after their release, a lot of offenders end up back in prison (the charity AVP is trying to help them avoid this). How often during your career have you noticed that criminals have repeated their crimes, and what kind of crimes did they commit?

In my 30 years of work in the Metropolitan Police, I dealt with hundreds, if not thousands of criminals. The vast majority of them were repeat offenders. It would be rare to encounter someone who has committed a serious crime who doesn’t have a previous conviction, although not all have served prison sentences, as our criminal justice system tends to deal with first-time offenders in other ways. As for the crimes they committed, they tended to be either theft-related (burglary or robbery etc), drugs or violence. There would be a majority with drug convictions, be that supply or possession. Drugs are intrinsically associated with crime, in this country and abroad.

And what was the most horrific crime you've ever dealt with?

The 7/7 bombings were terrible. There were four bombs on the London Underground train and a bus, with no concern for the people who would be killed and injured.

Also, I think the most horrific crimes I ever dealt with personally were the murders of children. Those are the hardest crimes for me to understand. Crimes committed by individuals like Ian Brady, Myra Hindley or Peter Tobin. Those crimes, anything involving a child, are the worst.

Since the Sarah Everard case and Wayne Couzens's arrest, public trust in the police has unfortunately been significantly undermined. What are your thoughts on this situation?

Everything the police do, from stopping speeding cars to dealing with terrorists, is about protecting people and society. When incidents like what Couzens did occur and police officers are known to commit crimes, especially against women, it makes me sad. The police should be the ones people turn to when they are scared. I find it all upsetting and it makes me sad... I know it's not the entire police force's fault, the individuals involved are to blame. It takes some time to regain trust, and hopefully, it will be restored one day.

Could anything have been done to prevent these cases? They were perpetrated by those in positions of authority who are supposed to protect the public. Were they impossible to foresee?

There are a few things. First, during the initial stages of recruitment, there needs to be thorough vetting. Once individuals are in the police, their colleagues and supervisors should be vigilant for signs that something is not right. If concerns arise, there should be a mechanism in place to make it possible to report colleagues and a general understanding among officers that this is the right thing to do. We are not quite there yet. When someone reports a colleague, they should receive a lot of support because it's not an easy thing to do. So, if there are reports (either criminal or just general concerns), they need to be investigated properly. I believe the vetting, reporting of colleagues, and investigating of allegations haven't been as robust as they should have been over the years, and improvements are necessary.

Two of your books are available in paper; Jack the Ripper and How Scotland Yard Really Catches Killers. You also have one more out as an eBook, Understanding Why People Kill. Who is their intended audience?

The first two books are specifically about the procedures surrounding murder investigations. I wouldn't say they cater to a specific group. Some true crime enthusiasts might not appreciate them because they prefer real insights into a particular murder. For me, I've written more about how the process is carried out, how we investigate, and what the truth is. How Scotland Yard Really Catches Killers takes the reader from the crime scene all the way through to the trial in court, explaining the steps of a murder investigation. It describes how murder investigations are conducted, discussing specific aspects such as forensics or CCTV in real-life cases. The book guides the reader through these steps, from the crime scene to the court. It is for people who want to know precisely how murder is investigated; journalists, TV professionals working with murders, and still, to some extent, true crime enthusiasts. In the case of the eBook, I do public speaking about investigations and crime-related topics, so I've published it to help an audience understand what I'm talking about.

In your opinion, what's the most important aspect of criminal investigation: analytical skills, experience, professionalism, or simple intuition?

For me, the two most important skills are communication and attention to detail. Communication is key because a lot of information in murder investigations comes from people. When dealing with witnesses, they may not necessarily tell you what is important; they tell you what they want to tell you. Communication is a critical skill for a detective. Attention to detail is crucial, especially in murder investigations, to ensure all procedures are correctly followed and protocols are adhered to. Lawyers can exploit any mistakes in the investigation, potentially allowing a murderer to escape conviction.

What about gut feelings?

While having a gut feeling is essential, it needs to be handled carefully because it can be wrong. If you have a feeling, you must investigate why you have it and not be blindly led by it. For instance, if you feel someone is a killer based on intuition, that's just one aspect; you must have evidence to support it.

So, can body language be misinterpreted?

Body language can be misleading. Body language experts may claim to know when a person is lying, but what they are identifying are signs of stress. Stress can come from various factors, such as being interviewed by a police officer, being on TV, or simply being asked questions. While body language may indicate stress, it cannot definitively identify lying.

What about polygraph tests, can we trust them? By the way, are they still used in the UK?

We don't use them in criminal investigations in the UK, I think for good reason. They can't be 100% relied on and I believe they could cause more harm than good.

In your experience, how helpful are forensic psychologists in police investigations?

We rarely used forensic psychologists; we used profiling occasionally, mainly for specific murders with a sexual element, or when there was a link between murders that suggested a possible serial killer. In most murder cases, we did not seek their assistance. Psychologists or psychiatrists would be more commonly involved when someone charged with murder claims to be suffering from mental illness at the time of the crime.

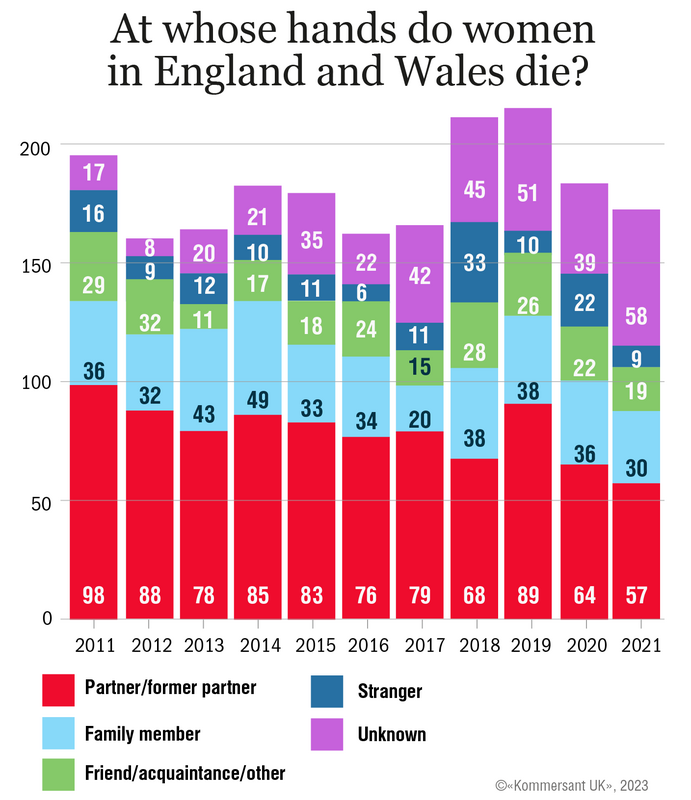

According to the yearly ONS statistics on Female Homicide Victims 2011-2021, women are at a higher risk of violence from partners or relatives than from strangers on the street...

In around 50% of cases, these women were killed by their current or ex-partners, which is quite frightening. It's a terrible statistic, and as a society, we need to be better at protecting women and girls from violence. Progress has been made; for example, coercive control has become a crime in recent years. Previously, if someone hadn't physically assaulted their partner, it was challenging to charge them with anything. When it comes to violence and murders within relationships, it often stems from a history of abuse; financial, sexual, and psychological. Recognition of this has improved, but there's still a long way to go to protect women in our society.

According to the same statistics, the number of unresolved murders in the UK has significantly increased since 2011 (there were 17 that year, compared to 58 in 2021). What could be the reason for this?

In 2012, the government started making cuts to the police, reducing the number of officers and cutting budgets. When you cut down police numbers, crime tends to increase. For example, when I first started investigating murders in 2009, there were 29 murder investigation teams in London. Now there are 20, essentially a 33% reduction. Each team has to handle more murders, meaning less time per investigation. Time and resources are needed to conduct thorough investigations and solve murders. Having less time means fewer chances of solving the cases. It's a sad reflection of what has happened across the police. The statistics for unsolved rapes, robberies, burglaries, and murders have all increased.

In your eBook, Understanding Why People Kill, you break down motives for murders into three categories (Push of emotion, Pull of emotion, and Gain). Are there murders that don't fit into these three categories, and if so, in what cases?

An exception is people who are seriously mentally ill and have psychotic episodes, hear voices, or experience hallucinations. These individuals may not know what they are doing, and it's challenging to attribute a clear motive to their actions.

To which of these three categories would you assign to Lucy Letby, the nurse who killed infants?

I would categorise Lucy Letby's actions as the ‘Pull of emotion’. It appears she derived some emotional release from harming those babies. The initial act provided her with a certain thrill or satisfaction, and she may have wanted to replicate that feeling by continuing to harm infants. This pattern aligns with the behaviour of serial killers who seek enjoyment from their actions and aim to recreate the initial experience. Human behaviour often involves seeking activities that provide a thrill and repeating them to recapture that feeling. For instance, if we try a rollercoaster and enjoy it, we want to go on it again and then we might want to try a bigger one to experience more excitement. Lucy Letby might have started with something as simple as making a baby cry and eventually escalated to the point of causing their deaths.

She was sent to prison rather than a psychiatric hospital. Does that mean she was in a rational mental state when she committed the crimes?

It doesn't indicate she didn't have any mental issues, but she would have understood what she was doing was wrong. Even in prison, individuals can receive psychiatric evaluations and treatment for underlying mental health conditions. A prison sentence implies that, at the time of the crimes, she was deemed aware of her actions. It doesn't rule out the presence of psychological issues or personality disorders, which can still be addressed within the prison system.

Do you think she might be a psychopath?

I suppose Lucy Letby may have underlying mental health issues, but to say she is an actual psychopath requires a professional diagnosis. I am not a doctor so I can’t say for sure.

Speaking of psychopathy, in our talk last year with an NHS doctor, he mentioned an interesting study suggesting more psychopaths are found among CEOs than among criminals in prisons. How often did you encounter individuals with psychopathic traits among murderers?

It is funny to say, but the honest answer is we do not know. Assessing individuals for psychopathic traits is not a common practice during murder investigations. These assessments typically occur when a person charged with murder claims a ‘defect of the mind’, asserting that a mental illness affected their judgement at the time of the crime. Being a psychopath is not considered a defence in criminal cases. No one can just say “I committed this crime, but I'm a psychopath, so I'm not guilty of murder”.

The reality is that very few murderers are actually assessed to see whether or not they are psychopaths or have some sort of personality disorder, it just does not happen.

Given the recent news of Levi Bellfield’s false confessions, how often do criminals admit to crimes they didn't commit, and what motivates them?

It is really rare. The reason might be that they were seeking attention. If someone confesses, it means nothing. The police may believe them, but still, evidence is needed to support the confession. You would not convict someone just based on their word. Even if you were to confess to a murder, there would be aspects of the crime police are aware of that are not public knowledge. Only those involved in the murder, or its investigation, would know about them. During my career, I encountered a couple of instances of someone trying to confess to something they did not commit. All you have to do is ask them a little bit of detail about the crime that only the police or someone present at the time of the murder could know. If they can't describe that, then it is a good indication they did not actually commit the crime. In the case of Levi Bellfield, I don't know him, but from the outside looking in, I think he just wanted attention.

Do you agree with the statement that all murderers experienced violence in childhood, so society in some ways holds responsibility for all crimes?

I don't agree with that at all. Many people who suffered violence and sexual abuse in childhood don't commit crimes. To me, the only person who holds much responsibility for a crime is the person who committed it. You can't shift the guilt onto society; it's only a personal choice. These people knew it was wrong to commit the crime but they still did it. Society has some issues, but you can't take responsibility for someone choosing their path through life; it was their decision.